Vol 4, No 1 (2026): Current Issue (Volume 4, Issue 1), 2026

Editorial

Evolving Challenges in Modern Qualitative Research

Snur Othman

Qualitative research works at revealing the depth of human experiences, cultural nuances, and complex social dynamics, yet it confronts formidable challenges including pervasive researcher subjectivity, methodological inconsistencies, ethical intricacies, resource burdens, data management overload, and struggles with establishing rigor and transferability that often invite skepticism from quantitative paradigms. These obstacles not only complicate the research process but also threaten the perceived validity and broader applicability of findings in fields like health, education, and social sciences. Addressing them requires deliberate strategies to fortify qualitative inquiry's contributions to knowledge [1].

Subjectivity and Researcher Bias

The interpretive essence of qualitative research inherently invites researcher bias, as personal worldviews, cultural backgrounds, and preconceptions influence every stage from question formulation to data interpretation. For example, during thematic analysis of interviews, a researcher's emphasis on certain participant quotes might overlook contradictory evidence, leading to unbalanced narratives. Mitigation strategies like reflexivity where researchers explicitly document their influences and triangulation, cross-verifying data from multiple sources, prove essential, though full elimination of subjectivity remains impractical in this paradigm [2].

Methodological Design and Rigor Hurdles

Crafting a robust qualitative design demands precise alignment between philosophical underpinnings, research questions, and methods such as phenomenology, grounded theory, or discourse analysis, yet mismatches frequently occur due to insufficient expertise. Determining data saturation when new data yields no fresh insights relies on subjective judgment, complicating claims of completeness, while ensuring transferability to other contexts necessitates detailed "thick descriptions" of participants and settings. In health research, these issues amplify without clear audit trails, prompting calls for standardized rigor criteria akin to quantitative benchmarks [3].

Data Collection and Management Complexities

Gathering qualitative data through prolonged interviews, focus groups, or ethnographies generates vast, unstructured volumes of transcripts, field notes, and multimedia that overwhelm storage, organization, and preliminary sorting. Logistical barriers, like recruiting hard-to-reach participants or adapting to virtual formats, further delay progress, while ensuring consistency across sessions proves elusive without rigid protocols. Digital tools offer relief for transcription and initial coding, but they demand technical proficiency and risk diluting contextual richness if misapplied [1-4].

Analysis and Interpretation Demands

Transforming raw qualitative data into coherent themes involves iterative coding, pattern identification, and narrative synthesis, a labor-intensive process prone to interpretive drift among team members. Balancing depth with transparency challenges researchers, especially when handling ambiguous or contradictory data, and emerging AI aids accelerate this but introduce concerns over algorithmic bias eroding human insight. Peer debriefing, inter-coder reliability checks, and software like NVivo enhance trustworthiness, yet the time investment often months strains projects and underscores the need for advanced training [4].

Ethical, Practical, and Interdisciplinary Tensions

Ethical navigation intensifies in qualitative work due to intimate participant interactions, raising issues like securing ongoing consent, safeguarding anonymity in sensitive topics, and managing power imbalances with vulnerable groups. Practical constraints, including high costs for fieldwork and participant fatigue, compound these, while interdisciplinary skepticism particularly from STEM fields questions replicability and generalizability. Mixed-methods integration and decolonial approaches that center marginalized voices offer bridges, but they require institutional support and evolved review board processes [5].

Emerging Trends and Solutions

Technological innovations like AI-driven analysis and big data integration promise efficiency, yet they challenge traditional methodological purity and amplify ethical risks around data privacy. Postqualitative and indigenous methodologies push boundaries by rejecting linear processes, fostering inclusivity amid globalization. Researchers advance by prioritizing comprehensive training, open-access protocols for auditability, and collaborative networks to elevate qualitative work's stature and impact.

Conflicts of interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Original Articles

Could first-trimester bleeding affect a newborn's Apgar score?

Leila Sekhavat, Atiyeh Javaheri

Abstract

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding is a common complication during pregnancy and may contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of first trimester bleeding on newborns Apgar scores.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on pregnant women who delivered at Shahid Sadoughi hospital in Yazd, Iran, between 2022 and 2023. Only singleton, nulliparous, non-diabetic women were included. Participants were divided into two groups: the exposure group (Bleeding Group) and control Group (Non-Bleeding Group), based on archived records. Apgar scores recorded at the first and fifth minutes after birth in newborns file were compared between groups.

Results

A total of 992 women were included, with 218 in the exposure and 774 in the control groups. The incidence of a first-minute Apgar score <7 was significantly higher in the bleeding group compared to controls (22.5% vs. 6.2%, p = 0.02). However, there was no significant difference in five-minute Apgar scores between groups.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a positive association between first-trimester vaginal bleeding and a low first-minute Apgar score in newborns.

Introduction

The first trimester of pregnancy is a crucial period of fetal development, during which the body undergoes significant physiological changes to support the growing baby [1]. Maternal and fetal well-being are closely interconnected, and multiple factors influence fetal growth and metabolic programming.

First trimester bleeding defined as vaginal bleeding occurring between conception and 12 weeks of gestation. It is common and affecting between 16 - 25% of all pregnancies and often causes anxiety for both patients and clinicians [2-4]. Although many pregnancies with first-trimester bleeding progress without complication, emerging evidence suggests an increased risk of neonatal complications later in pregnancy [5,6]. The Apgar score, developed by Dr. Virginia Apgar in 1952, is a rapid and reliable method of assessing newborn condition and clinical status immediately after delivery [7-9]. The score is reported at one and five minutes after birth and, if below 7, at five-minute intervals up to 20 minutes [10]. Approximately 1% of low-risk live births have a five-minute Apgar score below 7, which is associated with a significantly higher risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality [11]. Low Apgar scores have also been linked to long-term adverse outcomes such as epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and developmental delays [12-14].

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between first-trimester bleeding and neonatal health. Some of these studies indicate a correlation between first-trimester bleeding and low Apgar scores at the first and fifth minutes after birth [5,15-17]. Conversely, other studies have reported that first-trimester bleeding has no effect on newborn Apgar scores [18-21].

Several studies have explored the association between first-trimester bleeding and neonatal outcomes, with mixed results. Some found a correlation between early bleeding and low Apgar scores [5,15–17]. The others reported no significant relationship [18–21]. Some evidence suggests that only when bleeding results in complications such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm birth, or low birth weight does it significantly affect neonatal Apgar scores [5,22,23].

This study aims to further investigate the relationship between first-trimester bleeding and neonatal Apgar scores.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was designed as a retrospective study. Data were collected from archived files at the hospital and medical records of pregnant individuals who delivered at Shahid Sadoughi hospital in Yazd, Iran, during one year.

Inclusion criteria

This study included singleton pregnancies that resulted in the delivery of live newborns at or beyond 37 weeks of gestation, with a birth weight greater than 2500 grams.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnancies were excluded if there were fetal anomalies, chronic maternal diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, renal, cardiac, or endocrine disorders, or any history of smoking or drug abuse. Additional exclusions included surgical conditions during pregnancy, multiple gestations, placental abruption or placenta previa in the later trimesters, and cases with incomplete medical records.

Grouping and data collection

Participants were categorized into two groups: an exposure group, consisting of pregnancies complicated by first-trimester vaginal bleeding, and a control group, comprising pregnancies without first-trimester bleeding. All included women were under 40 years of age. Demographic characteristics such as occupation, economic status, educational level, and maternal body mass index (BMI) were obtained. Clinical data were extracted from archived hospital records and patients' files, including obstetric history and detailed documentation of any first-trimester bleeding episodes. First-trimester vaginal bleeding was defined as bleeding occurring before 12 weeks of gestation in the presence of a closed cervix and a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Newborn outcomes, including Apgar scores at one and five minutes, were also retrieved from medical records. An Apgar score <7 at either time point was considered low, with scores classified as normal (>7), low (5–7), or very low (<5).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test, while categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 992 term singleton pregnancies were included in the analysis, comprising 218 women in the exposure (bleeding) group and 774 in the control group. Maternal and neonatal characteristics of both groups are presented in (Table 1).

|

Maternal characteristics |

Exposure group (first trimester bleeding) N = 218 |

Control group (without bleeding) N= 774 |

P-value |

|

Age in years N (%) <20 20 – 30 31 – 40 |

45 (20.6) 146 (67) 27 (12.4) |

155 (20) 513 (66.3) 106 (13.7) |

0.2 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) N (%) <18 18– 25 >25 |

38 (17.4) 145 (66.5) 35 (16.1) |

148 (19.1) 490 (63.3) 136 (17.6) |

0.1 |

|

Employment N (%) Yes No |

98 (44.9) 120 (55.1) |

379 (49) 395 (51) |

0.7 |

|

Educational level < 12 >12 |

66 (30.3) 152 (69.7) |

241 (31.1) 533 (68.9) |

0.4 |

|

Prenatal care Adequate Inadequate |

99 (45.4) 119 (54.6) |

363 (46.9) 411 (53.1) |

0.3 |

Newborns in the bleeding group had a significantly higher proportion of first-minute Apgar scores <7 compared with the control group (22.5% vs. 6.2%, p = 0.02). Although five-minute Apgar scores <7 were also more common among the bleeding group (8.7% vs. 6.7%), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.6) (Table 2).

