Volume 3, Issue 4, 2025

Editorial

Reframing the Approach to Predatory Journals; Embracing a 'Non-Recommended Journal' Model

Abdullah Khalid Omer

For more than a decade, the academic publishing community has been locked in a battle against “predatory journals.” These are commonly understood as outlets that exploit the open access model by charging fees to authors without providing genuine peer review or editorial services [1]. While this campaign has been well-intentioned, its implementation has been riddled with inconsistencies and collateral damage. It is time to re-evaluate our approach—and a promising alternative has recently been proposed.

At the 18th Meeting of the European Association of Science Editors (EASE), Kakamad et al. introduced the concept of the Non-Recommended Journal (NRJ), offering a more nuanced and constructive way to classify questionable journals. Their proposal, outlined in a poster presented at the event, acknowledges a critical truth that the current binary model overlooks: not all low-quality or problematic journals are predatory, and not all accused journals are guilty [2].

One of the core issues with the term “predatory” is its lack of a universally accepted definition. Attempts to label journals as predatory can often be subjective and based on flawed or incomplete criteria. This ambiguity has led to wrongful accusations and the potential defamation of emerging or under-resourced journals that are making genuine efforts to improve. Worse still, some well-established journals exhibit questionable practices yet avoid scrutiny simply because they don’t fit the “predatory” mold [3].

The NRJ framework reframes the discussion by focusing not on intention, but on recommendation. Rather than asking whether a journal is maliciously exploitative, the NRJ model asks whether a journal meets acceptable standards of transparency, editorial rigor, and academic integrity. Journals that do not meet these standards—whether due to deliberate misconduct or lack of infrastructure can be flagged as “non-recommended” without implying criminality or predation [2].

This shift in terminology allows for a more flexible and inclusive way to monitor journal quality. It accounts for the so-called “borderline journals,” which may not be outright deceptive but still fail to uphold scholarly standards. By avoiding the inflammatory label of “predatory,” the NRJ system reduces the risk of reputational harm while still guiding authors, reviewers, and institutions toward better publishing decisions.

Moreover, the NRJ approach invites continuous re-evaluation. Journals can move in and out of this category based on demonstrated improvements, providing a growth mindset rather than cementing stigmas. This dynamic classification also encourages more transparent criteria, ideally informed by independent watchdogs or academic associations rather than commercial blacklists.

It is time we recognize the complexity of the academic publishing ecosystem and evolve beyond the simplistic predator-prey narrative. The NRJ concept represents a practical, fair, and forward-thinking step in that direction. As the academic world continues to grapple with questions of quality, ethics, and accessibility, such innovations are not just welcome, they are essential.

Original Articles

Predictors of False-Negative Axillary FNA Among Breast Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study

Lana R. A. Pshtiwan, Sakar O. Arif, Harzal Hiwa Fatih, Masty K. Ahmed, Shaban Latif, Meer M....

Abstract

Introduction

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is commonly used to investigate lymphadenopathy of suspected metastatic origin. The current study aims to find the association between nodal characteristics and cancer-related factors with the rate of false-negative preoperative FNA.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional study included breast cancer patients with negative preoperative axillary FNA results who underwent postoperative histopathological evaluation. Data were collected from electronic medical records, including clinical, imaging, cytological, and pathological findings. Patients with incomplete records, non-axillary or inconclusive FNAs, positive preoperative FNAs, or unsampled axillae postoperatively were excluded. Key variables analyzed included lymph node size, cortical thickness, tumor grade, histological type, immunohistochemical subtype, and metastatic patterns.

Results

A total of 209 negative axillary FNA samples were analyzed, with a mean patient age of 46.13 years. Invasive ductal carcinoma was the most common diagnosis, and ER-positive tumors were the predominant subtype. Ultrasonography identified suspicious axillary nodes in 20.57% of cases. Histopathology revealed a 27.75% false-negative rate, with a negative predictive value of 78.3%. Larger lymph node size and cortical thickness exhibited lower false-negative rates, while histologic type and ER status showed significant associations with false-negative outcomes (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

The 27.75% false-negative rate of preoperative FNA remains concerning and may not be sufficiently low to justify foregoing definitive axillary staging. The current study found significant associations between false-negative FNA rates and histological subtype and ER status, the latter of which is not explicitly mentioned in the literature.

Introduction

Breast cancer represents the most commonly diagnosed malignancy among women globally. In 2020, it surpassed lung cancer to become the leading cancer diagnosis in women worldwide, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases reported [1,2]. Precise clinical staging plays a pivotal role in assessing prognosis, informing treatment strategies, and anticipating clinical outcomes in breast cancer. A critical component of staging is the evaluation of axillary lymph node involvement, as the presence or absence of metastasis in these nodes substantially influences therapeutic approaches and overall survival rates [3].

Conventional techniques, including sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), have long been the standard approaches for axillary staging in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Despite their diagnostic utility, these invasive procedures are associated with inherent risks and potential postoperative complications, notably lymphedema [1].

Axillary lymph node fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) has gained recognition as an effective method for staging breast cancer. When performed under ultrasound guidance (US-FNA), this technique allows for targeted sampling of suspicious axillary lymph nodes through a minimally invasive approach, providing a less invasive and potentially less morbid alternative to traditional methods such as SLNB and ALND [4]. This technique exhibits high diagnostic accuracy in detecting metastatic disease. Although the overall diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound-guided FNAB is well documented, the understanding of lymph node characteristics that influence the technique's sensitivity for detecting metastatic disease is limited [5]. Ewing et al. demonstrated that true-positive FNAB results were more likely in larger lymph nodes compared to false-negative results. Furthermore, true positive FNABs were associated with a higher percentage of nodal replacement by carcinoma, in contrast to false negative FNABs [6]. Establishing a precise correlation between the diagnostic sensitivity of FNAB for detecting metastatic malignancies and specific nodal characteristics remains challenging. The current study aims to establish the relationship between nodal characteristics and cancer-related factors with the false-negative FNAB rate through a retrospective analysis of data from 209 patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional study. Data were collected over two months, from November to December 2024. All participants provided informed consent, including agreement to the use of their anonymized data for publication purposes. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kscien organization (Approval No. 2025-34).

Data source

Data were obtained through a review of electronic medical records, which included demographic information, medical history, presenting complaints, preoperative imaging findings (ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography), FNA results, diagnosis, treatment approaches, and postoperative histopathological outcomes.

Eligibility criteria

The study included patients diagnosed with breast cancer who had negative axillary FNA results before surgery and underwent histopathological assessment postoperatively. Exclusion criteria included patients with incomplete medical records, FNAs not sourced from the axillary region, positive preoperative axillary FNA results, FNAs conducted outside the study center, inconclusive FNA findings, cases where the axilla was not sampled after surgery, and hemorrhagic FNA samples. The following characteristics were analyzed: lymph node size, histological cancer type, immunohistochemical subtype, cortical thickness of axillary lymph nodes, tumor grade, and metastatic patterns.

Procedure

Ultrasound-guided FNA was systematically performed, adhering to established clinical protocols. Verbal informed consent was obtained before the procedure, with the target axillary lymph nodes initially identified through palpation and subsequently confirmed using high-frequency linear ultrasound imaging (7–15 MHz transducer). Patients were positioned in supine orientation with ipsilateral arm abduction to optimize anatomical access. Following alcohol antisepsis of the procedural field, a sterile 23-gauge Chiba-type needle connected to a 10 mL syringe via a pistol-grip aspiration device was percutaneously introduced into the lymph node cortex under continuous real-time sonographic visualization. Dynamic negative pressure (5-10 mL suction) was maintained during 3-5 controlled, multidirectional needle passes within the target lesion, with vacuum release executed before needle withdrawal to minimize peripheral blood admixture. Aspirates were promptly processed by smearing on glass slides and fixing in 95% alcohol for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Post-procedural hemostasis was achieved through sustained manual compression for 3 minutes, followed by clinical monitoring for immediate complications.

Statistical analysis

The data were initially collected and recorded in a Microsoft Excel (2024) spreadsheet and subsequently imported into version 25 of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. The results were presented as frequencies, ranges, percentages, means with standard deviations, and medians. A significance level of P < 0.05 was adopted.

Results

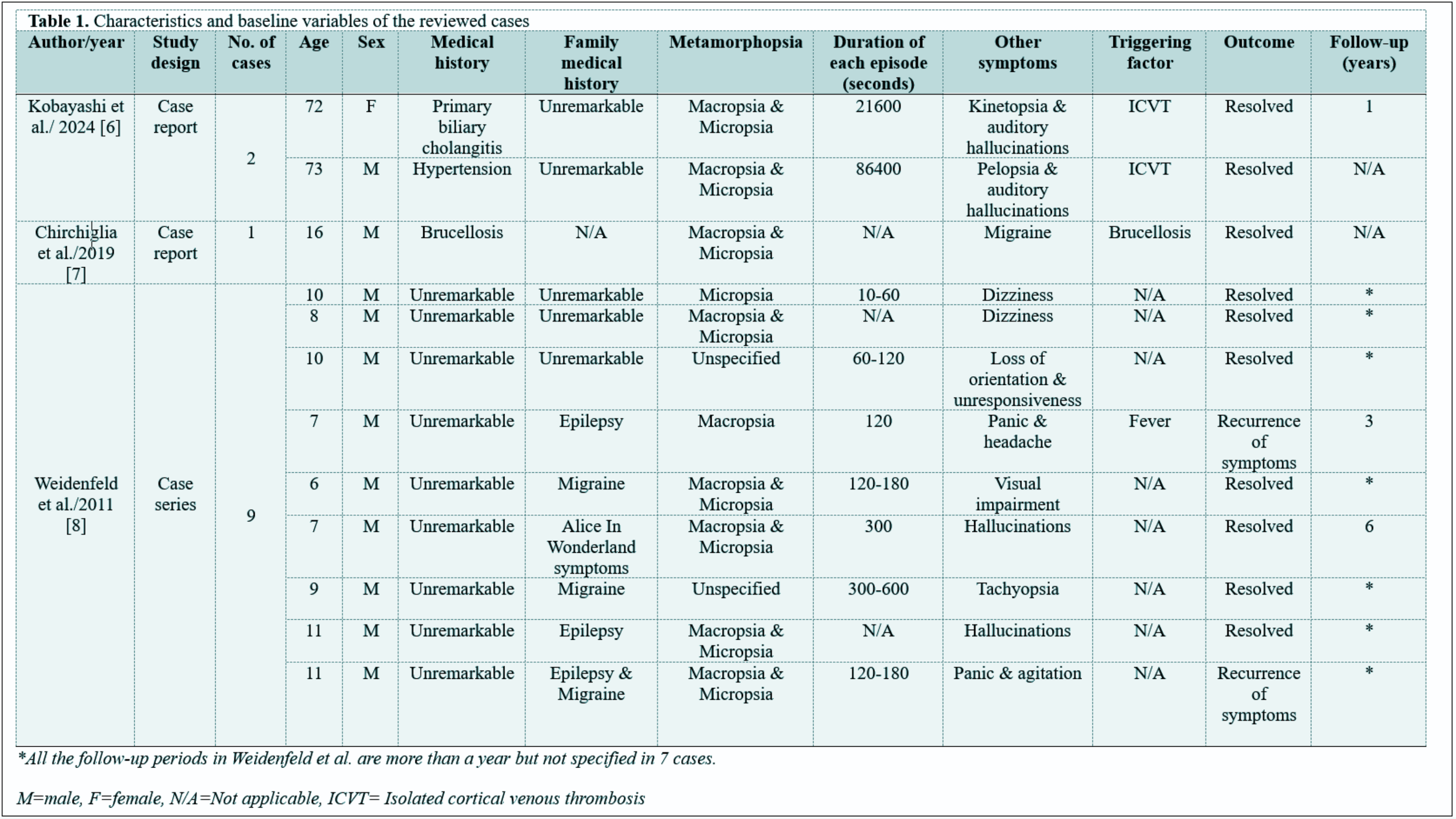

A total of 209 negative samples were included in the study. Ages ranged from 25 to 84, with a mean age of 46.13 years. A family history of cancer was reported in 70 patients (33.49%). The right breast was affected in 106 cases (50.72%). Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was the most common diagnosis (156, 74.64%). Grade II was the most abundant tumor grade (105, 50.24%). Upon immunohistochemical (IHC) examination, it was revealed that ER+ was the most common subtype of cancer (126, 60.29%) (Table 1).

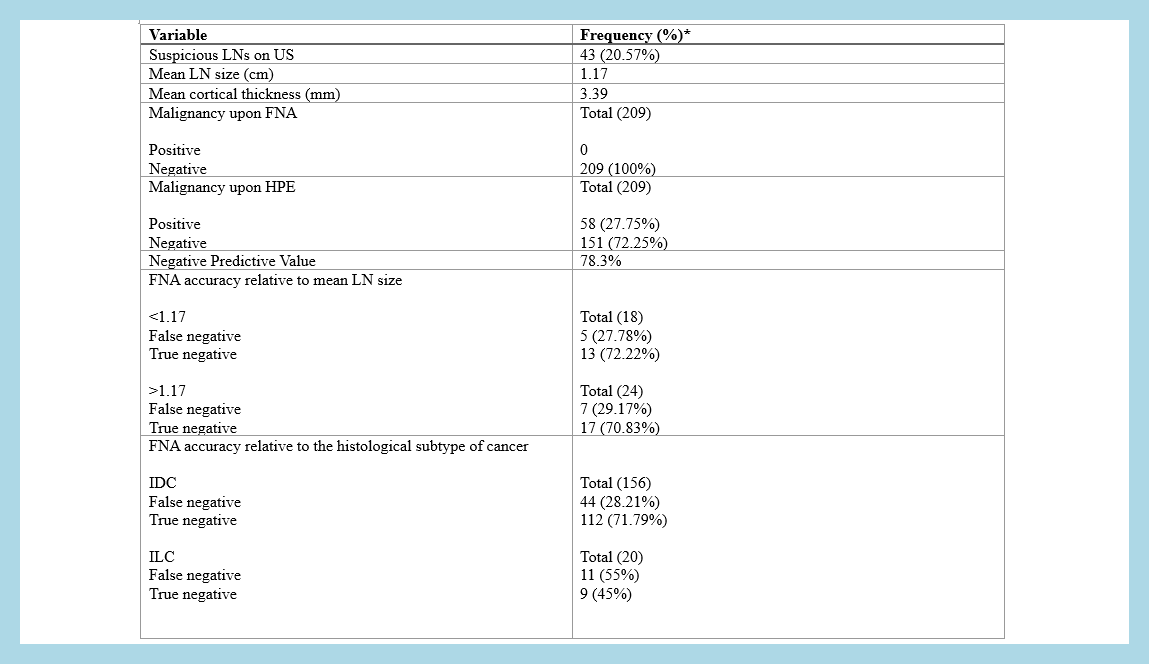

Ultrasonography of the axilla showed 43 (20.57%) suspicious nodes. The mean size of the lymph nodes was 11.7mm. Among the included samples, 58 (27.75%) were false negatives upon histopathological examination, while the true negatives were 151 (72.25%). Negative Predictive Value (NPV) was 78.3%. The rate of false negative readings decreased as the size of the lymph nodes increased above the mean size (11.7 mm), and a similar trend was also seen in cortical thickness. However, a statistically significant association wasn’t established (Table 2).

Among the analyzed characteristics, histologic cancer type and ER status were associated with false-negative readings (P-value < 0.05) (Table 3).

|

Variable |

Frequency (%) |

|

Age groups 25-34 35-44 45-54 55+ |

Total (209) 29 (13.9%) 60 (28.7%) 77 (36.8%) 43 (20.6%) |

|

Mean age ± SD |

46.13 ± 11.79 |

|

Median age |

49 (IQR=15) |

|

Family history of cancer |

70 (33.49%) |

|

Affected side Right side Left side |

Total (209) 106 (50.72%) 103 (49.28%) |

|

Diagnosis IDC DCIS ILS Others |

Total (209) 156 (74.64%) 20 (9.57%) 20 (9.57%) 13 (6.22%) |

|

Tumor grade Grade I Grade II Grade III N/A |

Total (209) 17 (8.13%) 105 (50.24%) 52 (24.88%) 35 (16.75%) |

|

Cancer subtype (IHC)* ER+ PR+ HER2+ |

126 (60.29%) 98 (46.89%) 23 (11%) |

|

IDC: Invasive ductal carcinoma, DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in situ, ILS: Invasive lobular carcinoma, N/A: Not applicable, IHC: Immunohistochemistry *More than one receptor can be positive in a single patient, hence why the percentages don't add up to 100%. |

|

|

Variable |

Frequency (%) * |

|

Suspicious LNs on US |

43 (20.57%) |

|

Mean LN size (cm) |

1.17 |

|

Mean cortical thickness (mm) |

3.39 |

|

Malignancy upon FNA Positive Negative |

Total (209) 0 209 (100%) |

|

Malignancy upon HPE Positive Negative |

Total (209) 58 (27.75%) 151 (72.25%) |

|

Negative Predictive Value |

78.3% |

|

FNA accuracy relative to mean LN size <1.17 False negative True negative >1.17 False negative True negative |

Total (18) 5 (27.78%) 13 (72.22%) Total (24) 7 (29.17%) 17 (70.83%) |

|

FNA accuracy relative to the histological subtype of cancer IDC False negative True negative

ILC False negative True negative

DCIS False negative True negative

Others False negative True negative |

Total (156) 44 (28.21%) 112 (71.79%)

Total (20) 11 (55%) 9 (45%)

Total (20) 2 (10%) 18 (90%)

Total (13) 1 (7.69%) 12 (92.31%) |

|

FNA accuracy relative to receptor status ER+ False negative True negative

PR+ False negative True negative

HER2+ False negative True negative |

Total (126) 41 (32.54%) 85 (67.46%)

Total (98) 31 (31.63%) 67 (68.37%)

Total (35) 11 (31.43%) 24 (68.57%) |

|

FNA accuracy relative to mean cortical thickness (3.39mm)

<3.39 False negative True negative

>3.39 False negative True negative |

Total (80) 24 (30%) 56 (70%)

Total (69) 20 (28.99%) 49 (71.01%) |

|

FNA accuracy relative to tumor grade

Grade I False negative True negative

Grade II False negative True negative

Grade III False negative True negative |

Total (17) 6 (35.29%) 11(64.71%)

Total (105) 35(33.33%) 70(66.67%)

Total (52) 10 (19.23%) 42 (80.77%) |

|

LN: Lymph nodes, FNA: Fine needle aspiration, US: Ultrasound, HPE: Histopathological examination, IDC: Invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC: Invasive lobular carcinoma, ER: Estrogen receptor, PR: Progesterone receptor, HER2: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *The number in parentheses represents the count of patients for whom data were available. |

|

|

Variable* |

False negative |

True negative |

P-value |

|

Lymph node size (Mean ± SD) |

1.26 ± 0.5 |

1.29 ± 0.6 |

0.969 |

|

Cancer type (N, %) IDC ILC DCIS Others |

44 (28.21%) 11 (55%) 2 (10%) 1 (7.69%) |

112 (71.79%) 9 (45%) 18 (90%) 12 (92.31%) |

0.013 |

|

Receptor status ER+ PR+ HER2+ |

41 (32.54%) 31 (31.63%) 11 (31.43%) |

85 (67.46%) 67 (68.37%) 24 (68.57%) |

0.038 0.411 0.594 |

|

Cortical thickness (Mean ± SD) |

3.54 ± 0.74 |

3.56 ± 0.92 |

0.206 |

|

Tumor grade Grade I Grade II Grade III |

6 (35.29%) 35 (33.33%) 10 (19.23%) |

11 (64.71%) 70 (66.67%) 42 (80.77%) |

0.235 |

Discussion

Recent studies have provided insights into the factors contributing to false-negative FNA results in axillary lymph node evaluation for breast cancer. Earlier research by Ewing et al. identified smaller lymph node size (<1.2 cm) as a significant factor associated with false-negative FNA findings [6]. However, in the present study, lymph node size did not show a statistically significant association with false-negative results. This may be attributed to the fact that lymph node measurements were reported in only 20% of the cases, limiting the power of the analysis. Notably, consistent with previous literature, there was a trend of decreased rate of false-negative results as lymph node size increased beyond the mean threshold of 1.17 cm. It is plausible that a significant association might have emerged had a larger proportion of cases included lymph node size data.

Few recent studies have directly compared false-negative FNA rates among IDC, ILC, and other histological subtypes, representing a notable gap in the literature. Prior work, such as Chung et al., suggested that ILC’s diffuse, discohesive growth and smaller metastatic foci may contribute to higher false-negative rates [7]. Supporting this, Sauer and Kåresen reported false-negative rates of 16% for ILC versus 6% for IDC, indicating that histological subtype may impact FNA sensitivity [8]. In the present study, a statistically significant association was found between histological subtype and false-negative FNA rates: IDC accounted for 75.86% of false negatives, ILC for 18.97%, and other types for 5.17%. It is worth mentioning that this association may be attributed to the higher prevalence of IDC compared to other cancer subtypes. Further research comparing subtype-specific FNA accuracy, particularly between IDC and ILC, is warranted to optimize preoperative axillary staging.

Regarding receptor and HER2 status, current evidence does not support a consistent association with false-negative rates of axillary FNA in breast cancer. Some studies suggest that axillary FNA sensitivity may not significantly differ by breast cancer subtype (including ER/PR/HER2 status), though negative predictive values can vary [9]. The current study found a significant association between ER-positive tumors and false-negative FNA readings. However, PR and HER2 status had no significant association with false FNA readings.