| Neonatal Apgar score |

Exposure group (first trimester bleeding) N = 218 |

Control group (without bleeding) N= 774 |

P-value |

|

First min APGAR scores N (%) <7 >7 |

49 (22.5) 169 (77.5) |

48 (6.2) 726 (93.8) |

0.02 |

|

5 min after birth APGAR scores N (%) <7 >7 |

19 (8.7) 199 (91.3) |

52 (6.7) 722 (93.3) |

0.6 |

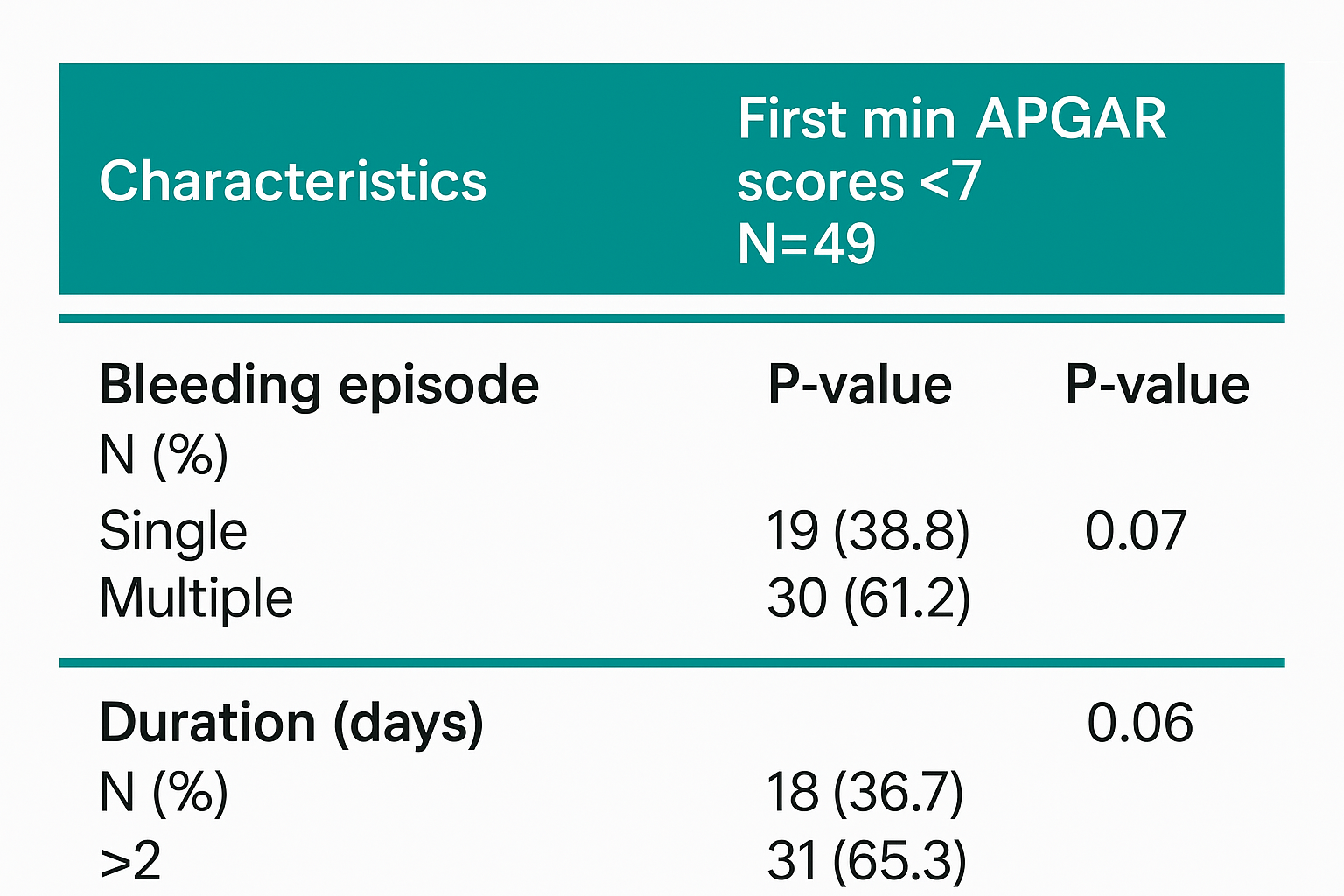

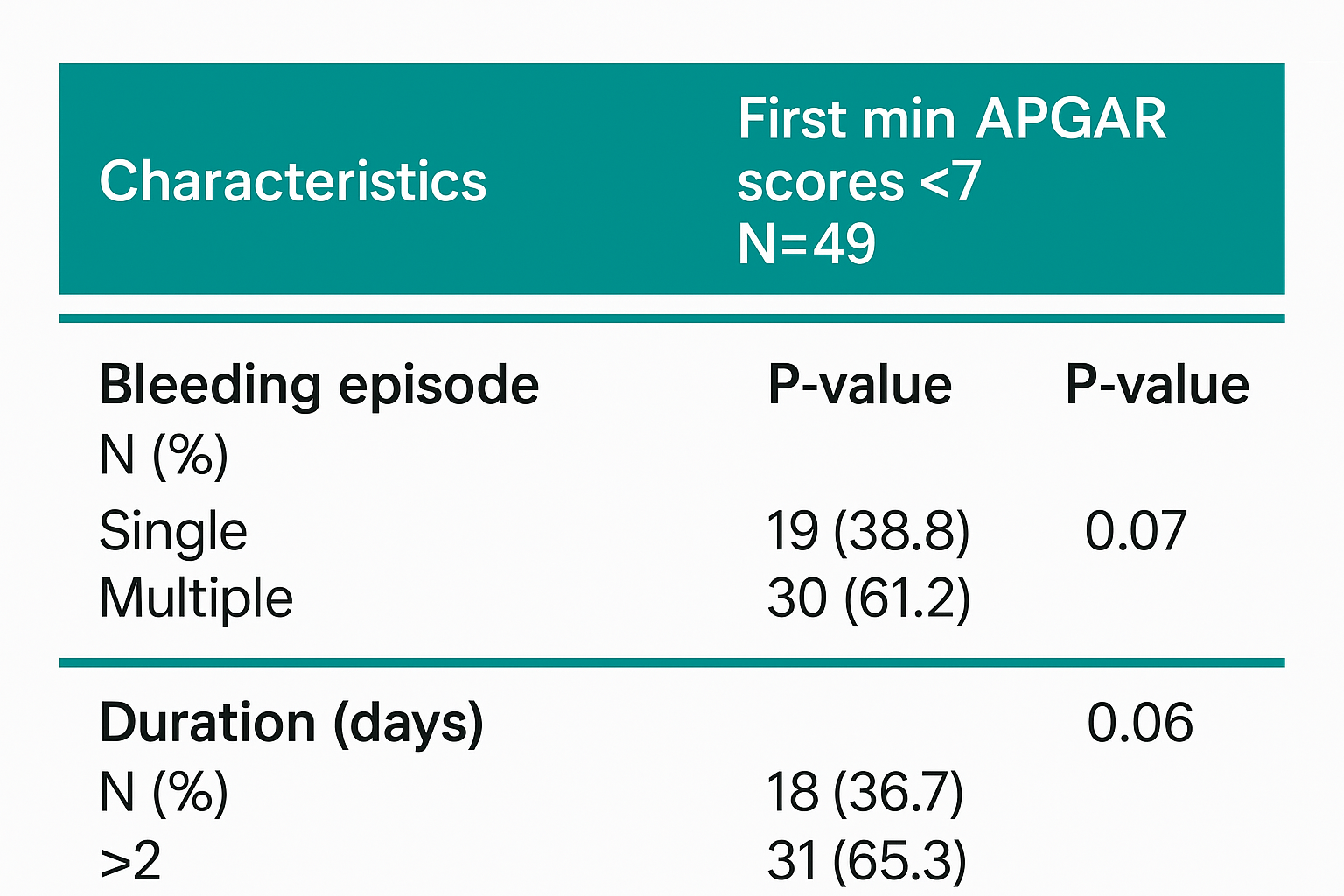

Women who experienced bleeding lasting more than two days had a greater frequency of low first-minute Apgar scores (65.3%) than those with shorter-duration bleeding (36.7%); however, this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Similarly, multiple bleeding episodes were associated with a higher proportion of low Apgar scores compared with single episodes, but without statistical significance (p = 0.07) (Table 3).

|

Characteristics |

First min APGAR scores <7 N=49 |

P-value |

|

Bleeding episode N (%) Single Multiple |

19 (38.8) 30 (61.2) |

0.07 |

|

Duration (days) N (%) 1– 2 > 2 |

18 (36.7) 31 (65.3) |

0.06 |

The mean birth weight of newborns was 2891 ± 539 g. While low birth weight was more common in the bleeding group, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4). Overall, these findings suggest that first-trimester vaginal bleeding is associated with an increased risk of a low first-minute Apgar score at birth.

|

Neonatal birth weight (gm) |

Exposure group (first trimester bleeding) N = 218 |

Control group (without bleeding) N= 774 |

P-value |

|

LBW (<2500) N (%) |

48 (22) |

147 (19) |

0.07 |

|

Normal weight (2500-4000) N (%) |

159 (72.9) |

563 (72.7) |

0.4 |

|

Macrosomia (> 4000) N (%) |

11 (5.1) |

64 (8.3) | 0.2 |

Discussion

This study found a significant association between first-trimester vaginal bleeding and low one-minute Apgar scores. The Apgar score is a key indicator of neonatal health, and lower values often reflect perinatal distress and risk of complications such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and NICU admission [10,12].

One of the most significant findings in this study was Neonates born to mothers with first-trimester bleeding were more likely to have a one-minute Apgar <7 (22.5% vs. 6.2%, p = 0.02). This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that early pregnancy bleeding may compromise fetal growth and lead to neonatal distress [5,6,15-17,24].

Karimi et al. reported in their meta-analysis that vaginal bleeding during pregnancy is a risk factor for adverse outcomes, including low Apgar scores and preterm birth [5]. Bever et al. found that first-trimester bleeding was linked to altered fetal growth patterns, which can contribute to neonatal distress and first minute low Apgar [6]. Some of these studies indicate a correlation between first-trimester bleeding and low Apgar scores at one and five minutes of birth [15-17, 24].

The underlying mechanism may involve placental dysfunction. Early bleeding may indicate subchorionic hematoma or implantation abnormalities, which can reduce placental efficiency and lead to fetal hypoxia. Gaillard et al. [1] reported that placental dysfunction adversely affects fetal growth and development, potentially manifesting as low Apgar scores. Maternal inflammation during early bleeding episodes may also negatively influence fetal development [15].

Although, some studies conversely have reported that first-trimester bleeding has no effect on newborn Apgar scores [18- 21], therefore, it seems that more studies are needed in this objective.

The absence of a significant difference in five-minute Apgar scores in our study the groups (bleeding: 8.7% vs. control: 6.7%, p = 0.6) suggests that prompt neonatal care and resuscitation may mitigate initial distress. This finding is consistent with Chen et al, who suggested that while low five-minute Apgar scores are predictive of long-term adverse outcomes, short-term resuscitation efforts often improve neonatal condition [11]. Current guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that neonates with low Apgar scores receive immediate and thorough evaluation to mitigate the risks associated with potential perinatal asphyxia [7].

Longer or recurrent bleeding episodes appeared to increase the risk of low Apgar scores, though not significantly. Chandrakala and Reshmi similarly noted that recurrent bleeding episodes often indicate placental dysfunction and can contribute to perinatal morbidity [24].

Although low birth weight was more common in the bleeding group, the difference was not statistically significant, differing from studies by Karimi et al, and Velez et al, possibly due to differences in population size and inclusion criteria [5,22]. The discrepancy may be attributed to variations in study populations, sample sizes, and differing criteria for defining low birth weight.

Conclusion

This study underscores the importance of vigilant prenatal monitoring in pregnancies affected by early first-trimester bleeding. Further investigations are required to identify predictors of adverse neonatal outcomes and to develop preventive measures that may enhance newborn health.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and utilized data obtained from hospital archives.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Was obtained from all participants prior to completing the questionnaire, and participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Funding: The present study received no financial support.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the residents of the Obstetrics and Pediatrics Departments at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran, for their assistance in data collection, and the Department of Statistics for support with data analysis.