Cortical thickness is a key factor influencing the accuracy of axillary FNA. Thinner cortices (<3.5 mm) are linked to a higher risk of false-negative results, likely due to lower tumor burden and sampling difficulties [6]. Although a statistically significant association was not demonstrated, likely because only ~17% of cases reported cortical thickness, the data suggest an inverse relationship between cortical thickness and false-negative rates, consistent with existing literature. Raising the cortical thickness threshold when selecting nodes for FNA may reduce false negatives and enhance diagnostic accuracy, though this must be balanced against the need for sensitivity in specific clinical contexts.

Tumor grade, which reflects the degree of cellular differentiation and is often associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastatic potential, was not found to be significantly associated with false-negative FNA rates. This aligns with existing literature, where tumor grade has not been identified as a major predictive factor for FNA accuracy. Notably, a higher rate of false negatives was observed among lower-grade tumors. This finding is consistent with the biological behavior of such tumors, which are typically less aggressive and may present with smaller or fewer nodal metastases, making detection more challenging.

Although this study did not demonstrate a statistically significant association between false-negative FNA rates and the differentiation and is often associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastatic potential, was not found to be significantly associated with false-negative FNA rates. This aligns with existing literature, where tumor grade has not been identified as a major predictive factor for FNA accuracy. Notably, a higher rate of false negatives was observed among lower-grade tumors. This finding is consistent with the biological behavior of such tumors, which are typically less aggressive and may present with smaller or fewer nodal metastases, making detection more challenging.

Although this study did not demonstrate a statistically significant association between false-negative FNA rates and the pattern of metastasis (micrometastasis vs. macrometastasis), prior literature has identified a notable link. Iwamoto et al. reported that 25% of patients with negative FNA results were subsequently found to have micrometastases on sentinel lymph node biopsy, contributing to a false-negative rate of approximately 31.5 [10]. Similarly, Fung et al. found micrometastases in 5 out of 16 patients with false-negative FNAs, underscoring the cytological challenge in detecting smaller metastatic foci [11].

In addition to nodal and patient-related factors, human error remains a significant contributor to false-negative FNA results and may compromise the validity of data analysis. These errors include sampling issues, operator dependency, interpretive variability, and subjective clinical decision-making. Alkuwari and Auger reported that nearly all false-negative cases in their study were due to sampling errors rather than misinterpretation [12]. Although less frequent, diagnostic challenges in cytology, particularly with scant cellularity or atypical morphology, can lead to interpretive errors. Moreover, the decision to perform FNA is often based on the clinician’s subjective assessment of nodal suspiciousness, which may result in missed metastases if abnormal nodes are not sampled [13].

A key limitation of this study was the incompleteness of the collected data, with several variables lacking sufficient information. Although the results were mostly in line with the literature, with some unusual findings, it likely affected the pattern of metastasis (micrometastasis vs. macrometastasis), prior literature has identified a notable link. Iwamoto et al. reported that 25% of patients with negative FNA results were subsequently found to have micrometastases on sentinel lymph node biopsy, contributing to a false-negative rate of approximately 31.5 [10]. Similarly, Fung et al. found micrometastases in 5 out of 16 patients with false-negative FNAs, underscoring the cytological challenge in detecting smaller metastatic foci [11].

In addition to nodal and patient-related factors, human error remains a significant contributor to false-negative FNA results and may compromise the validity of data analysis. These errors include sampling issues, operator dependency, interpretive variability, and subjective clinical decision-making. Alkuwari and Auger reported that nearly all false-negative cases in their study were due to sampling errors rather than misinterpretation [12]. Although less frequent, diagnostic challenges in cytology, particularly with scant cellularity or atypical morphology, can lead to interpretive errors. Moreover, the decision to perform FNA is often based on the clinician’s subjective assessment of nodal suspiciousness, which may result in missed metastases if abnormal nodes are not sampled [13].

A key limitation of this study was the incompleteness of the collected data, with several variables lacking sufficient information. Although the results were mostly in line with the literature, with some unusual findings, it likely affected the data analysis and impacted the overall findings.

Conclusion

The 27.75% false-negative rate of preoperative FNA remains concerning and may not be sufficiently low to justify foregoing definitive axillary staging. The current study found significant associations between false-negative FNA rates and histological subtype and ER status, the latter of which is not explicitly mentioned in the literature.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Patients provided consent to participate in the study and to authorize the publication of any related data.

Source of Funding: Smart Health Tower.

Role of Funder: The funder remained independent, refraining from involvement in data collection, analysis, or result formulation, ensuring unbiased research free from external influence.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: LRAP and AMA were major contributors to the study's conception and to the literature search for related studies. MMA, MKA, and HHF were involved in the literature review, study design, and writing of the manuscript. RMA, HAY, SL, SOA, and BOH were involved in the literature review, the study's design, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the table processing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. BOH and MMA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Use of AI: ChatGPT-3.5 was used to assist in language editing and improving the clarity of the manuscript. All content was reviewed and verified by the authors. Authors are fully responsible for the entire content of their manuscript.

Data availability statement: Not applicable

Echinococcus granulosus in Environmental Samples: A Cross-Sectional Molecular Study

Thamr O. Mohammed, Shvan L. Ezzat, Hawnaz S. Abdullah, Sangar J. Qadir, Aga K. Hamad, Sahar A....

Abstract

Introduction

Echinococcosis, caused by tapeworms of the Echinococcus genus, remains a significant zoonotic disease globally. The disease is particularly prevalent in areas with extensive livestock farming. Humans primarily acquire infection through consumption of contaminated food or water, often from environmental contamination by definitive host feces. This study aimed to detect the presence of E. granulosus DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) in water and vegetable samples collected from Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraq.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraq, in April 2025. Water and vegetable samples were collected from both urban and rural areas. DNA extraction was performed from all samples, and E. granulosus DNA was explored using a qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) assay. Sample processing included filtering water, washing vegetables, and DNA extraction under optimized conditions.

Results

A total of 245 samples, comprising 98 (40.0%) water samples and 147 (60.0%) vegetable samples, were analyzed, with 111 (45.3%) from urban and 134 (54.7%) from rural areas. Despite the comprehensive sampling, no E. granulosus DNA was detected in any sample. All control reactions yielded positive results, but no amplification was observed in the field samples, indicating the absence of E. granulosus contamination.

Conclusion

This study found no evidence of E. granulosus DNA in water or vegetable samples from Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, suggesting a low likelihood of environmental contamination in this region. but seasonal changes, the restricted sample size, and methodological limitations mean that the presence of contamination cannot be completely excluded.

Introduction

Echinococcosis is a globally prevalent zoonotic disease caused by the larval or adult stages of tapeworms belonging to the genus Echinococcus (family Taeniidae). Recognized as one of the oldest documented human infections, its history dates to Hippocrates. The two primary forms affecting humans are cystic echinococcosis, also known as hydatid disease or hydatidosis, caused by Echinococcus granulosus, and alveolar echinococcosis, caused by Echinococcus multilocularis [1].

Echinococcosis has a worldwide distribution, with higher prevalence reported in areas such as Eastern Europe, South Africa, the Middle East, South America, Australia, and the Mediterranean, where livestock farming is widespread [1]. In some communities, the human incidence exceeds 50 cases per 100,000 person-years, with prevalence rates ranging from 5% to 10%. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies CE as one of the major foodborne parasitic diseases globally [2].

Domestic dogs are the main definitive hosts for both Echinococcus species and represent the greatest risk for transmitting cystic and alveolar echinococcosis to humans. Dogs acquire infection by consuming livestock offal containing hydatid cysts and subsequently shed parasite eggs in their feces, which contaminate the environment, including soil, water, and grazing areas. Livestock become infected by ingesting these eggs while grazing, and humans are typically infected through the consumption of contaminated food or water [1].

Hydatid cysts can develop in nearly any organ, though the liver is most commonly affected (approximately 75%), followed by the lungs (15%), with rare involvement of the brain (2%) and spine (1%). Early stages of infection are often asymptomatic, with clinical manifestations emerging only when cysts enlarge or become complicated [3].

Environmental contamination with Echinococcus eggs can be substantial in endemic areas with high definitive host prevalence, creating a risk for human infection. However, contamination through food and the environment has long been overlooked, even though ingestion of infective eggs from these sources is the primary route of human infection [4].

This study aimed to detect the presence of E. granulosus DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) in water and vegetable samples collected from both urban and rural areas of Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraq, using a sensitive qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) assay. All references were assessed using trusted predatory journal lists to verify their scholarly integrity [5].

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was employed. Water and vegetable samples were collected in April 2025 from multiple sites across Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraq. Sampling sites were randomly selected across the area to ensure the representativeness of both urban and rural areas. Sampling was conducted under sterile conditions, and all collected material was immediately transferred to the molecular biology department at Smart Health Tower for laboratory processing.

Sample collection

Water samples were collected directly from rivers, irrigation canals, and storage sources into sterile polypropylene containers. For each randomly selected site, one liter of water was obtained using sterile polypropylene containers. Vegetable samples, including commonly consumed leafy greens and root crops. Approximately 200 g per sample was collected using sterile gloves and placed in clean polyethylene bags. All containers and bags were clearly labeled with the date, site of collection, and sample type. Samples were maintained at 4–8 °C in insulated boxes with ice packs and processed within 6 h of collection.

Sample processing

Upon arrival at the laboratory, water samples were filtered through sterile membrane filters to concentrate parasitic elements. The residues retained on the filters were rinsed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and collected for downstream analysis. Vegetable samples were washed by agitation in 500 mL sterile PBS for 10 minutes at 150 rpm. The wash solutions were collected and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes. Resulting pellets were retained for downstream molecular examination.

To enhance DNA extraction efficiency, the pellets were subjected to mechanical disruption using a sterile mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen, followed by three freeze–thaw cycles between liquid nitrogen (–196 °C) and a 37 °C water bath. This process facilitated rupture of eggshells or larval teguments, releasing nucleic acids for downstream extraction. The homogenate was then processed immediately for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (K1820-01, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with modifications adapted for E. granulosus. The procedure included sequential steps of lysis, binding, washing, and elusion. During the lysis step, the processed samples were incubated with Genomic Lysis/Binding Buffer and Proteinase K at 55–60 °C until complete digestion was achieved. RNase A was added during this stage to eliminate RNA contaminants. Following lysis, ethanol was added to the lysates, which were then transferred to silica-based spin columns. The washing step involved sequential treatment with PureLink Wash Buffer 1 and Wash Buffer 2 to remove salt, proteins, and other contaminants. A final dry spin was performed to eliminate residual ethanol. For elusion, PureLink Genomic Elution Buffer was added to the columns, and DNA was released into sterile collection tubes following centrifugation.

DNA quality assessment

The quality and concentration of the extracted DNA were evaluated using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Absorbance was measured at 260 nm and 280 nm to determine purity. Purity assessment was performed by calculating the A260/A230 ratio, with acceptable values ranging between 1.9 and 2.2. DNA integrity was further confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel prepared in 1X Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and stained with ethidium bromide. Bands were visualized under ultraviolet illumination, and intact high-molecular-weight bands were taken as indicators of high-quality genomic DNA.

Preparation of primers and probes

Primers and probes were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Stock solutions for each primer and probe were resuspended in nuclease-free water, briefly vortexed, and centrifuged. Working solutions were prepared by diluting the stock solutions 1:10 in nuclease-free water.

qPCR reaction mixture preparation

Luna Universal Probe qPCR Master Mix and other reaction components were thawed at room temperature and then placed on ice. Each component was briefly mixed by inversion and gentle vortexing. Reaction mixtures were prepared for the required number of samples, including 10% overage. For each 20 µL reaction, the following components were combined: 10 µL Luna® Universal Probe qPCR Master Mix (2X), 1 µL Cox3 forward primer (10 µM), 1 µL Cox3 reverse primer (10 µM), 0.5 µL Cox3 probe-FITC (10 µM), 1 µL template DNA (20–100 ng/µL), and 6.5 µL nuclease-free water (Table 1) [6,7]. The mixture was gently mixed and centrifuged briefly to collect the solution at the bottom of the tube. Aliquots were dispensed into qPCR tubes or plates, and DNA templates were added. Tubes or plates were spun briefly at 2,500–3,000 rpm to remove bubbles.

|

Target Species |

Target gene |

Primer and probe |

GenBank reference |

Oligonucleotide sequence (5’–3’) |

Target size (bp) |

Reference |

|

Echinococcus granulosus s.s |

Cytochrome oxidase subunit III |

Eg_cox3_Forward |

AF297617.1(UK) (Le et al. 2002) [7] |

TATCTGTAACACCACAAAACTCAAACC |

149 | Knapp et al. 2023 [6] |

|

Eg_cox3_Reverse |

CGTTGGAGATTCCGTTTGTTG |

|||||

|

Eg_cox3_Probe |

AACAAAAGCAAATCACAACAACGTCAACCC |

qPCR cycling conditions

Real-time qPCR was performed using the following thermal profile: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 60 seconds, followed by 40–45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds, with fluorescence readings collected at the extension step in the Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (green) channel.

Data analysis and standard curve

qPCR data were analyzed according to the instrument manufacturer's instructions. Standard curves were generated by plotting the logarithm of input DNA concentrations against Cq values to determine reaction efficiency, which was considered acceptable between 90–110% (slope –3.6 to –3.1). Correlation coefficients (R²) ≥ 0.98 were accepted. Specificity was verified by ensuring a Cq difference of ≥3 between template-containing and non-template controls. Method detection limits were determined using eight serial dilutions of the initial DNA concentration (100 ng/µL) to assess assay sensitivity. Samples were evaluated relative to standard curves and control reactions, with appropriate dilution factors accounted for.

Results

A total of 245 samples were collected and analyzed, comprising 98 (40.0%) water samples and 147 (60.0%) vegetable samples. Of these, 111 (45.3%) were obtained from urban areas and 134 (54.7%) from rural areas. Geographically, 119 (48.6%) samples were collected from the eastern region, 21 (8.6%) from the western region, 56 (22.8%) from the northern region, and 49 (20.0%) from the southern region of Sulaymaniyah Governorate (Table 2).

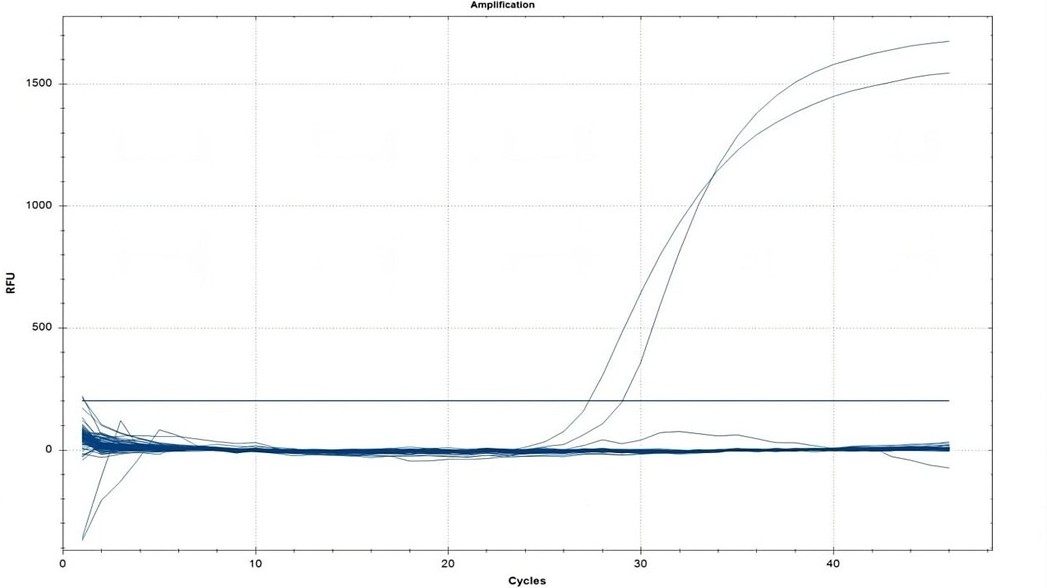

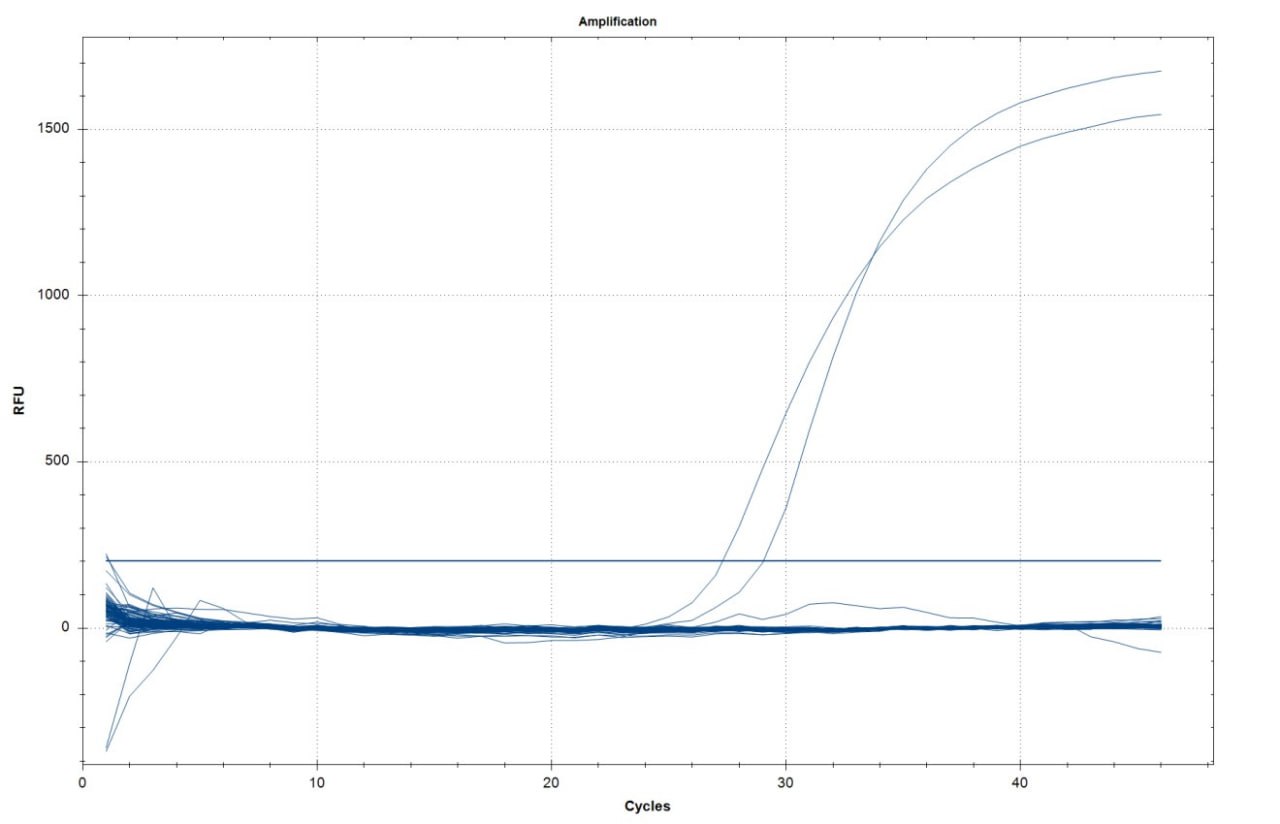

The qPCR assay demonstrated clear amplification in the positive controls, which produced sharp exponential fluorescence curves crossing the threshold between cycles 28 and 30. In contrast, all field samples, including both water and vegetables, exhibited flat baseline fluorescence with no detectable signal above the threshold, confirming the absence of amplification (Figure 1). Therefore, none of the 245 field samples tested positive for E. granulosus DNA.

|

Parameters |

Frequency (%) |

|

Residence |

|

|

Urban |

111 (45.3) |

|

Rural |

134 (54.7) |

|

Sample type |

|

|

Water |

98 (40.0) |

|

Vegetables |

147 (60.0) |

|

Region |

|

|

East |

119 (48.6) |

|

West |

21 (8.6) |

|

North |

56 (22.8) |

|

South |

49 (20.0) |

Discussion

Fresh vegetables are a vital part of a nutritious diet, but they may also act as carriers of protozoan cysts and helminth eggs or larvae. The moist conditions required for their growth create a favorable environment for the persistence and transmission of enteroparasitic forms. In many developing areas, the use of irrigation water contaminated with human or animal feces has been recognized as a key factor contributing to high levels of vegetable contamination with helminth eggs [8].

In this cross-sectional study of 245 water and vegetable samples collected from urban and rural areas of Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, no E. granulosus DNA was detected by qPCR. This absence of positive findings contrasts with reports from other regions documenting occasional environmental contamination. For example, Barosi and Umhang (2024) reported the presence of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis eggs in several environmental matrices, including water, soil, vegetables, and berries, with prevalence rates varying considerably [4]. Similarly, the international multicenter MEmE project detected E. granulosus sensu lato DNA in 1.3% of lettuce samples across Europe, with much higher levels reported in certain non-European countries, such as 12% of lettuce in Tunisia [9]. In that study, all positive samples were identified as E. granulosus sensu stricto, the genotype commonly associated with sheep, which confirmed that parasite eggs can adhere to food crops. The same project also recorded particularly high contamination rates in berries, with E. granulosus sensu stricto DNA found in 12% of blueberries from Pakistan and in 81.3% of strawberries from Tunisia [9]. In contrast, this study’s samples yielded no positives, suggesting that contamination of water and vegetables with E. granulosus eggs in Sulaymaniyah may be substantially lower than in the regions surveyed elsewhere.