Authors' contributions: LS Contributed to drafting the manuscript and critically revising its content, and approved the final version prior to submission. AJ Responsible for data acquisition, study conception and design, as well as data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Use of AI: AI was not used in the drafting of the manuscript, the production of graphical elements, or the collection and analysis of data.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

Impact of Common Anticoagulants on Complete Blood Count Parameters Among Humans

Rawezh Q. Salih, Dahat A. Hussein, Sharaza Q. Omer, Shvan L. Ezzat, Ayman M. Mustafa, Hawnaz S....

Abstract

Introduction

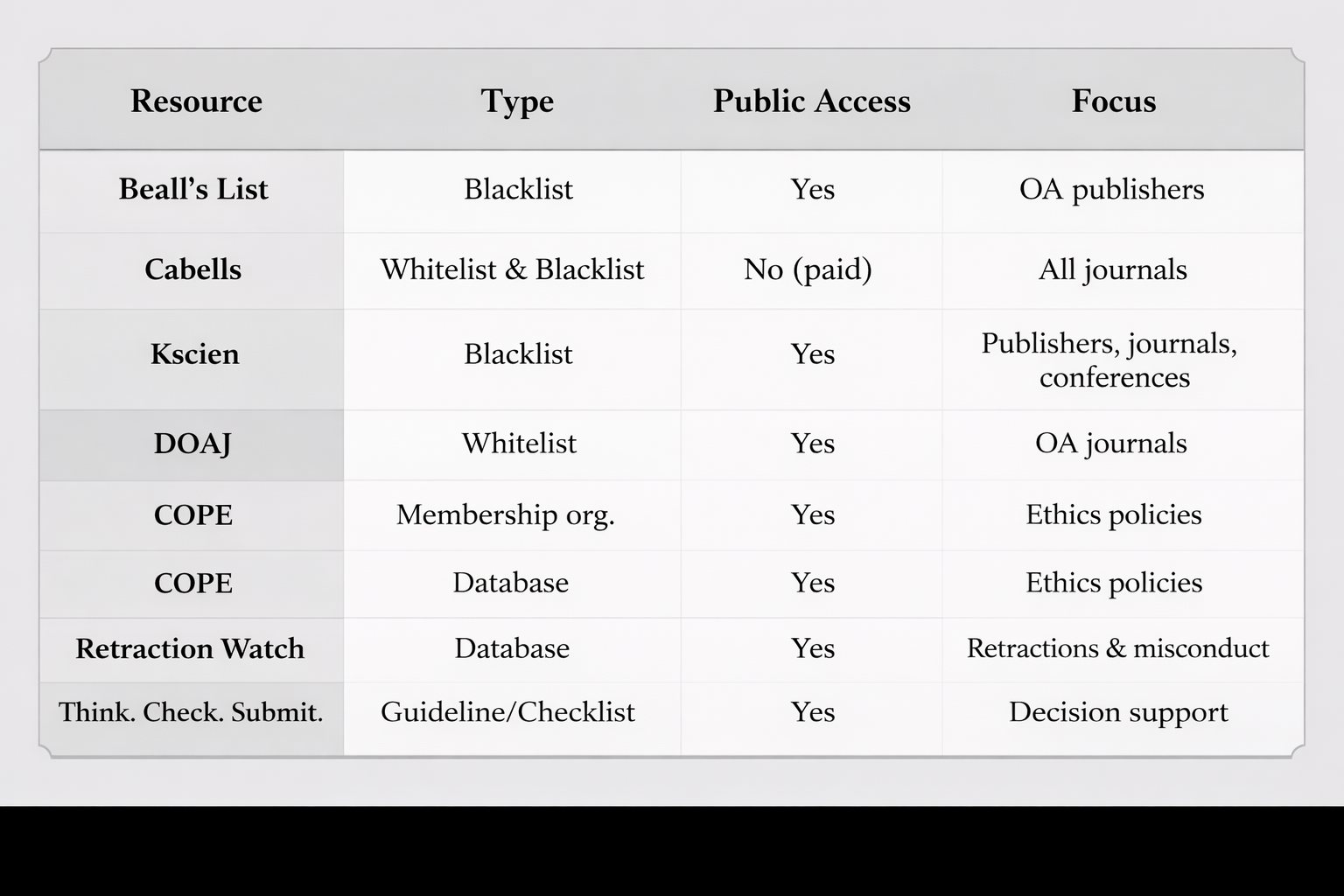

Among the most frequently used anticoagulants in hematological testing are tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), sodium citrate, and sodium heparin. However, there is a noticeable gap in literature concerning the effects of these anticoagulants on hematological parameters specifically in humans. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin for conducting complete blood count (CBC).

Methods

This cross-sectional study conducted at Smart Health Tower from January to April 2024 involved 250 participants who underwent CBC using K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin. The acquired data were analyzed using SPSS, with a significance level of p < 0.05, employing Intra-class correlation coefficient and one-way ANOVA to assess consistency and agreement among anticoagulants.

Results

A total of 250 participants, with 138(55.2%) males and 112(44.8%) females, underwent CBC testing with di potassium EDTA(K2EDTA), sodium citrate, and sodium heparin. Comparing K2EDTA with sodium heparin showed comparable values in 14 out of 23(60.87%) CBC parameters. Using K2EDTA as the standard, citrate showed perfect or substantial agreement in assessing 8 out of 23 CBC parameters (34.78%). Regarding the comparison of anticoagulants to K2EDTA to determine their agreement levels while sodium heparin was accurate and precise in 13(56.52%) parameters.

Conclusion

Citrate was found to be a less reliable anticoagulant for CBC estimation compared to K2EDTA, potentially leading to inaccurate readings. On the other hand, sodium heparin showed comparable performance to K2EDTA, making it a suitable alternative under specific conditions.

Introduction

The Complete Blood Count (CBC) is a widely requested blood test by clinicians, assessing the total quantities and characteristics of cellular constituents within the bloodstream. The CBC parameters include red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets (PLTs). This comprehensive assessment includes determining the total and differential count of WBCs, also measuring RBC count, hemoglobin (HGB) levels, and hematocrit (HCT), as well as their indices such as mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and red cell distribution width (RDW). Additionally, CBC evaluates platelet (PLT) count indices [1,2]. A CBC serves as an important diagnostic tool for assessing human health, detecting congenital abnormalities, and identifying functional changes due to various pathological factors [3]. Its findings can reveal various conditions such as infections with elevated WBC counts, leukemia with abnormal WBC counts, anemia with low HGB levels, and liver cirrhosis with reduced PLT counts. Recent studies suggest that specific combinations of CBC components, along with derived secondary results, can predict risks of different diseases like cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [1,2].

It's widely recognized that collection and sampling of blood, laboratory techniques and storage conditions, and the choice of anticoagulant can substantially impact the outcomes derived from hematological analysis, especially CBC results [4]. Among the various anticoagulants used for both sample collection and routine laboratory analysis, the most commonly utilized ones in hematology are ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), citric acid salts, sodium and lithium oxalates, and heparin [5,6].

The National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards has suggested using EDTA for CBC due to its ability to preserve cell structure [7]. However, limited evidence exists on the effects of other anticoagulants on CBC parameters among animal species. Among humans, heparin is typically avoided for blood smears and WBC counts due to staining and clotting issues, respectively. Conversely, EDTA is considered unsuitable for erythrocyte osmotic fragility assessment and may cause cell damage if overused [8].

The majority of studies documented in existing literature have focused on evaluating the impacts of different anticoagulants on CBC results or its specific components across diverse animal species. The current study aims to estimate variations in CBC parameters using different anticoagulants, employing dipotassium EDTA(K2EDTA), sodium citrate, and sodium heparin, among humans to evaluate their effectiveness.

Methods

Study Design, population, and criteria

This cross-sectional laboratory-based study was conducted at Smart Health Tower from January to April 2024. Prior to participation, all individuals were thoroughly briefed about the study and required to provide informed written consent. The study included a total of 250 participants, all of whom underwent complete blood count tests utilizing K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin as anticoagulants. The study population consisted of patients attending Smart Health Tower, representing both genders without any gender bias. Inclusion was restricted to those who had visited the facility, while individuals or their guardians ( in case of minors) who declined to provide consent were excluded from the study.

Determination of the sample size

The effective sample size was determined using G*Power statistic 3.1.9.7, employing linear multiple regression as the statistical test with a two-tailed approach. With an effective sample size of 0.35, an α error probability of 0.01, and a statistical power of 0.99, along with a predictor value of 1, the minimum required sample size was 158. Therefore, a sample size of 250 was utilized for the comparison in CBC parameters between these three different anticoagulants.