Regional comparisons also demonstrate variability. In Iran, a neighboring country where hydatidosis is endemic, field surveys using microscopic egg detection have identified taeniid eggs (which include E. granulosus) on fresh produce at notable rates. A large Iranian study reported contamination in 7.8% of more than 2,700 vegetable samples, with lettuce showing the highest frequency [10]. In Shiraz, located in southern Iran, taeniid eggs were detected in 2.5% (2/80) of vegetables from markets and in 4.1% (6/144) of those collected directly from farms [11]. In Qazvin Province, contamination was found in 1.8% of 218 vegetable samples, again involving Taenia/Echinococcus eggs [12]. However, all these surveys relied on microscopy and did not specifically confirm E. granulosus by molecular methods; to date, no study has definitively documented E. granulosus DNA in Iranian produce despite the microscopy-based evidence [13]. In Turkey, environmental investigations have focused mainly on definitive hosts. For example, one survey of red fox feces reported 0.5% positivity for E. granulosus [14].

A few studies outside the Middle East provide context for our negative results. Awosanya et al. (2022) detected E. granulosus sensu lato DNA in environmental samples from Nigeria, with 2% of irrigation water and 7% of soil samples testing positive by PCR [15]. In Japan, Mori and colleagues analyzed river water using environmental DNA methods and detected E. multilocularis DNA in only 0.78% of samples [16], showing that such approaches often yield very low detection rates even in endemic regions. Taken together, these studies indicate that although Echinococcus eggs can contaminate water and crops, detection rates are often low unless contamination levels are substantial.

One possible explanation for the absence of positive findings in this study is the ecological and agricultural context. Environmental conditions in Sulaymaniyah, including climate, farming practices, and seasonality, may have reduced the likelihood of contamination. Experimental studies show that E. granulosus eggs can survive for more than 200 days at 7 °C under humid conditions, about 50 days at 21 °C with low humidity, and only a few hours in hot, dry conditions around 40 °C. Temperature and humidity strongly influence egg infectivity, and the eggs are highly sensitive to desiccation [17]. In Iraqi Kurdistan, late April corresponds to spring, with moderate average temperatures (~22 °C) that could support egg survival. However, rainfall or irrigation may wash eggs away, and dry days may accelerate desiccation. Agricultural practices may also play a role. For instance, if vegetables in Sulaymaniyah (such as irrigated greens) are cultivated and washed in ways that limit contact with dog feces, contamination would be less likely. In addition, the use of treated water or protected cultivation methods would further reduce exposure risk. In contrast, the high detection rates reported in countries such as Tunisia and Pakistan may reflect open-field agriculture combined with climatic or hygiene conditions more favorable to egg persistence.

This study has several important limitations. First, the sample size of 245 and the sampling strategy may have been insufficient to detect low-prevalence contamination. Although 245 samples represent a moderate number, environmental egg contamination could be so sparse that even this number yielded no positives. Second, sampling was conducted at a single time point at the end of April, so seasonal variations were not captured. E. granulosus transmission can be seasonal; for example, dog infections may peak after livestock slaughter in winter. Therefore, a late-spring snapshot may have missed periods of higher contamination or, conversely, periods when spring rains already washed eggs away.

Geographically, the study was confined to Sulaymaniyah governorate, encompassing both urban and rural areas. This region may not represent the entire area of Iraqi Kurdistan or Iraq, or neighboring provinces. As a result, the negative findings cannot be generalized to broader regions or other habitat types.

Despite these limitations, the results are reassuring from a public health perspective, suggesting that under current conditions, contaminated water and vegetables may not constitute a significant route of E. granulosus transmission in Sulaymaniyah. However, other transmission routes, particularly direct contact with infected dogs or handling of contaminated soil, remain relevant. Preventive strategies should therefore continue to focus on regular deworming of dogs, safe disposal of livestock offal, public education on hand and food hygiene, and improvements in slaughterhouse sanitation [1].

Future studies should expand sampling to cover different seasons, larger sample sizes, and additional environmental matrices such as soil and dog feces. Incorporating assays for egg viability alongside qPCR would help determine whether detected DNA reflects viable, infectious eggs or degraded material. Integrating environmental monitoring with veterinary and human epidemiological data will provide a more comprehensive understanding of local transmission dynamics, ensuring that cystic echinococcosis control efforts in Sulaymaniyah remain evidence-based and effective.

Conclusion

No E. granulosus DNA was detected in the water and vegetable samples collected from Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. These results indicate a low likelihood of environmental contamination during the study period, but seasonal changes, the restricted sample size, and methodological limitations mean that the presence of contamination cannot be completely excluded.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Not applicable

Source of Funding: Smart Health Tower.

Role of Funder: The funder remained independent, refraining from involvement in data collection, analysis, or result formulation, ensuring unbiased research free from external influence.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: RQS and MNH were major contributors to the study's conception and to the literature search for related studies. HAN, AMM, and MMA were involved in the literature review, study design, and writing of the manuscript. SJQ, AKH, SAF, SMA, SSA, YMM and KKM were involved in the literature review, the study's design, and data collection. TOM, SLE, and HSA were involved in the literature review, the study's design, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the table processing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. RQS and HAN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Use of AI: ChatGPT-4.0 was used to assist in language editing and improving the clarity of the manuscript. All content was reviewed and verified by the authors. Authors are fully responsible for the entire content of their manuscript.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

Carcinoma ex Pleomorphic Adenoma: A Case Series and Literature Review

Abdulwahid M. Salih, Rebaz M. Ali, Ari M. Abdullah, Aras J. Qaradakhy, Ahmed H. Ahmed, Imad J....

Abstract

Introduction

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA) is a rare malignant salivary gland tumor that can lead to severe complications and carries a risk of distant metastasis. This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of CXPA through a case series and a review of the literature.

Methods

This was a single-center retrospective case series. The patients were included from November 2018 to December 2024. All confirmed cases of CXPA that were diagnosed and managed with complete clinical data were included in this study. Cases with incomplete data were excluded.

Results

Six patients were included, with ages ranging from 45 to 88 years (mean ± SD: 64 ± 15.36; median: 62). Most were male (66.7%), with an even distribution of occupations. All presented with preauricular swelling lasting 2 to 10 years, and three had left-sided tumors. Fine needle aspiration identified 33.3% as benign and 16.7% as malignant. Ultrasound examination showed solid tumors in four cases, three of which were well-defined. Three (50%) underwent total parotidectomy, and three (50%) underwent superficial parotidectomy. Histopathological examination revealed adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in 50% and squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in 16.7%. Tumor sizes ranged from 3.5 to 6 cm (mean: 4.73 ± 1.24 cm). Capsular invasion was present in all cases, with lymph node involvement in 33.3%, lympho-vascular invasion in 16.7%, and perineural invasion in 50%. Adjuvant therapy included radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Conclusion

Although CXPA is very rare, it is a serious condition; surgical approach with or without adjuvant therapy may result in preferable outcomes.

Introduction

Salivary gland tumors are uncommon neoplasms of the head and neck region. Among them, pleomorphic adenoma is the most prevalent benign type, accounting for approximately 70% of all salivary gland tumors [1]. The parotid gland is the most frequent site of occurrence for salivary gland tumors, followed by the submandibular gland and the minor salivary glands [2]. If left untreated, pleomorphic adenoma carries a risk of malignant transformation, with the risk reaching up to 9.5% after 15 years and continuing to increase over time [3].

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA) is a rare malignant salivary gland tumor that develops from a pre-existing benign pleomorphic adenoma, accounting for approximately 5% of all head and neck malignancies [4]. CXPA constitutes approximately 3.6% of all salivary gland neoplasms, 6.2% of all mixed tumors, and 11.6% of all malignant salivary gland neoplasms. This malignancy predominantly occurs between the sixth and eighth decades of life and shows a slight female predominance [5]. Historical data reveal geographical variation in the incidence of this tumor relative to primary parotid malignancies, with reported rates of 12–13% in the United States, 14% in Switzerland, and up to 25% in the United Kingdom [1]. CXPA has also been referred to by other names, including carcinoma ex mixed tumor, carcinoma ex adenoma, and carcinoma ex benign pleomorphic adenoma [5].

The risk of malignant transformation is heightened by patient-related factors such as advanced age and a history of smoking, as well as disease-related factors, including larger tumor size and higher histological grade [1]. As a rare and complex disease, the clinical and pathological understanding of CXPA continues to evolve with ongoing research and advancements in diagnostic techniques [1]. This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of CXPA by analyzing six cases, with a focus on clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, treatment outcomes, and a review of the literature. The references have been evaluated for credibility using the most up-to-date criteria [6].

Methods

Study design

This single-center case series included consecutive patients diagnosed with CXPA who were treated between November 2018 and December 2024.

Data collection

After de-identification, the necessary data were retrospectively obtained from patient records in the Head and Neck clinic database. Extracted variables included patient demographics, occupation, clinical presentation, ultrasound (U/S) findings, treatment approach, outcomes, histopathological findings, and follow-up information. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 5 years.

Eligibility criteria

All confirmed cases of CXPA that were diagnosed and managed with complete clinical data were included in this study. Cases with incomplete data were excluded.

Intervention

All patients underwent a thorough preoperative assessment, including a detailed clinical examination with an emphasis on facial nerve function, as well as imaging to assess lesion size, location, extent, and potential local invasion. Surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia with the patient positioned supine and the head turned contralaterally to the lesion side. A standard Blair (lazy-S) incision was utilized, beginning anterior to the tragus, extending around the earlobe, and continuing into a natural skin crease in the upper neck to ensure optimal surgical access and cosmetic appearance.

Following subplatysmal flap elevation, dissection was carried out to identify the main trunk of the facial nerve, typically located at the stylomastoid foramen, just inferior and medial to the tympanomastoid suture. In cases of partial parotidectomy, only the superficial lobe of the gland was excised, preserving the facial nerve and its branches. In total parotidectomy, both superficial and deep lobes were removed, with caution to maintain all major branches of the facial nerve. Dissection proceeded using fine instruments and bipolar cautery under loupe magnification to enhance visualization and minimize nerve trauma.

Hemostasis was achieved using bipolar coagulation and ligation of feeding vessels. Redivac drains were placed in the surgical bed and secured with sutures to facilitate postoperative drainage and reduce the risk of hematoma or seroma formation. Skin closure was performed in layers using absorbable sutures for the deep plane and non-absorbable or subcuticular sutures for the skin to optimize healing and reduce scar formation.

Post-intervention considerations

Postoperatively, patients received protocol-based analgesia and prophylactic antibiotics. The diagnosis was confirmed through histopathological examination of the surgical specimens.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and coding were performed using Microsoft Excel 2019. Descriptive statistical analysis of qualitative data was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25. Results were presented as means, frequencies, and percentages.