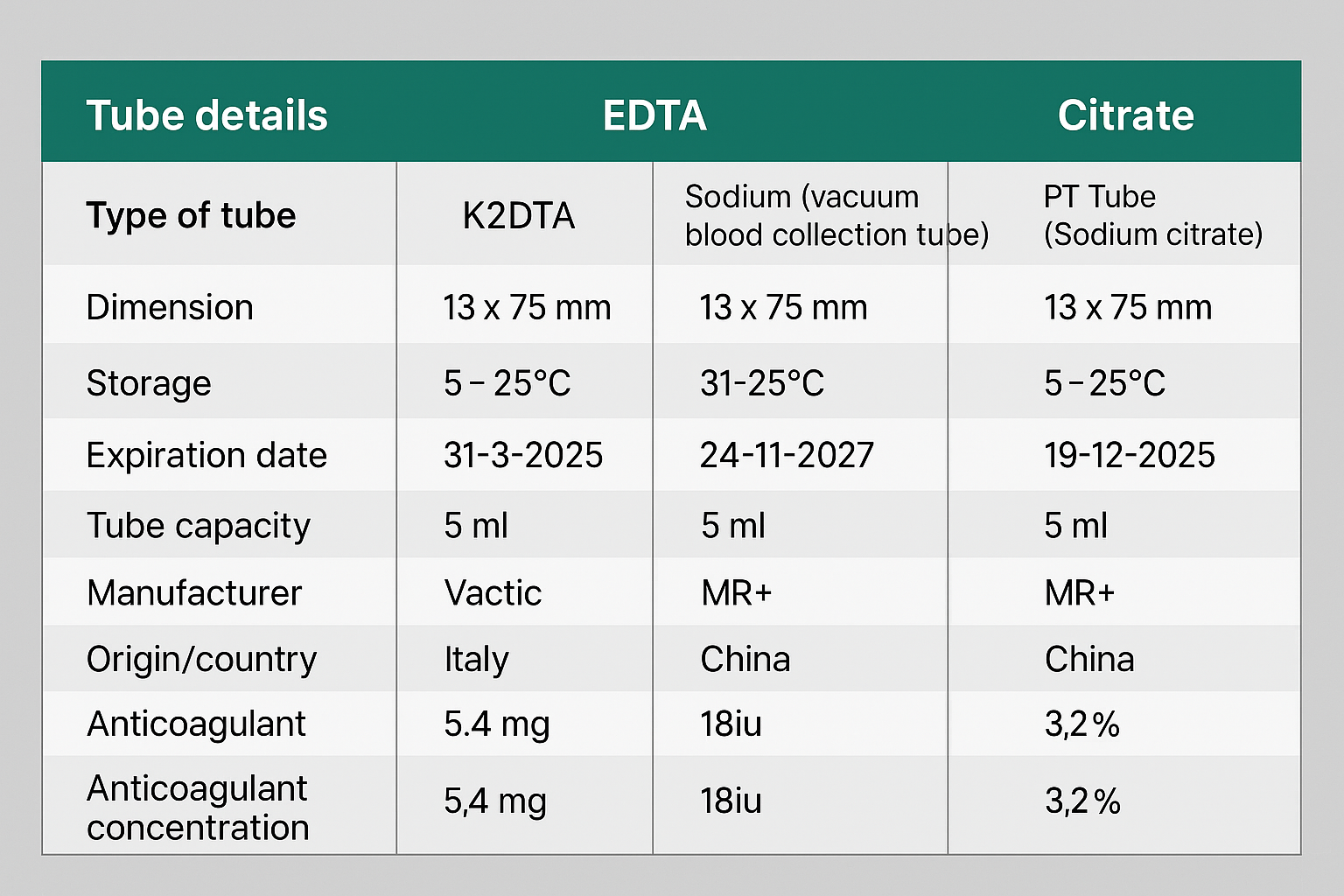

Sample collection and statistical analysis

Trained health workers collected blood samples from participants using sterile syringes and needles, drawing 5 mL from either the median cubital or prominent forearm vein. The samples were distributed as follows: 1.8 mL into sodium citrate tubes and 1.6 mL into K2EDTA and sodium heparin tubes. After gentle mixing, complete blood counts (CBC) were analyzed with the Medonic M51 automated hematology analyzer within 3 to 6 hours post-collection. Tube characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Various hematological parameters were assessed, including WBC, percentages of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, as well as RBC, HCT, HGB, MCV, MCHC, RDW-SD, PLT, MPV, PDW, PCT, and PLCR. Participant demographics, such as age and gender, were also recorded. Data were initially processed in Microsoft Excel 2019 for accuracy and completeness before being transferred to SPSS version 25.0 and MedCalc version 20 for statistical analysis. Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis was conducted to evaluate consistency among the three anticoagulants, with interpretations as follows: <0.50 for poor consistency, 0.50-0.75 for moderate, 0.75-0.90 for good, and >0.90 for excellent consistency. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. One-way ANOVA assessed variations in CBC parameters among samples collected in K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin tubes. Additionally, the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) was used to evaluate agreement, with K2EDTA as the standard, and interpreted as follows: ≥0.99 for almost perfect agreement, 0.95-0.99 for significant agreement, 0.90-0.95 for moderate agreement, and <0.90 for poor agreement [9].

|

Tube details |

EDTA |

Heparin |

Citrate |

|

Type of tube |

K2EDTA |

Sodium (vacuum blood collection tube) |

PT Tube (Sodium citrate) |

|

Dimension |

13 x 75 mm |

13 x 75 mm |

13 x 75 mm |

|

Storage |

5- 25°C |

5-25°C |

5-25°C |

|

Expiration date |

31-3-2025 |

24-11-2027 |

19-12-2025 |

|

Tube capacity (volume) |

5 ml |

5 ml |

5ml |

|

Required volume |

1.5-2 ml |

1.5-2ml |

1.8ml |

|

Tube material |

Plastic |

glass |

glass |

|

Manufacturer |

Vacutest kima sri |

MR+ |

MR+ |

|

Origin/country |

Italy |

China |

China |

|

Anticoagulant concentration |

5.4 mg |

18iu |

3.2% |

Results

Among the 250 participants involved, 138 (55.2%) were male, and 112 (44.8%) were female. The participants had an average age of 41.20 ± 16.51 years (5-91). Consistency in CBC results using sodium heparin, K2EDTA, and sodium citrate indicated excellent consistency in the determination of WBC, %Neu, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, RBC, HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW-SD, MPV, PDW, and PLCR among these anticoagulants with ICC >0.90 (Table 2).

|

CBC parameters |

Intra-class correlation coefficient |

Confidence interval 95% |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

||

|

WBC |

0.991 |

0.972 |

0.996 |

|

%Neu |

0.961 |

0.880 |

0.981 |

|

%Lymph |

0.987 |

0.984 |

0.990 |

|

%Mon |

0.494 |

0.038 |

0.717 |

|

%Eos |

0.869 |

0.838 |

0.895 |

|

%Bas |

0.733 |

0.636 |

0.801 |

|

Neu |

0.988 |

0.961 |

0.994 |

|

Lymph |

0.987 |

0.973 |

0.993 |

|

Mon |

0.612 |

0.120 |

0.802 |

|

Eos |

0.182 |

0.038 |

0.367 |

|

Bas |

0.803 |

0.719 |

0.858 |

|

RBC |

0.922 |

0.328 |

0.976 |

|

HGB |

0.923 |

0.321 |

0.976 |

|

HCT |

0.902 |

0.449 |

0.964 |

|

MCV |

0.998 |

0.994 |

0.999 |

|

MCH |

0.996 |

0.992 |

0.998 |

|

MCHC |

0.963 |

0.921 |

0.979 |

|

RDW-SD |

0.924 |

0.901 |

0.941 |

|

PLT |

0.536 |

0.276 |

0.689 |

|

MPV |

0.915 |

0.843 |

0.948 |

|

PDW |

0.921 |

0.880 |

0.945 |

|

PCT |

0.563 |

0.104 |

0.763 |

|

PLCR |

0.930 |

0.856 |

0.960 |

Regarding variation in CBC parameters using K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin, no statistically significant variation was found in the median %Lymph, Eos, MCV, and MCH among these three different anticoagulants (Table 3).

|

CBC parameters |

Sodium Heparin Median (Min-Max) |

Citrate |

K2EDTA |

P-value |

|

WBC |

7.54(2.52-26.26) |

7.21(2.26-23.85) |

7.51(2.54-26.10) |

0.046 |

|

%Neu |

61.15(37.2-92.6) |

56.70(37.60-90.90) |

56.30(30.70-91.80) |

<0.001 |

|

%Lymph |

33.2(3.8-50.30) |

33.55(4-50.50) |

33.45(3.90-52.60) |

0.718 |

|

%Mon |

1.9(0.0-12.20) |

6(0.20-13) |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

<0.001 |

|

%Eos |

2.5(0.10-22.50) |

2.50(0.20-24.30) |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

<0.001 |

|

%Bas |

0.65(0.20-3.10) |

0.50(0.10-2.20) |

0.50(0.10-1.50) |

<0.001 |

|

Neu |

4.92(0.94-24.31) |

4.40(0.99-21.68) |

4.65(0.78-23.96) |

0.015 |

|

Lymph |

2.41(0.39-5.76) |

2.31(0.37-5.40) |

2.49(0.45-5.99) |

0.049 |

|

Mon |

0.15(0.00-0.93) |

0.43(0.01-1.06) |

0.49(0.05-1.17) |

<0.001 |

|

Eos |

0.20(0.01-2.08) |

0.18(0.01-2.19) |

0.16(0.01-2.55) |

0.730 |

|

Bas |

0.05(0.01-0.23) |

0.04(0.01-0.17) |

0.04(0.01-0.13) |

<0.001 |

|

RBC |

5.12(2.47-7.65) |

4.62(2.21-6.35) |

5.13(2.48-7.05) |

<0.001 |

|

HGB |

14.2(6.90-21.30) |

12.6(6.20-16.9) |

14.10(6.90-18.20) |

<0.001 |

|

HCT |

43.15(21.4-64.8) |

38.90(19-51.20) |

43.45(3.72-54.60) |

<0.001 |

|

MCV |

85.45(56.90-108.5) |

85.15(56.8-108.4) |

85.9(57.3-108.6) |

0.534 |

|

MCH |

28.4(18.10-35.70) |

28.10(18-37.5) |

28.25(18.10-36.40) |

0.425 |

|

MCHC |

33(30.50-37.60) |

32.70(30.4-39.10) |

32.60(30-38.40) |

<0.001 |

|

RDW-SD |

43.5(34.70-63.10) |

43.40(34.60-64.00) |

44.10(35.30-82.20) |

0.016 |

|

PLT |

159(32-424) |

176(21-1584) |

250(86-482) |

<0.001 |

|

MPV |

9.30(6.90-12.10) |

8.80(4.40-11.80) |

9.10(7.10-13.00) |

<0.001 |

|

PDW |

11.85(7.30-21.10) |

11.10(2.60-20.00) |

11.60(8.10-23.60) |

<0.001 |

|

PCT |

0.15(0.03-0.34) |

0.15(0.02-0.70) |

0.22(0.09-0.37) |

<0.001 |

|

PLCR |

31.75(15.30-51.10) |

28.15(5.20-48.80) |

30.40(15.40-57.90) |

<0.001 |

Regarding variation in estimation of CBC parameters using the results of two anticoagulated blood such as K2EDTA-sodium citrate, K2EDTA-sodium heparin, sodium citrate-sodium heparin, the results of the comparison of K2EDTA-sodium citrate indicated comparable results in median %Neu, %Lymph, %Eos, Neu, Bas, MCV, MCH, and MCHC with a p-value of ≥0.05. Comparison of K2EDTA-sodium heparin results indicated comparable results in median WBC, %Lymph, %Eos, Neu, Lymph, RBC, HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, RDW-SD, MPV, PDW, and PLCR with a p-value of ≥0.05. In comparing the results of CBC between sodium citrate-sodium heparin, the result indicated a nonsignificant difference in median WBC, %Lymph, %Eos, Lymph, MCV, MCH, RDW-SD, and PCT (Table 4).

|

CBC parameters |

Sodium Citrate |

Sodium Heparin |

P-value |

K2EDTA |

Sodium Heparin |

P-value |

K2EDTA |

Sodium Citrate |

P-value |

|

WBC |

7.21(2.26-23.85) |

7.54(2.52-26.26) |

0.121 |

7.51(2.54-26.10) |

7.54(2.52-26.26) |

0.941 |

7.51(2.54-26.10) |

7.21(2.26-23.85 |

0.05 |

|

%Neu |

56.70(37.60-90.90) |

61.15(37.2-92.6) |

<0.001 |

56.30(30.70-91.80) |

61.15(37.2-92.6) |

<0.001 |

56.30(30.70-91.80) |

56.70(37.60-90.90) |

0.788 |

|

%Lymph |

33.55(4-50.50) |

33.2(3.8-50.30) |

0.922 |

33.45(3.90-52.60) |

33.2(3.8-50.30) |

0.695 |

33.45(3.90-52.60) |

33.55(4-50.50) |

0.903 |

|

%Mon |

6(0.20-13) |

1.9(0.0-12.20) |

<0.001 |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

1.9(0.0-12.20) |

<0.001 |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

6(0.20-13) |

0.003 |

|

%Eos |

2.50(0.20-24.30) |

2.5(0.10-22.50) |

0.801 |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

2.5(0.10-22.50) |

0.994 |

6.45(0.80-14.10) |

2.50(0.20-24.30) |

0.740 |

|

%Bas |

0.50(0.10-2.20) |

0.65(0.20-3.10) |

<0.001 |

0.50(0.10-1.50) |

0.65(0.20-3.10) |

<0.001 |

0.50(0.10-1.50) |

0.50(0.10-2.20) |

0.07 |

|

Neu |

4.92(0.94-24.31) |

4.92(0.94-24.31) |

0.011 |

4.65(0.78-23.96) |

4.92(0.94-24.31) |

0.288 |

4.65(0.78-23.96) |

4.92(0.94-24.31) |

0.345 |

|

Lymph |

2.41(0.39-5.76) |

2.41(0.39-5.76) |

0.282 |

2.49(0.45-5.99) |

2.41(0.39-5.76) |

0.633 |

2.49(0.45-5.99) |

2.41(0.39-5.76) |

0.040 |

|

Mon |

0.15(0.00-0.93) |

0.15(0.00-0.93) |

<0.001 |

0.49(0.05-1.17) |

0.15(0.00-0.93) |

<0.001 |

0.49(0.05-1.17) |

0.15(0.00-0.93) |

<0.001 |

|

Eos |

0.20(0.01-2.08) |

0.20(0.01-2.08) |

<0.001 |

0.16(0.01-2.55) |

0.20(0.01-2.08) |

<0.001 |

0.16(0.01-2.55) |

0.20(0.01-2.08) |

<0.001 |

|

Bas |

0.05(0.01-0.23) |

0.05(0.01-0.23) |

<0.001 |

0.04(0.01-0.13) |

0.05(0.01-0.23) |

<0.001 |

0.04(0.01-0.13) |

0.05(0.01-0.23) |

0.547 |

|

RBC |

5.12(2.47-7.65) |

5.12(2.47-7.65) |

<0.001 |

5.13(2.48-7.05) |

5.12(2.47-7.65) |

0.993 |

5.13(2.48-7.05) |

5.12(2.47-7.65) |

<0.001 |

|

HGB |

14.2(6.90-21.30) |

14.2(6.90-21.30) |

<0.001 |

14.10(6.90-18.20) |

14.2(6.90-21.30) |

0.816 |

14.10(6.90-18.20) |

14.2(6.90-21.30) |

<0.001 |

|

HCT |

43.15(21.4-64.8) |

43.15(21.4-64.8) |

<0.001 |

43.45(3.72-54.60) |

43.15(21.4-64.8) |

0.999 |

43.45(3.72-54.60) |

43.15(21.4-64.8) |

<0.001 |

|

MCV |

85.45(56.90-108.5) |

85.45(56.90-108.5) |

0.874 |

85.9(57.3-108.6) |

85.45(56.90-108.5) |

0.808 |

85.9(57.3-108.6) |

85.45(56.90-108.5) |

0.503 |

|

MCH |

28.4(18.10-35.70) |

28.4(18.10-35.70) |

0.391 |

28.25(18.10-36.40) |

28.4(18.10-35.70) |

0.773 |

28.25(18.10-36.40) |

28.4(18.10-35.70) |

0.807 |

|

MCHC |

33(30.50-37.60) |

33(30.50-37.60) |

0.009 |

32.60(30-38.40) |

33(30.50-37.60) |

<0.001 |

32.60(30-38.40) |

33(30.50-37.60) |

0.502 |

|

RDW-SD |

43.5(34.70-63.10) |

43.5(34.70-63.10) |

0.709 |

44.10(35.30-82.20) |

43.5(34.70-63.10) |

0.110 |

44.10(35.30-82.20) |

43.5(34.70-63.10) |

0.014 |

|

PLT |

159(32-424) |

159(32-424) |

0.001 |

250(86-482) |

159(32-424) |

<0.001 |

250(86-482) |

159(32-424) |

<0.001 |

|

MPV |

9.30(6.90-12.10) |

9.30(6.90-12.10) |

<0.001 |

9.10(7.10-13.00) |

9.30(6.90-12.10) |

0.211 |

9.10(7.10-13.00) |

9.30(6.90-12.10) |

<0.001 |

|

PDW |

11.85(7.30-21.10) |

11.85(7.30-21.10) |

<0.001 |

11.60(8.10-23.60) |

11.85(7.30-21.10) |

0.207 |

11.60(8.10-23.60) |

11.85(7.30-21.10) |

0.019 |

|

PCT |

0.15(0.03-0.34) |

0.15(0.03-0.34) |

0.022 |

0.22(0.09-0.37) |

0.15(0.03-0.34) |

<0.001 |

0.22(0.09-0.37) |

0.15(0.03-0.34) |

<0.001 |

|

PLCR |

31.75(15.30-51.10) |

31.75(15.30-51.10) |

<0.001 |

30.40(15.40-57.90) |

31.75(15.30-51.10) |

0.143 |

30.40(15.40-57.90) |

31.75(15.30-51.10) |

0.001 |

The agreement levels between different anticoagulants, using K2EDTA as the standard, were evaluated. Sodium citrate showed perfect agreement in assessing MCV and MCH (CCC = 0.990) but displayed significant agreement in determining WBC, %Neu, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, and Eos (CCC between 0.95 and 0.99). Moderate agreement was observed in assessing MCHC (CCC = 0.929), while poor agreement was found in all other parameters with CCC<0.90. Similarly, sodium heparin demonstrated perfect agreement in determining MCV (CCC=0.994) and MCH (CCC=0.990), with substantial agreement in other parameters such as WBC, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, RBC, and HGB (CCC between 0.95 and 0.99), but poor agreement in parameters with CCC<0.90. Regarding the comparison of K2EDTA and sodium citrate, citrate was highly precise and accurate in the estimation of WBC, %Neu, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, Eos, MCV, MCH, and MCHC. While comparing sodium heparin to K2EDTA, it was highly precise in the estimation of WBC, %Neu, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, Eos, RBC, HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC, and PLCR (Table 5).

|

CBC parameters |

K2EDTA-Citrate |

Pearson ρ (precision) |

Accuracy |

K2EDTA-Sodium heparin |

Pearson ρ (precision) |

Accuracy |

|

WBC |

0.97(0.9571 -0.9718) |

0.988 |

0.977 |

0.985(0.981- 0.989) |

0.986 |

0.999 |

|

%Neu |

0.972(0.964-0.978) |

0.974 |

0.998 |

0.847(0.814-0.875) |

0.925 |

0.916 |

|

%Lymph |

0.984(0.980- 0.988) |

0.985 |

0.999 |

0.951(0.937- 0.961) |

0.954 |

0.997 |

|

%Mon |

0.663(0.593 - 0.723) |

0.705

|

0.941 |

0.157(0.111 -0.201) |

0.440 |

0.355 |

|

%Eos |

0.636(0.567 - 0.697) |

0.688 |

0.926 |

0.594(0.525 - 0.656) |

0.675 |

0.881 |

|

%Bas |

0.460(0.361 -0.548) |

0.480 |

0.958 |

0.305(0.209 - 0.396) |

0.371 |

0.822 |

|

Neu |

0.980(0.975 - 0.984) |

0.990 |

0.990 |

0.972(0.964 - 0.978) |

0.980 |

0.991 |

|

Lymph |

0.956(0.949 - 0.966) |

0.984 |

0.974 |

0.969(0.961 - 0.976) |

0.973 |

0.997 |

|

Mon |

0.733(0.675 - 0.782) |

0.795 |

0.922 |

0.209(0.157 - 0.261) |

0.500 |

0.419 |

|

Eos |

0.968(0.960 - 0.975) |

0.973 |

0.995 |

0.927(0.909 - 0.941) |

0.942 |

0.983 |

|

Bas |

0.565(0.477 - 0.642) |

0.576 |

0.990 |

0.458(0.371 -0.537) |

0.543 |

0.848 |

|

RBC |

0.723(0.691 - 0.764) |

0.983 |

0.742 |

0.973(0.966-0.979) |

0.974 |

0.999 |

|

HGB |

0.742(0.705 - 0.775) |

0.988 |

0.752 |

0.977(0.971 - 0.982) |

0.979 |

0.998 |

|

HCT |

0.670(0.620 - 0.714) |

0.911 |

0.735 |

0.907(0.882 - 0.926) |

0.909 |

0.998 |

|

MCV |

0.990(0.987 - 0.992) |

0.995 |

0.995 |

0.994(0.992 - 0.995) |

0.995 |

0.998 |

|

MCH |

0.990(0.987 - 0.992) |

0.991 |

0.998 |

0.990(0.987 - 0.992) |

0.992 |

0.998 |

|

MCHC |

0.929(0.910 - 0.944) |

0.933 |

0.995 |

0.874(0.844 - 0.898) |

0.932 |

0.937 |

|

RDW-SD |

0.721(0.661 - 0.772) |

0.762 |

0.946 |

0.738(0.681- 0.786) |

0.771 |

0.958 |

|

PLT |

0.313(0.236 - 0.386) |

0.470 |

0.668 |

0.290(0.235 - 0.343) |

0.648 |

0.448 |

|

MPV |

0.784(0.734 - 0.826) |

0.830 |

0.945 |

0.873(0.841 - 0.899) |

0.887 |

0.985 |

|

PDW |

0.790(0.740 - 0.832) |

0.815 |

0.970 |

0.819(0.774 - 0.856) |

0.832 |

0.983 |

|

PCT |

0.319(0.256 - 0.380) |

0.598 |

0.534 |

0.238(0.187- 0.289) |

0.585 |

0.408 |

|

PLCR |

0.833(0.794- 0.866) |

0.879 |

0.948 |

0.876(0.847- 0.901) |

0.901 |

0.973 |

Discussion

The choice of anticoagulants and storage time significantly affect blood sample analysis [10]. In a study by Akorsu et al. involving 55 healthy individuals, consistency in blood parameters across three anticoagulants was observed: K3EDTA, sodium citrate, and lithium heparin [3]. Similarly, a current study utilized K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin, finding excellent consistency in various blood parameters, with ICC values exceeding 0.90.

Regarding variation in CBC parameters using different anticoagulants, in a study which is conducted on 30 clinically healthy dogs from different breeds, no significant variation between sodium citrate and K3EDTA was found in 4 out of 8 CBC parameters (50%) including HGB, HCT, PLT, and PCT [11]. Similarly, in a study conducted on humans, in which variation in the estimation of CBC parameters was evaluated using three different anticoagulants, namely, K3EDTA, sodium citrate, and lithium heparin, no statistically significant difference was observed in 5 out of 14 CBC parameters (35.7%) including MCV, MCH, MCHC, %Lymph, and %Neu among the three anticoagulants examined [3]. In the present study, regarding variation in CBC parameters using K2EDTA, sodium citrate, and sodium heparin, no statistically significant variation was found in 4 out of 23 CBC parameters (17.40%) including %Lymph, Eos, MCV, and MCH among these three different anticoagulants. The significant variations observed in other CBC parameters underscore the need for careful consideration when selecting anticoagulants, particularly in clinical settings where precise and consistent CBC measurements are crucial for accurate diagnosis and monitoring of conditions [12].