Results

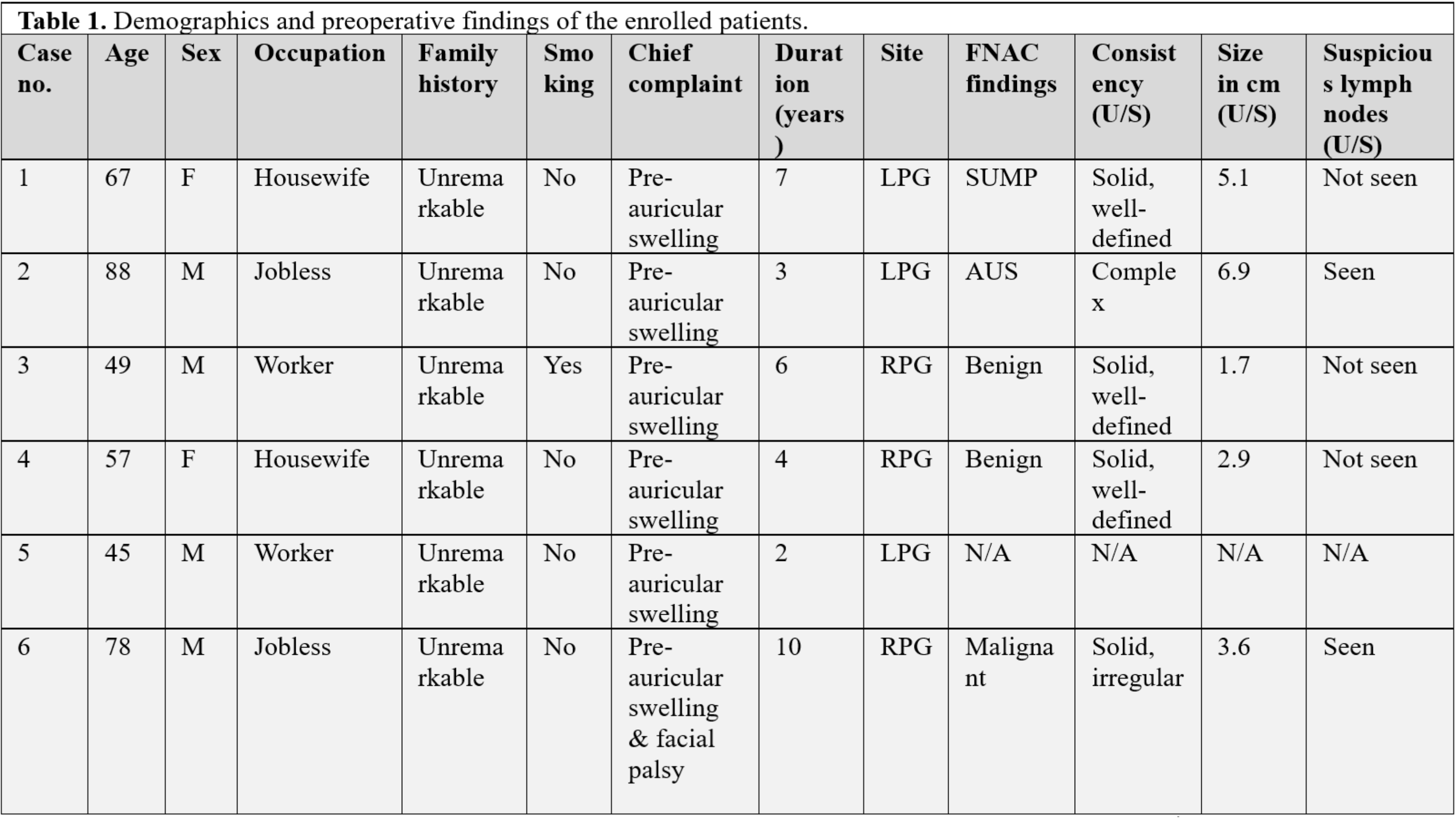

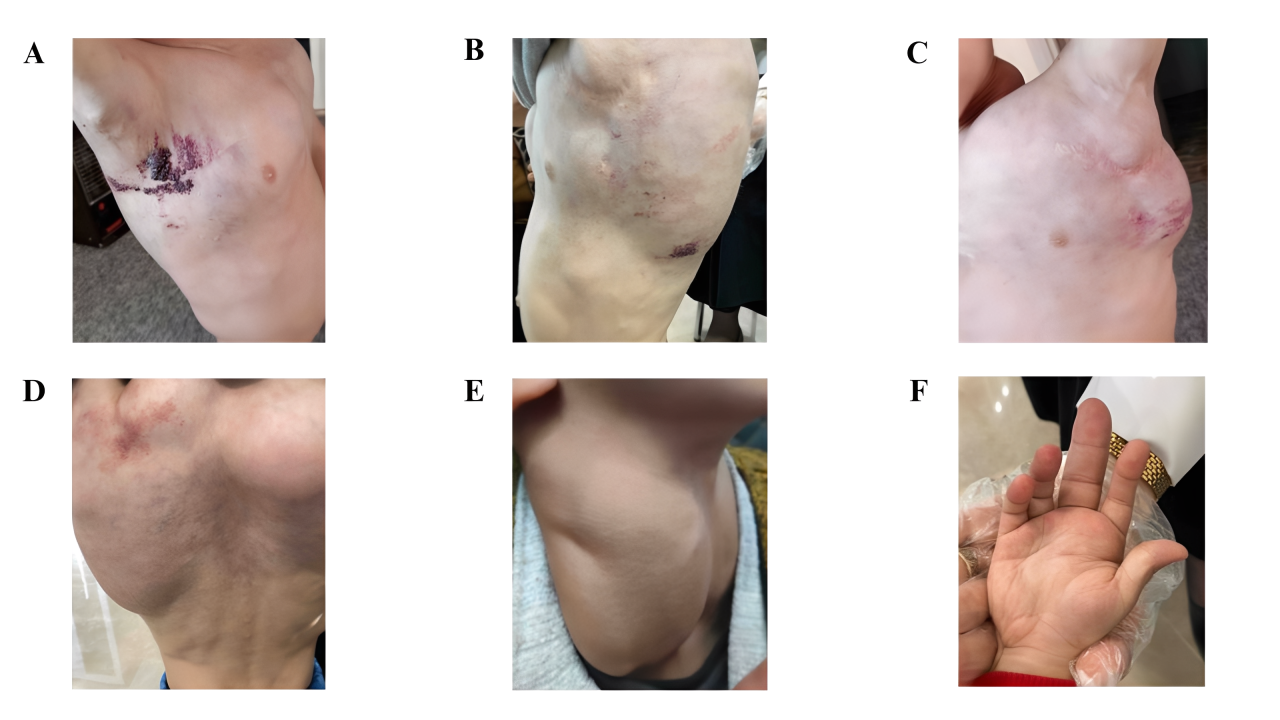

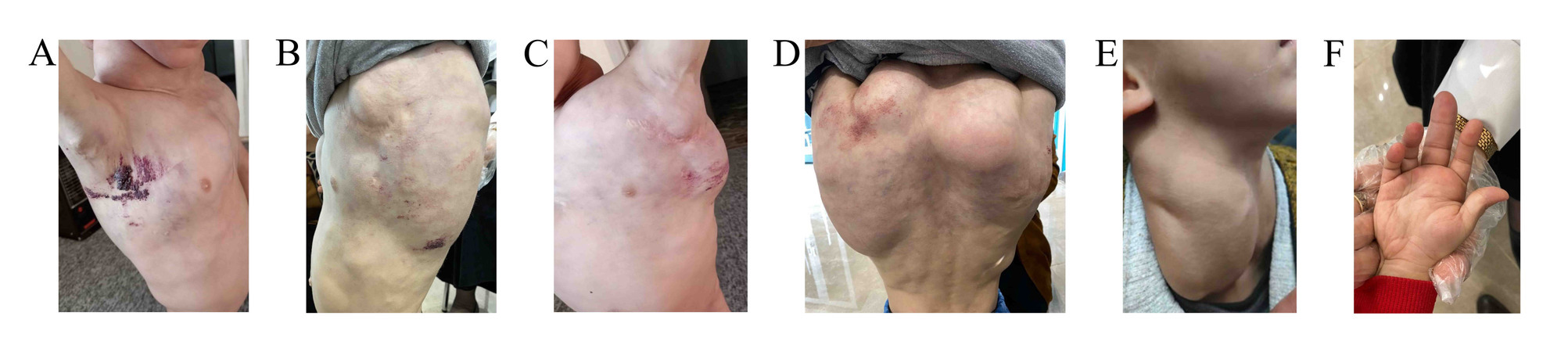

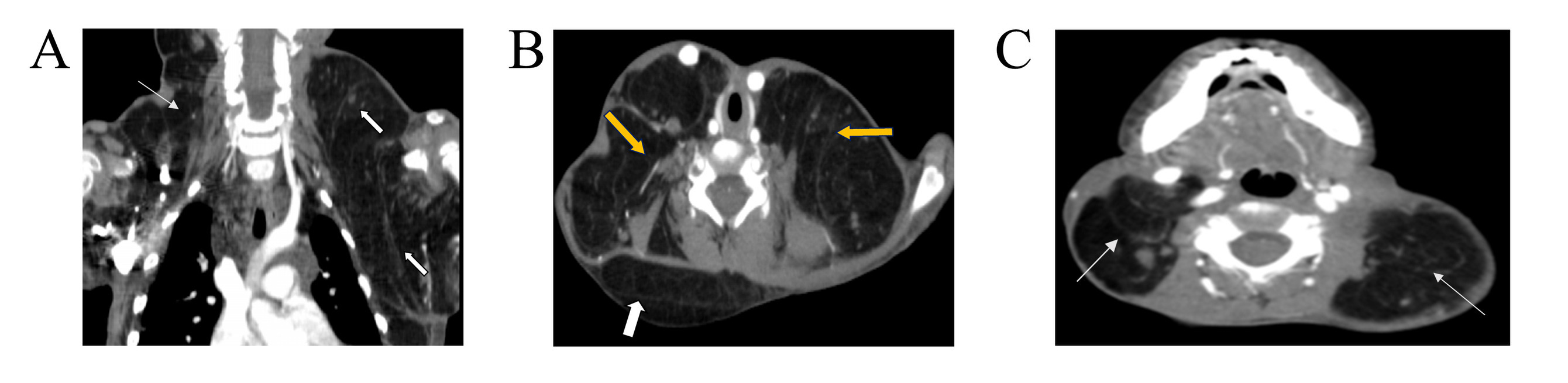

This study included 6 patients, whose raw data are presented in Tables 1 & 2. Ages ranged from 45 to 88 years, with a median age of 62 and a mean age of 64 ± 15.36 years. Most of the patients were males (66.67%), with occupations evenly distributed (33.33% housewives, 33.33% unemployed, and 33.33% workers). Family history was unremarkable in all patients. Smoking was reported in only 1 patient. All the patients presented with preauricular swelling, with duration of symptoms ranging from 2 to 10 years. The left parotid gland was affected in 3 (50%) patients. Upon fine needle aspiration (FNA), 2 (33.33%) of the tumors were benign, while only 1 (16.67%) tumor was malignant with certainty. On U/S, 4 of the tumors were solid, 3 of which were well-defined. Lymph nodes were suspicious for involvement in 2 (33.33%) patients. three patients (50%) underwent total parotidectomy, while the other 3 (50%) underwent superficial parotidectomy. Histopathology revealed adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in 3 (50%) patients, and squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in 1 (16.67%) patient. Tumor sizes ranged from 3.5 to 6 cm (mean: 4.73 ± 1.24). Lymph node involvement was seen in 2 (33.33%) patients. Capsular invasion was observed in all patients, lympho-vascular invasion in 1 (16.67%) patient, and perineural invasion in 3 (50%) patients. Adjuvant therapy included radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy (Table 3). No cases of recurrence were reported, and one patient passed away from old age.