In a study of 50 healthy dogs comparing EDTA and sodium citrate, no comparable results were found among 9 CBC parameters, suggesting citrate may lead to inaccurate results compared to EDTA [13]. Another study of 55 healthy individuals comparing heparin and citrate revealed significant differences in 5 out of 14 CBC parameters (35.71%), with the remaining parameters showing variations. Similar patterns were observed when comparing citrate to EDTA. Comparing heparin to K3EDTA showed significant variations in three parameters (21.43%) [3]. In the current study, comparing K2EDTA to sodium citrate showed similar results in 8 out of 23 CBC parameters (34.78%), while comparing K2EDTA to sodium heparin showed comparable values in 14 out of 23 CBC parameters (60.87%).

Comparing PLT results between K2EDTA and sodium citrate with sodium heparin, significantly lower PLT counts were found in the latter two in the current study, contradicting findings in existing genuine literature [14-16]. One study suggested that citrate's strong platelet activation in sick animals may lead to decreased PLT counts due to platelet clumping [17]. Additionally, lower HGB and HCT values were observed in citrated blood samples compared to EDTA, consistent with previous studies [3,11]. This discrepancy may be attributed to citrate's interference with HGB oxidation, resulting in higher HGB levels in EDTA samples.

The CBC is commonly conducted on venous blood specimens anticoagulated with EDTA. Among various EDTA subtypes, the dipotassium salt form, K2EDTA, is endorsed by the International Council for Standardization in Hematology as the preferred anticoagulant for blood cell enumeration and sizing [7]. The study evaluated agreement levels between different anticoagulants, using K2EDTA as the standard. Sodium citrate showed substantial agreement in 8 out of 23 CBC parameters (34.78%), including MCV, MCH, WBC, %Neu, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, and Eos. Similarly, sodium heparin demonstrated substantial agreement in determining MCV, MCH, WBC, %Lymph, Neu, Lymph, RBC, and HGB. These findings align with previous literature, which indicated substantial agreement with heparin in assessing 4 out of 14 CBC parameters (28.57%), including RBC, HGB, HCT, and MCH [3].

Conclusion

Citrate was found to be a less reliable anticoagulant for CBC estimation compared to K2EDTA, potentially leading to inaccurate readings. On the other hand, sodium heparin showed comparable performance to K2EDTA, making it a suitable alternative under specific conditions.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and utilized data obtained from hospital archives Ethical Approval for this study was obtained from the Ksciens ethical committee (Approval Number 43. 2025).

Patient consent (participation and publication): Written informed consent was obtained from all patients (or their legal guardians, where applicable) for participation in the study and for the publication of all associated clinical information and images.

Source of Funding: Star Lab Company.

Role of Funder: The funder remained independent, refraining from involvement in data collection, analysis, or result formulation, ensuring unbiased research free from external influence.

Acknowledgements: Not applicable.

Authors' contributions: RQS and SQO were major contributors to the conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for related studies. DAH and AMM were involved in the literature review and the writing of the manuscript. SLE, HAY, HSA and MTT were involved in the literature review, the design of the study, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the processing of the tables. QOS and AMM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Use of AI: AI was not used in the drafting of the manuscript, the production of graphical elements, or the collection and analysis of data.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Exploring the Efficacy of Once and Twice Weekly Thyroxine Dosing: A Promising Approach for Hypothyroidism Management

Abdulwahid M. Salih, Aso S. Muhialdeen, Mohsin M. Ahmed, Hardi M. Zahir, Yadgar A. Saeed,...

Abstract

Introduction

Hypothyroidism is a common endocrine disorder, in which the management involves daily intake of thyroxine. However, adherence to a daily medication regimen poses a substantial challenge for many patients. The current study aims to assess the efficacy of once and twice-weekly thyroxine regimen for the management of hypothyroidism.

Methods

This was a single-center cohort study involving hypothyroid patients that was conducted over three years. In this study, standard daily, once and twice-weekly thyroxine dosing regimens were used to treat the patients. The effectiveness of the three dosage regimens was ascertained by whether the patients achieved a euthyroid state after six months of therapy.

Results

In total, 328 hypothyroid cases due to thyroiditis were included in this study. The average age of the cases was 42.7 years (14-92). Before thyroxine therapy, in the standard daily regimen group, the median level of TSH was 15.4 μIU/mL (IQR 23.1), in the once-weekly regimen group, the level was 9.2 μIU/mL (IQR 6.8), and in the twice-weekly regimen group, the level was 9.1 μIU/mL (IQR 7.3). After thyroxine intake and upon follow-up after 6 months, the TSH level decreased to 4.0 μIU/mL (IQR 3.7), 4.5 μIU/mL (IQR 4.9) and 4.2 μIU/mL (IQR 5.1) in the standard daily, once- and twice-weekly regimen groups, respectively.

Conclusion

Once and twice weekly thyroxine shows promise as strategies for managing hypothyroidism. However, variability in patients in response to weekly thyroxine needs to be taken into account.

Introduction

Hypothyroidism is a condition characterized by the inadequate production of thyroid hormones and represents a common endocrine disorder affecting a significant proportion of the global population [1]. The standard management of this condition typically involves daily administration of synthetic thyroxine to normalize thyroid hormone levels, thereby alleviating associated symptoms and metabolic disturbances. Daily thyroxine therapy regimen is well-established in clinical practice, with its efficacy extensively documented in the medical literature [1,2]. However, adherence to a daily medication regimen can be challenging for many patients. Factors such as the requirement to take the medication on an empty stomach, the necessary waiting period before the next meals or beverages, and potential drug interactions may contribute to inconsistent compliance. Suboptimal adherence to daily thyroxine therapy can significantly impair the management of hypothyroidism, resulting in inadequate control of thyroid function and poorer patient outcomes [3].

Recently, non-daily alternative dosing schedules, specifically once or twice-weekly thyroxine administration, have gained attention as potential strategies to improve adherence. Nevertheless, studies evaluating the efficacy of these regimens remain limited, and current evidence is insufficient to support changes in clinical practice. The current study aims to assess the efficacy of once and twice-weekly thyroxine dosing compared to standard daily administration for the management of hypothyroidism.

Methods

Study design

This was a single-center cohort study conducted at the head and neck center of Smart Health Tower, Sulaimani, Iraq, from January 2020 to January 2023. It involved the retrospective analysis of a series of hypothyroid cases to evaluate the efficacy of once and twice-weekly thyroxine regimens compared to standard daily dose. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and the family of the patients.

Participation

Participants were individuals who visited the head and neck center for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Patients who had undergone thyroidectomy were excluded from the study to avoid confounding effects on thyroid function.

Treatment plan

Patients were assigned to one of three treatment groups based on the prescribed thyroxine regimen: daily, once-weekly, or twice-weekly. According to thyroid function tests and body weight, different daily and weekly doses were prescribed to the patients to reach euthyroidism, including 25, 50, 75, or 100 μg per day, or 100, 200, or 300 μg per week. Patients were followed for six months, and treatment effectiveness was determined by whether they achieved a euthyroid state, defined as a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level between 0.4 and 4.2 μIU/mL.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted from the center’s medical database and included patient’s age, gender, marital status, occupation, chief complaint, thyroxine dosage, TSH pre-treatment, and TSH six months following therapy. All data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (2016). Statistical analyses were performed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 25. Descriptive statistics were presented as means or medians (for non-normally distributed data), counts, and percentages. Univariate analyses were conducted to compare baseline characteristics (including age, gender, marital status, occupation, and chief complaint) and treatment outcomes between groups. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of achieving normal TSH (0.4–4.2 μIU/mL) at six months. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 328 hypothyroid cases due to thyroiditis were included in this study. The mean age of the cases was 42.7 years, ranging from 14 to 92 years. The majority of the cases were female, accounting for 303 individuals (92.4%). The most common presentation in all groups was weakness in 146 (44.5%) cases, followed by incidental finding in 81 (24.7%), and neck pain in 37 (11.3%). Overall, the first TSH mean (before therapy) was 20.8, while the second TSH mean (after treatment) was 5.1 (Table 1).

|

Characteristics |

Frequency/Mean |

Percentage/SD |

|

Age |

42.7 |

13.1 |

|

First TSH |

20.8 |

25.1 |

|

Second TSH |

5.1 |

4.2 |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male Female |

25 303 |

7.6 92.4 |

|

Occupation |

||

|

Employed Jobless Lawyer Student Teacher Others |

18 247 3 21 16 23 |

5.5 75.3 0.9 6.4 4.9 7 |

|

Marital Status |

||

|

Married Single |

283 43 2 |

86.3 13.1 0.6 |

|

Chief Complain |

||

|

Abnormal Menstruation Cold Intolerance Hair Loss Incidental Neck Pain Neck Swelling Neck Weakness Others |

19 6 5 81 37 18 146 16 |

5.8 1.8 1.5 24.7 11.3 5.5 44.5 4.6 |

|

Treatment |

||

|

1/week 2/week Daily |

100 119 109 |

30.5 36.3 33.2 |

| TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone, SD: Standard deviation | ||

The median age was similar across the three groups, with 42.0 years (IQR 13.5) in the once-weekly group, 40.0 years (IQR 16.0) in the twice-weekly group, and 43.0 years (IQR 23.0) in the daily group (p = 0.061). Females predominated in all groups, accounting for 98% of the once-weekly group, 97.5% of the twice-weekly group, and 81.7% of the daily group, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). Regarding occupation, the majority were jobless across all groups, but the daily group had a higher proportion of employed participants (9.2%) compared with the weekly groups (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

|

Variables |

Treatment |

P-value | ||

|

1/week (n=100) |

2/week (n=119) |

Daily (n=109) |

||

|

Age, median (IQR) |

42.0 (13.5) |

40.0 (16.0) |

43.0 (23.0) |

0.061 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

<0.001

|

|

Female |

98 (98.0%) |

116 (97.5%) |

89 (81.7%) |

|

|

Male |

2 (2.0%) |

3 (2.5%) |

20 (18.3%) |

|

|

Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

88 (88.0%) |

95 (79.8%) |

100(91.7%) |

0.012 |

|

Single |

10 (10.0%) |

24 (20.2%) |

9 (8.3%) |

|

|

Widow |

2 (2.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Chief Complain |

|

|

|

|

|

Abnormal Menstruation |

7 (7.0%) |

8 (6.7%) |

4 (3.7%) |

<0.001 |

|

Cold Intolerance |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (3.4%) |

2 (1.8%) |

|

|

Hair Loss |

2 (2.0%) |

1 (0.8%) |

2 (1.8%) |

|

|

Incidental |

5 (5.0%) |

6 (5.0%) |

70 (64.2%) |

|

|

Neck Pain |

15 (15.0%) |

17 (14.3%) |

5 (4.6%) |

|

|

Neck Swelling |

6 (6.0%) |

9 (7.6%) |

3 (2.8%) |

|

|

Neck Weakness |

59 (59.0%) |

69 (58.0%) |

18 (16.5%) |

|

|

Others |

6 (6.0%) |

5 (4.2%) |

5 (4.6%) |

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

Employed |

2 (2.0%) |

6 (5.0%) |

10 (9.2%) |

<0.001 |

|

Jobless |

79 (79%) |

92 (77.3%) |

76 (69.7%) |

|

|

Lawyer |

2 (2.0%) |

1 (0.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Student |

8 (8.0%) |

10 (8.4%) |

3 (2.8%) |

|

|

Teacher |

7 (7.0%) |

7 (5.9%) |

2 (1.8%) |

|

|

Others |

2 (2.0%) |

3 (2.5%) |

18 (16.5%) |

|

| IQR: Interquartile range | ||||

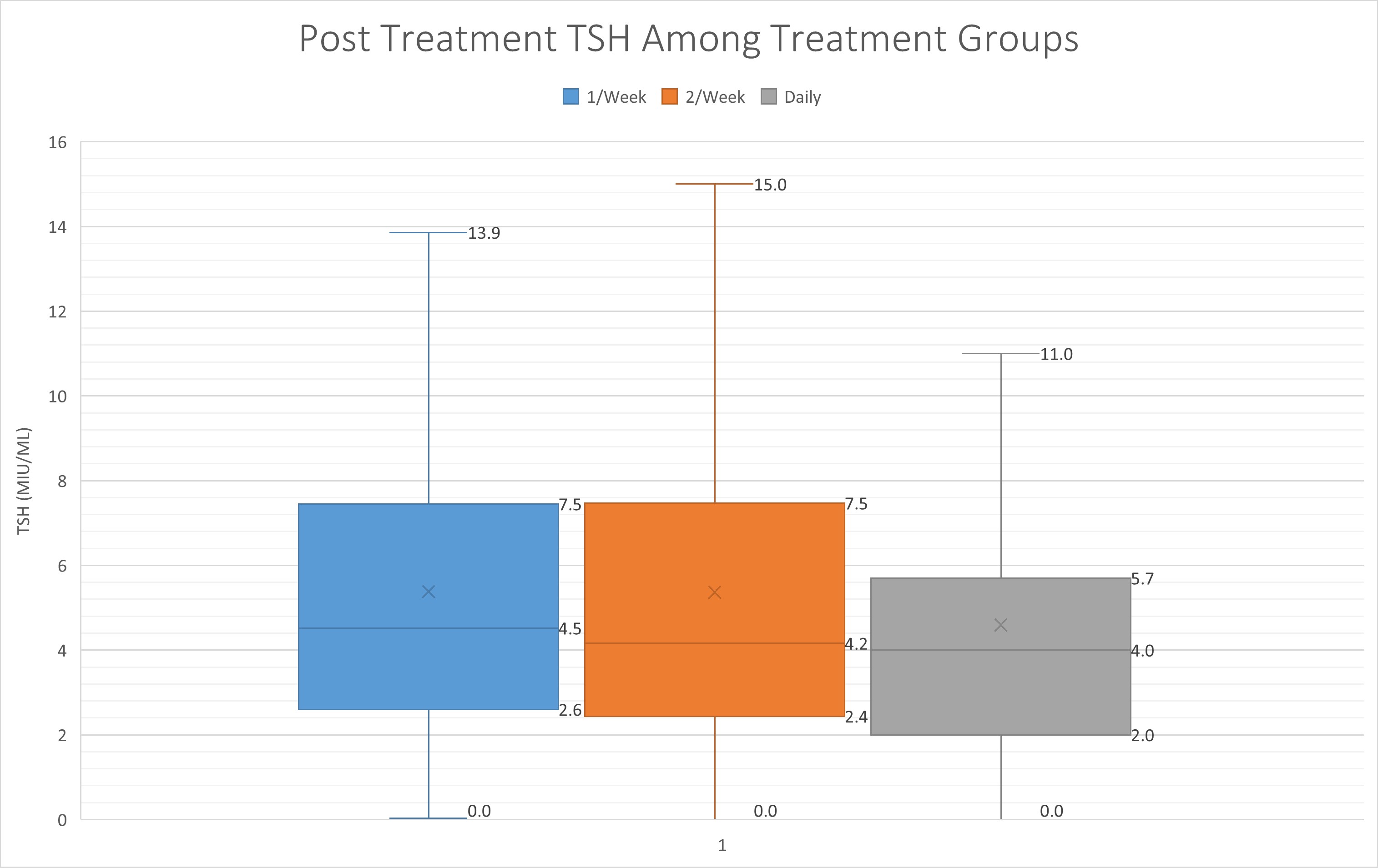

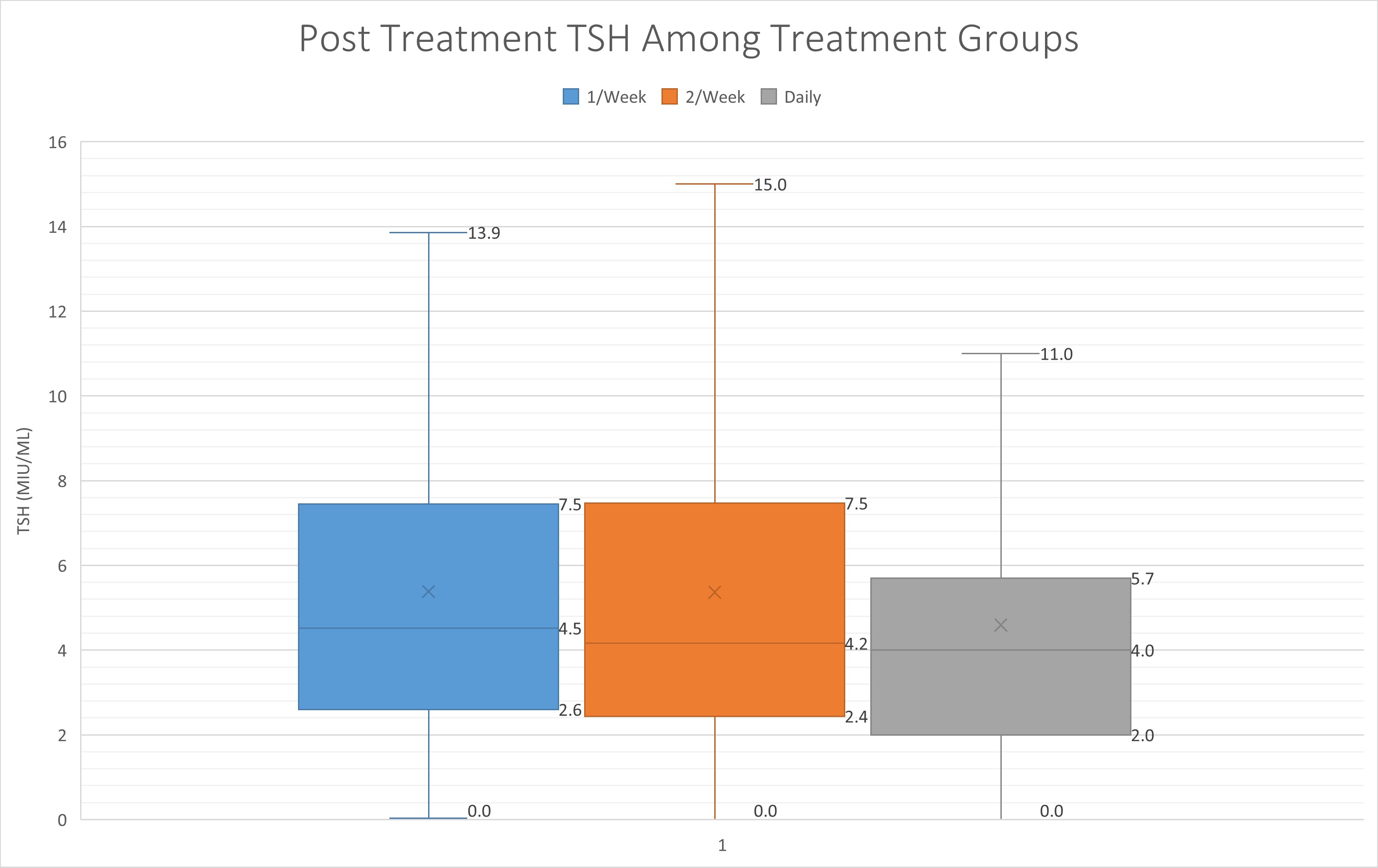

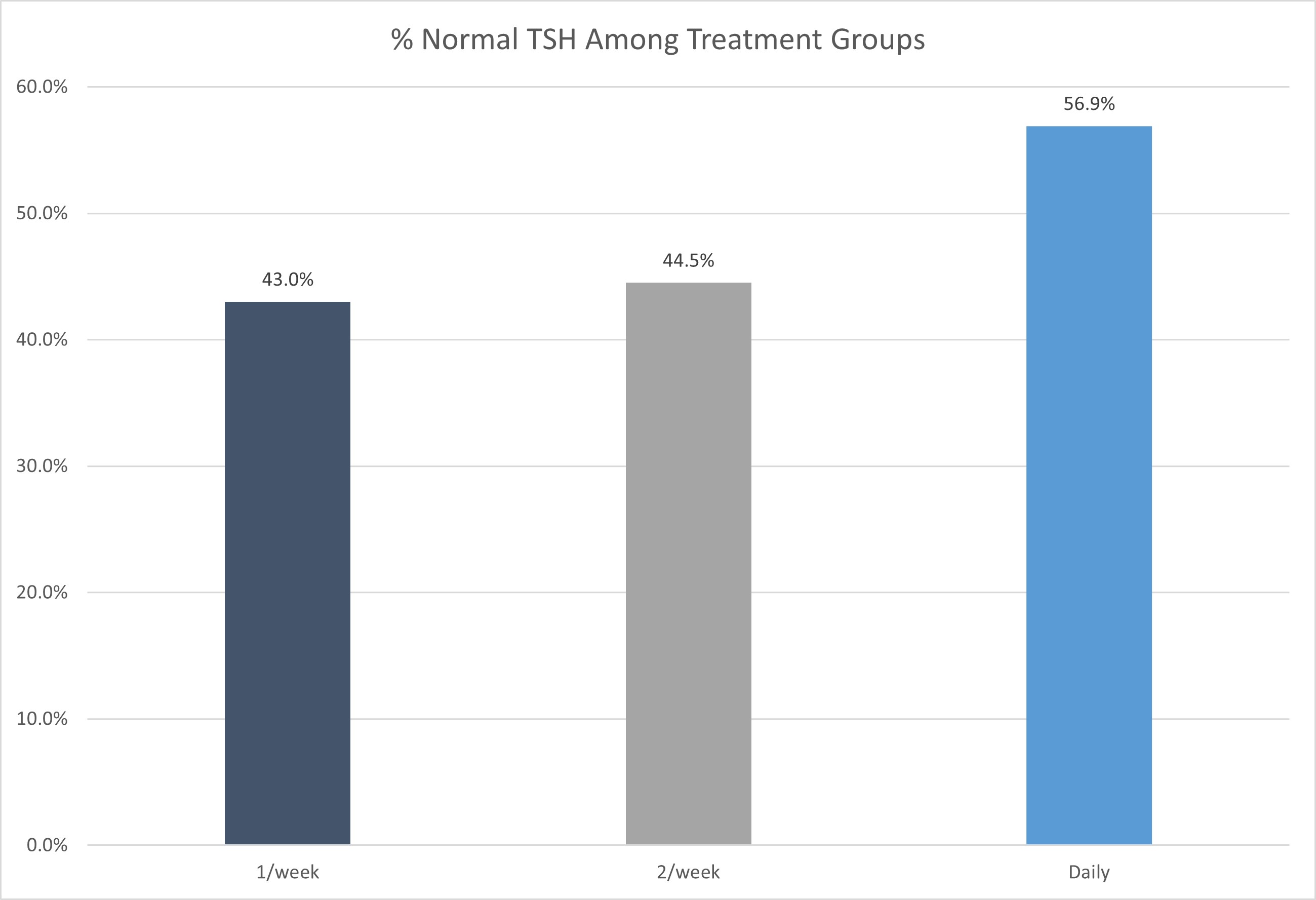

Before thyroxine therapy, in the once-weekly regimen group, the median value of TSH was 9.2 μIU/mL (IQR 6.8 μIU/mL), in the twice-weekly regimen group the level was 9.1 μIU/mL (IQR 7.3 μIU/mL), and in the standard daily dose group the median level was 15.4 (IQR 23.1 μIU/mL). After thyroxine intake and upon follow-up after six months, the TSH level decreased to 4.0 μIU/mL (IQR 3.7 μIU/mL), 4.2 μIU/mL (IQR 5.1 μIU/mL) and 4.5 μIU/mL (IQR 4.9 μIU/mL) in the standard daily, once- and twice-weekly regimen group, respectively (Figure 1) (Table 3). The outcome was statistically insignificant between groups. After six months of follow-up, 56.9% of patients in the daily regimen group, 43.0% in the once-weekly group, and 44.5% in the twice-weekly group achieved TSH levels within the normal reference range (Figure 2).

|

Variables |

Treatment |

P-value | ||

|

1/week (n=100) |

2/week (n=119) |

Daily (n=109) |

||

|

First TSH, median (IQR) |

9.2 (6.8) |

9.1 (7.3) |

15.4 (23.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Second TSH, median (IQR) |

4.5 (4.9) |

4.2 (5.1) |

4.0 (3.7) |

0.349 |

|

TSH Range |

|

|

|

|

|

<0.4 |

6 (6.0%) |

8 (6.7%) |

5 (4.6%) |

0.276 |

|

0.4 - 4.2 |

43 (43.0%) |

53 (44.5%) |

62 (56.9%) |

|

|

>4.2 |

51 (51.0%) |

58 (48.7%) |

42 (38.5%) |

|

| TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone, IQR: Interquartile range | ||||

Compared to the daily treatment group, patients in the once-weekly group had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.659 (95% CI: 0.310–1.398, p = 0.277), and those in the twice-weekly group had an OR of 0.763 (95% CI: 0.363–1.602, p = 0.474), indicating no statistically significant difference in achieving normal TSH between the treatment regimens. Gender was not a significant predictor; males had an OR of 1.845 (95% CI: 0.439–7.751, p =0.403) compared to females. Age and baseline TSH similarly did not significantly influence the likelihood of achieving normal TSH (OR = 0.997, p = 0.801 and OR = 0.995, p = 0.317, respectively) (Table 4).

|

Parameters |

B (S.E) |

Exp (B) (OR) |

95% CI |

P-value |

|

Treatment Group Daily* 1/week 2/week |

-0.418 (0.384) -0.271 (0.379) |

1 0.659 0.763 |

0.310-1.398 0.363-1.602 |

0.277 0.474 |

|

Age (Years) |

-0.003 (0.010) |

0.997 |

0.978-1.017 |

0.801 |

|

Gender Female* Male |

0.612 (0.732) |

1 1.845 |

0.439-7.751 |

0.403 |

|

First TSH |

-0.005 (0.005) |

0.995 |

0.985-1.005 |

0.317 |

|

Occupation Employed* Jobless Lawyer Student Teacher Others |

0.497 (0.568) 0.201 (1.367) 0.196 (0.795) 0.267 (0.758) -0.138 (0.788) |

1 1.643 1.223 1.217 1.306 0.871 |

0.540-5.002 0.084-17.827 0.256-5.780 0.296-5.770 0.186-4.084 |

0.382 0.883 0.805 0.724 0.861 |

|

Marital Status Married Single Widow |

-0.249 (0.434) 0.104 (1.496) |

1 0.779 1.109 |

0.333-1.825 0.059-20.814 |

0.566 0.945 |

Discussion

Hypothyroidism can often occur as a result of thyroiditis or thyroidectomy to remove part of or the entire thyroid tissue [4-6]. The standard treatment for hypothyroidism involves daily administration of thyroxine, a synthetic form of the thyroid hormone. However, emerging evidence suggests that a weekly thyroxine regimen may offer several advantages in terms of patient convenience, treatment adherence, and potentially improved clinical outcomes [7]. Noncompliance with thyroxine is the most prevalent cause of poor hypothyroidism management, which is linked to the discomfort of taking the drug when fasting, waiting 60 minutes for the next meal or beverage, and avoiding other medications that may interfere with thyroxine absorption [8]. The feasibility of weekly thyroxine dosing lies in the pharmacokinetics of levothyroxine. It has a long half-life, with stable levels maintained in the bloodstream for several weeks. Additionally, the availability of thyroxine formulations that allow for extended release further supports the feasibility of weekly dosing [9].