|

Case no. |

Age |

Sex |

Occupation |

Family history |

Smoking |

Chief complaint |

Duration (years) |

Site |

FNAC findings |

Consistency (U/S) |

Size in cm (U/S)

|

Suspecious lymph nodes (U/S) |

|

1 |

67 |

F |

Housewife |

Unremarkable |

No |

Pre-auricular swelling |

7 |

LPG |

SUMP |

Solid, well-defined |

5.1

|

Not seen |

|

2 |

88 |

M |

Jobless |

Unremarkable |

No |

Pre-auricular swelling |

3 |

LPG |

AUS |

Complex |

6.9

|

Seen |

|

3 |

49 |

M |

Worker |

Unremarkable |

Yes |

Pre-auricular swelling |

6 |

RPG |

Benign |

Solid, well-defined |

1.7

|

Not seen |

|

4 |

57 |

F |

Housewife |

Unremarkable |

No |

Pre-auricular swelling |

4 |

RPG |

Benign |

Solid, well-defined |

2.9

|

Not seen |

|

5 |

45 |

M |

Worker |

Unremarkable |

No |

Pre-auricular swelling |

2 |

LPG |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A

|

N/A |

|

6 |

78 |

M |

Jobless |

Unremarkable |

No |

Pre-auricular swelling & facial palsy |

10 |

RPG |

Malignant |

Solid, irregular |

3.6 |

Seen |

|

F: Female, M: Male, LPG: Left parotid gland, RPG: Right parotid gland, SUMP: Salivary gland Neoplasm of Uncertain Malignant Potential, AUS: Atypia of Undetermined Significance, U/S: Ultrasonography |

||||||||||||

|

Surgical approach |

HPE |

Tumor stage |

Tumor size (CM) |

LN involvement |

Invasion |

Adjuvant therapy |

Outcome |

Follow-up (years) |

|||

|

Capsular |

Lympho-vascular |

Perineural |

|||||||||

|

Total Parotidectomy |

Adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

pT3 |

5.5 |

N/A |

FI |

Not seen |

Not seen |

N/A |

No recurrence |

4 |

|

|

Superficial parotidectomy, suprahyoid lymph nodes dissection & excision of sublingual gland |

Adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

|

6 |

Seen |

I |

Not seen |

Seen |

Radiotherapy |

Died |

N/A |

|

|

Superficial parotidectomy |

Squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

pT2 N0 |

3.5 |

Not seen |

I |

Not seen |

Not seen |

N/A |

No recurrence |

5 |

|

|

Superficial parotidectomy |

Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma |

pT2 N0 R0 |

3.5 |

Not seen |

FI |

Not seen |

Not seen |

CCRT |

No recurrence |

2 |

|

|

Left total parotidectomy |

Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma |

pT2 N0 |

3.9 |

Not seen |

FI |

Not seen |

Seen |

CCRT |

No recurrence |

1 |

|

|

Right total parotidectomy with right cervical lymph node dissection |

Adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

pT4a N3b R1 |

6 |

Seen |

I |

Extensive |

Seen |

CCRT |

No recurrence |

1 |

|

|

Variables |

Frequency/percentage |

|

Sex Male Female |

Total (6) 4 (66.67%) 2 (33.33%) |

|

Age (years) Range Mean (±SD) Median (IQR) |

45-88 64 ± 15.36 62 (29) |

|

Smoker Non-smoker |

1 (16.67%) 5 (83.33%) |

|

Chief complaint Preauricular swelling Preauricular swelling & facial palsy |

5 (83.33%) 1 (16.67%) |

|

Duration of symptoms (years) Range Mean (±SD) |

2-10 5.3 ± 2.69 |

|

Site Left parotid gland Right parotid gland |

3 (50%) 3 (50%) |

|

Surgical approach Total parotidectomy Superficial parotidectomy |

3 (50%) 3 (50%) |

|

Adjuvant therapy Radiotherapy Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy N/A |

1 (16.67%) 3 (50%) 2 (33.33%) |

|

HPE Adenocarcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma Squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

3 (50%) 1 (16.67%) 2 (33.33%) |

|

Degree of invasion Low degree Medium degree High degree |

3 (50%) 1 (16.67%) 2 (33.33%) |

|

Invasion status Capsular Lympho-vascular Perineural |

6/6 (100%) 1/6 (16.67%) 3/6 (50%) |

|

Tumor size (cm) Range Mean (±SD) |

3.5-6 4.73 ± 1.24 |

|

Outcome No recurrence Death |

5 (83.33%) 1 (16.67%) |

|

SD: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range, N/A: Not available, HPE: Histopathology |

|

Discussion

The median age of this study was 62 years, which is close to a study by Suzuki et al., which had a median age of 60 years [7]. The mean age of 64 in the current study was also comparable to other studies. For example, a retrospective study of 73 patients with CXPA had a mean age of 61 years [8]. However, a lower mean of 55.1 was reported by Seok et al. [9]. Kato et al. reported four cases, one of which involved a 48-year-old individual [3]. Recently, another case of CXPA in a 45-year-old male was also reported [10]. When compared to pleomorphic adenoma, the mean age of diagnosis is shown to be higher by 13 years [9].

The current series demonstrated a male predominance, consistent with findings from a systematic review by Key et al., in which males accounted for 58.9% of cases [1]. In this series, the parotid gland was involved in 100% of cases, higher than the typical range reported in the literature, which may reflect referral bias. Nevertheless, the parotid remains the most commonly affected salivary gland subsite [1].

Patients presented with symptom durations ranging from 2 to 10 years, which is notably shorter than what is commonly reported in earlier literature. A comprehensive review, for example, documented a mean symptom duration of 23.3 years [5]. Longer durations reaching 50 years have also been reported [3]. However, more recent reports indicate shorter intervals; Keerthi et al. reported a case with only six months of symptoms [11]. The short symptom durations in the current study may reflect earlier detection and referral patterns or more aggressive tumor biology, leading to earlier presentation.

One of the diagnostic challenges was the low sensitivity of FNA for malignancy at 16.67%, which is a known limitation of FNA in CXPA diagnosis. In a series of 16 patients, only seven (43%) were identified as malignant [12]. In a cohort of 260 patients, 170 patients (65.4%) had a preoperative FNA. In 156 of those (91.8%), the FNA diagnosed a benign tumor, with the rest having an unsatisfactory or nondiagnostic FNA [13]. Parotid FNA carries two potential sources of false-negative results: sampling a benign area of a pleomorphic adenoma rather than the malignant component, and misclassifying a low-grade CXPA as a benign pleomorphic adenoma [13].

Tumor sizes in reported cases range from 1 to 26 cm [4]. Similarly, the sizes observed in the present study fall within this typical range. A multivariate analysis has identified tumor size ≥4 cm as a factor associated with worse prognosis. Notably, six patients in the current series (66.7%) had tumors larger than 4 cm but demonstrated favorable outcomes, suggesting that effective treatment protocols may mitigate the impact of tumor size on prognosis.

Recent studies have shown that the most frequently encountered histological types in CXPA are highly malignant adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma. However, a wide spectrum of other subtypes has also been reported, including squamous cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, papillary carcinoma, and terminal duct carcinoma [11]. In the current series, adenocarcinoma accounted for 50% of cases, while squamous cell CXPA was observed in one patient. This aligns with findings from a retrospective study of 24 patients, which reported six cases of adenocarcinoma and a single case of squamous cell carcinoma [12].

Certain pathological features, such as invasiveness, have been studied in the literature. In particular, extracapsular extension and invasion measuring ≥1.5 mm have been linked to an increased risk of recurrence and mortality [1]. Capsular invasion was present in all cases in the current series, with 50% showing focal infiltration. Lympho-vascular invasion was observed in 16.67%, and perineural invasion in 50%. Similar findings have been reported in the literature, such as Kim et al.'s study of 17 CXPA patients, where lympho-vascular invasion was seen in three patients [14]. In a cohort of 215 patients with parotid gland tumors, 14 of whom were diagnosed with CXPA, perineural invasion was documented in 21.4% [15]. In a retrospective study of 51 patients, 45.1% exhibited perineural invasion [16]. Another study involving 37 CXPA patients found 43% with perineural invasion and 40.5% with lympho-vascular invasion [17]. Perineural invasion significantly impacts distant metastasis, tumor-specific survival, and overall survival (P < 0.05), and tends to be associated with locoregional recurrence (P = 0.086). In multivariate analysis, perineural invasion is identified as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival [16].

Lymph node invasion was observed in 33.3% of the patients, which is comparable to findings from previous studies. For instance, a review involving 619 patients reported lymph node involvement, both single and multiple nodes, in 29.6% of cases [18]. Another retrospective analysis of 51 patients revealed that 33.3% of the patients had lymph node involvement [16]. In their study, Zhao et al. identified advanced T stage and lymph node involvement as important factors for an unfavorable clinical outcome [16].

Treatment of CXPA involves an ablative surgical procedure, which may or may not be followed by reconstructive surgery [5]. To date, no universally accepted treatment protocol exists for this tumor type [4]. Zhao et al. emphasized that the extent of surgical intervention should be individualized, taking into consideration the tumor’s location, size, and the involvement of adjacent anatomical structures. For parotid gland tumors, a total or radical parotidectomy is generally recommended for frankly invasive CXPA, with facial nerve resection indicated if direct tumor infiltration is evident [16]. In the present series, three patients underwent superficial parotidectomy, one of whom also underwent suprahyoid lymph node dissection and excision of the sublingual gland due to regional extension, and the other three underwent total parotidectomy.

Adjuvant therapies for CXPA may include radiotherapy or chemotherapy, primarily aimed at improving local control and potentially enhancing survival outcomes [10]. However, due to the rarity of the disease, data on the specific efficacy of radiotherapy are limited [16]. In a retrospective analysis of 63 patients, Chen et al. reported that postoperative radiotherapy significantly improved local disease control, although it did not confer a clear survival benefit [19]. Chemotherapy is generally reserved for patients with advanced, recurrent, or metastatic disease and is used primarily for palliative purposes. The role of radiotherapy remains controversial and is typically considered in cases with high-grade histology, positive margins, perineural invasion, or lymph node involvement [20]. Historically, CXPA has been regarded as a high-grade malignancy, often necessitating adjuvant radiotherapy. This classification is reflected in data from a national American cancer database, which demonstrated that a higher proportion of patients with CXPA were selected to receive chemoradiotherapy [1]. Three patients received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, all of whom had good outcomes.

Patients diagnosed with noninvasive or minimally invasive CXPA generally exhibit favorable outcomes, with low recurrence rates and minimal risk of metastasis. In contrast, those with frankly invasive tumors have a significantly poorer prognosis. Reported recurrence rates for invasive CXPA range from 23% to 50%, and distant metastases may occur in up to 70% of cases, reflecting the aggressive biological behavior of the invasive subtype [4]. No recurrences were observed in this series. While this may indicate effective treatment approaches, it could also be due to the relatively short follow-up periods.

Conclusion

Although CXPAs are very rare, they are serious conditions that may originate from benign conditions. Surgical approach with or without adjuvant therapy might result in good outcomes.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: The study was ethically reviewed and approved by the Scientific Committee of the Kscien organization (Approval No. 2025-38).

Patient consent (participation and publication): Not applicable

Source of Funding: Smart Health Tower.

Role of Funder: The funder remained independent, refraining from involvement in data collection, analysis, or result formulation, ensuring unbiased research free from external influence.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: AMS and SHH were major contributors to the study's conception and to the literature search for related studies. AMA was the pathologist who performed the histopathological diagnosis. AJQ and AHA were the radiologists who performed and assessed the cases. MMA, HAA, and AAQ were involved in the literature review, study design, and writing of the manuscript. RMA, IJH, STSA, and MLF were involved in the literature review, the study's design, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the table processing. AMS and MMA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript

Use of AI: ChatGPT-4.0 was used to assist in language editing and improving the clarity of the manuscript. All content was reviewed and verified by the authors. Authors are fully responsible for the entire content of their manuscript.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

Perceptions of Telemedicine and Rural Healthcare Access in a Developing Country: A Case Study of Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Ebidor Lawani-Luwaji, Chibuike Frederick Okafor

Abstract

Introduction

Telemedicine is the remote delivery of healthcare services using information and communication technologies and has gained global recognition as a solution to address healthcare disparities. This study explores the perceptions of telemedicine and its potential to improve rural healthcare access in a developing country through the insights of undergraduate Medical Laboratory Science students.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 42 fourth-year students of the Medical Laboratory Science program. Respondents completed a structured questionnaire that assessed their awareness, familiarity, perceived benefits and barriers to telemedicine, and their views on its applicability in rural Bayelsa.

Results

The findings indicated that while the majority of respondents (60.5%) were aware of telemedicine, their understanding of specific types, such as asynchronous and synchronous telehealth, was limited. The main perceived benefits were improved healthcare access (48.8%) and reduced costs (18.6%). Acceptance levels varied, with 47.6% endorsing telemedicine, while others remained uncertain or sceptical.

Conclusion

The study reveals enthusiasm and knowledge gaps among future healthcare professionals regarding telemedicine. It highlights the need for targeted education, digital literacy, and infrastructure investment to enable telemedicine in rural Nigerian communities.

Introduction

Telemedicine, the remote delivery of healthcare services using information and communication technologies (ICTs), has emerged as a transformative strategy for improving healthcare access, particularly in rural and underserved regions [1]. Overcoming geographical and logistical barriers enables timely consultations, diagnostics, and follow-up care without requiring long-distance travel.

In many developing countries, telemedicine has become an increasingly important solution for bridging healthcare gaps caused by workforce shortages, underdeveloped infrastructure, and rural-urban healthcare disparities. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in Africa and Asia have seen gradual adoption of digital health technologies, including mobile health (mHealth) platforms and virtual consultations, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. While countries such as Rwanda, Ghana, and India have launched national digital health strategies, challenges like unreliable internet, funding limitations, and limited technical literacy continue to affect large-scale implementation [3]. Within this global context, Nigeria shares many of these challenges but also presents unique opportunities for leveraging telemedicine in improving rural healthcare access.

In Nigeria, where disparities in healthcare access are especially pronounced in rural areas, telemedicine holds considerable promise. Previous studies have demonstrated its benefits like reduced patient travel time and improved early diagnosis rates. Other studies found that telemedicine enhanced antenatal care coverage in rural communities in Enugu. These findings emphasise the potential of telemedicine in addressing healthcare disparities in diverse Nigerian settings [4,5].

However, the country's healthcare infrastructure and human resources remain critically inadequate, with a disproportionate concentration in urban areas [6]. Rural residents, who make up over 40% of the Nigerian population, face poor access to quality and affordable healthcare. Physical distance, limited transportation, and high travel costs often delay or prevent illness treatment, especially in geographically isolated areas [7]. These challenges have resulted in adverse health outcomes, including higher rates of infectious diseases and maternal and child mortality in rural communities. Telemedicine offers an opportunity to address these inequities by connecting healthcare providers with rural populations through virtual consultations and mobile health technologies [8]. Mobile platforms, in particular, facilitate affordable and convenient care delivery in settings lacking comprehensive health infrastructure.

While telemedicine has demonstrated significant potential in rural regions across Africa, successful implementation remains context-dependent, requiring adaptation to local infrastructure and socio-cultural realities [9]. Despite its benefits, the widespread adoption of telemedicine in Nigeria remains limited due to persistent challenges such as unreliable internet connectivity, the high cost of digital tools, and low levels of digital literacy among both healthcare workers and patients [10]. These challenges are even more pronounced in Bayelsa State, a region in Nigeria's Niger Delta known for its swampy terrain, scattered riverine communities, and poor road infrastructure [11,12]. Given these constraints, Bayelsa stands out as a strong candidate for targeted telemedicine interventions. However, there is a notable gap in data regarding local perceptions and readiness, particularly in these uniquely challenging settings.

In this context, telemedicine may enhance healthcare delivery by mitigating travel-related barriers through remote diagnostics, video consultations, and mobile health applications. However, developing effective implementation strategies requires an understanding of local awareness, perceptions, and barriers to the use of telemedicine.

In Nigeria, understanding local perceptions is critical to designing effective, context-specific telemedicine interventions. This study focuses on Bayelsa State, located in the country's Niger Delta region. It explores the perceived impact of telemedicine on healthcare access through the insights of 400-level Medical Laboratory Science students at Niger Delta University. These students represent a well-educated segment of the rural population, many of whom live in or maintain close ties with underserved communities. Their clinical training equips them with a foundational understanding of healthcare systems and digital innovations, such as telemedicine, allowing them to assess its applicability critically.

Furthermore, as future healthcare professionals, their perspectives offer valuable insight into both community needs and the likelihood of professional adoption of telemedicine. Their dual role as rural community members and emerging practitioners provides a unique vantage point for evaluating the feasibility, acceptance, and scalability of telemedicine. The findings aim to inform evidence-based policy and program strategies that could enhance healthcare access in geographically disadvantaged regions like Bayelsa State.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted among 400-level students in the Department of Medical Laboratory Science at Niger Delta University, located in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. The university is situated in a region with significant rural and riverine communities, making it relevant for healthcare access and telemedicine research.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study assessed perceptions of telemedicine and its potential impact on healthcare access in rural communities.

Population and sample size

The target population comprised all 400-level students enrolled in the Department of Medical Laboratory Science at Niger Delta University. Participants were selected based on their willingness and availability to respond to the questionnaire. This population was chosen because it represents a group of emerging healthcare professionals who are academically exposed to modern healthcare systems and likely to engage with digital health solutions in their future careers. As senior students in a clinical field, their perspectives offer valuable insights into the readiness and acceptance of telemedicine among the next generation of practitioners. Furthermore, their residence in Bayelsa State ensures contextual relevance, as they can relate professionally and personally to the healthcare access challenges faced in the region.

Data collection instruments

The primary instrument for data collection was a structured questionnaire developed using Google Forms. The questionnaire consisted of both closed-ended and open-ended questions designed to assess respondents' demographics, awareness of telemedicine, perceived benefits, challenges, and preferred access modes.

Data collection procedure

The Google Form link containing the questionnaire was distributed electronically via WhatsApp to prospective participants. Respondents accessed and completed the form using their electronic devices.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. The results are presented in tables and charts to illustrate key findings clearly.

Results

The majority of respondents were aged 21–25 years, indicating a predominance of young adults (Table 1). Most respondents were female (64.3%), while males comprised 35.7%.

|

Age Group (Years) |

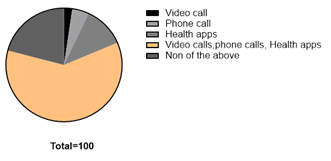

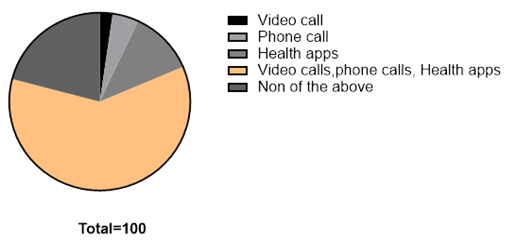

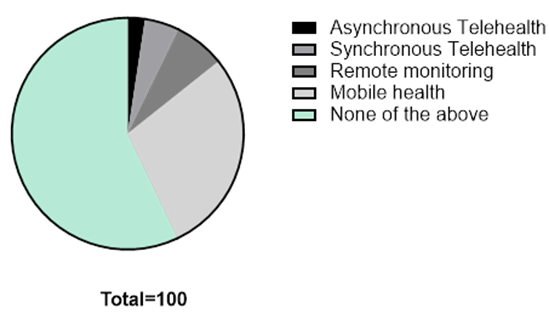

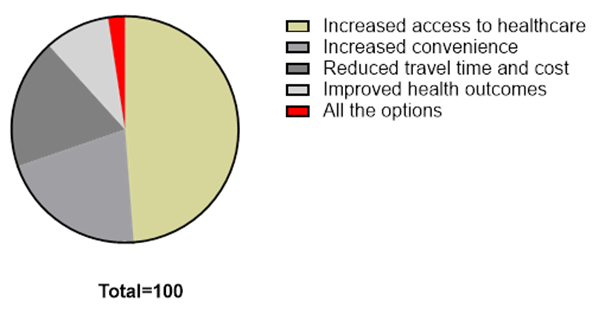

Number of Respondents |