One of the primary advantages of weekly thyroxine is the potential for enhanced patient convenience and improved treatment adherence. Daily medication regimens can be challenging for patients to adhere to consistently, leading to suboptimal management of hypothyroidism. Weekly thyroxine simplifies the dosing schedule, reducing the burden of daily medication intake [10]. Studies have shown that non-adherence to daily thyroxine therapy is common and can result in inadequate control of thyroid function. By reducing the frequency of dosing, weekly thyroxine may address the issue of non-adherence and improve the effectiveness of treatment in achieving target thyroid hormone levels and overall clinical outcomes [11].

There have been very few studies comparing daily versus weekly treatment of thyroxine in hypothyroid patients globally. Therefore, there is a crucial need to expand the current body of litrerature on this treatment strategy. According to one study, in today's world of busy lifestyles, when it is difficult for patients to take thyroxine on a strict schedule, once-weekly thyroxine administration gives an alternate option for treating hypothyroidism, particularly in patients whose compliance is a big concern [12]. Bornschein et al. found comparable results between daily and weekly dosing, with no hyperthyroidism in patients with weekly regimens [10]. Rangan et al. demonstrated in a case series of two patients that once-weekly thyroxine is an alternate treatment approach for noncompliant patients and remarked that once-weekly thyroxine is a safe treatment regimen [11]. Another study found that when compared to a daily dosage of thyroxine, once weekly thyroxine is an effective and safe long-term treatment option for individuals with poor management of hypothyroidism or apparent thyroxine resistance. With directly monitored once-weekly thyroxine, approximately three-quarters of such individuals are able to achieve TSH normalization [8]. According to Chiu et al., weekly thyroxine administration results in less suppression and greater overall TSH levels while keeping below the normal reference range as specified by worldwide treatment recommendations. It may be a viable option for hypothyroid individuals, especially if compliance is an issue [13].

Concerns have also been expressed that taking a big dose of once-weekly thyroxine may result in increased supraphysiologic levels of thyroxine in the first few days, which may have an unfavorable effect on cardiovascular function. It is also believed that by the sixth day of thyroxine administration, the efficacy of once-weekly thyroxine would have worn off, resulting in the recurrence of hypothyroid symptoms and swings in TSH levels [14]. Grebe et al. showed that, while weekly treatment was well tolerated, thyroid function tests showed significant hypothyroidism with an increase in TSH and a decrease in thyroxine before the next weekly prescription [15]. A meta-analysis of four trials including 294 participants evaluated the effect of once weekly thyroxine on TSH after 6 weeks of treatment. After 6 weeks of therapy, once weekly thyroxine patients had considerably greater serum TSH than standard daily thyroxine patients [14]. The results of the current study showed that once weekly and twice weekly thyroxine were almost equally effective as standard daily thyroxine in achieving and maintaining normal thyroid function. There were no significant differences between the three treatment groups.

This study has several limitations, including relatively small group sizes, a single-center design, and a short follow-up period of six months. Despite these limitations, the findings provide supportive evidence that may have implications for current clinical practice regarding thyroxine administration. Future research involving larger, multicenter cohorts with longer follow-up periods is warranted to validate and expand upon these results.

Conclusion

The comparison of once-daily, once-weekly, and twice-weekly thyroxine administration highlights the potential benefits of less frequent dosing for hypothyroidism management. While all regimens appear to maintain comparable efficacy and safety, the convenience and potential for improved adherence associated with less frequent dosing regimens are notable. However, patient response to weekly thyroxine can vary, and some individuals may require more frequent administration or may not be suitable candidates for weekly therapy. Additionally, infrequent dosing carries the risk of missed doses, which could compromise treatment effectiveness. Therefore, close monitoring of thyroid function and individualized dose adjustments are essential to optimize outcomes. Long-term studies are needed to evaluate the sustained efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction with weekly thyroxine regimens. Further research comparing different thyroxine formulations for weekly dosing and assessing their impact on specific populations, such as pregnant women or patients with comorbidities, would be valuable.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study (Ethical Committee No: 95) was provided by the Ethical Committee of School of Medicine-University of Sulaimani.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their legal guardians for participation in this study and for the publication of any accompanying images, clinical information, and other data included in the manuscript.

Source of Funding: Smart Health Tower.

Role of Funder: The funder remained independent, refraining from involvement in data collection, analysis, or result formulation, ensuring unbiased research free from external influence.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: AMS and SFA were major contributors to the conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for related studies. MNH, SHH and HAH were involved in the literature review and the writing of the manuscript. ASM, MMA, HMZ, YAS, SHA, HOB, MAA and SHA were involved in the literature review, the design of the study, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the processing of the tables. AMS and MNH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Use of AI: AI was not used in the drafting of the manuscript, the production of graphical elements, or the collection and analysis of data.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

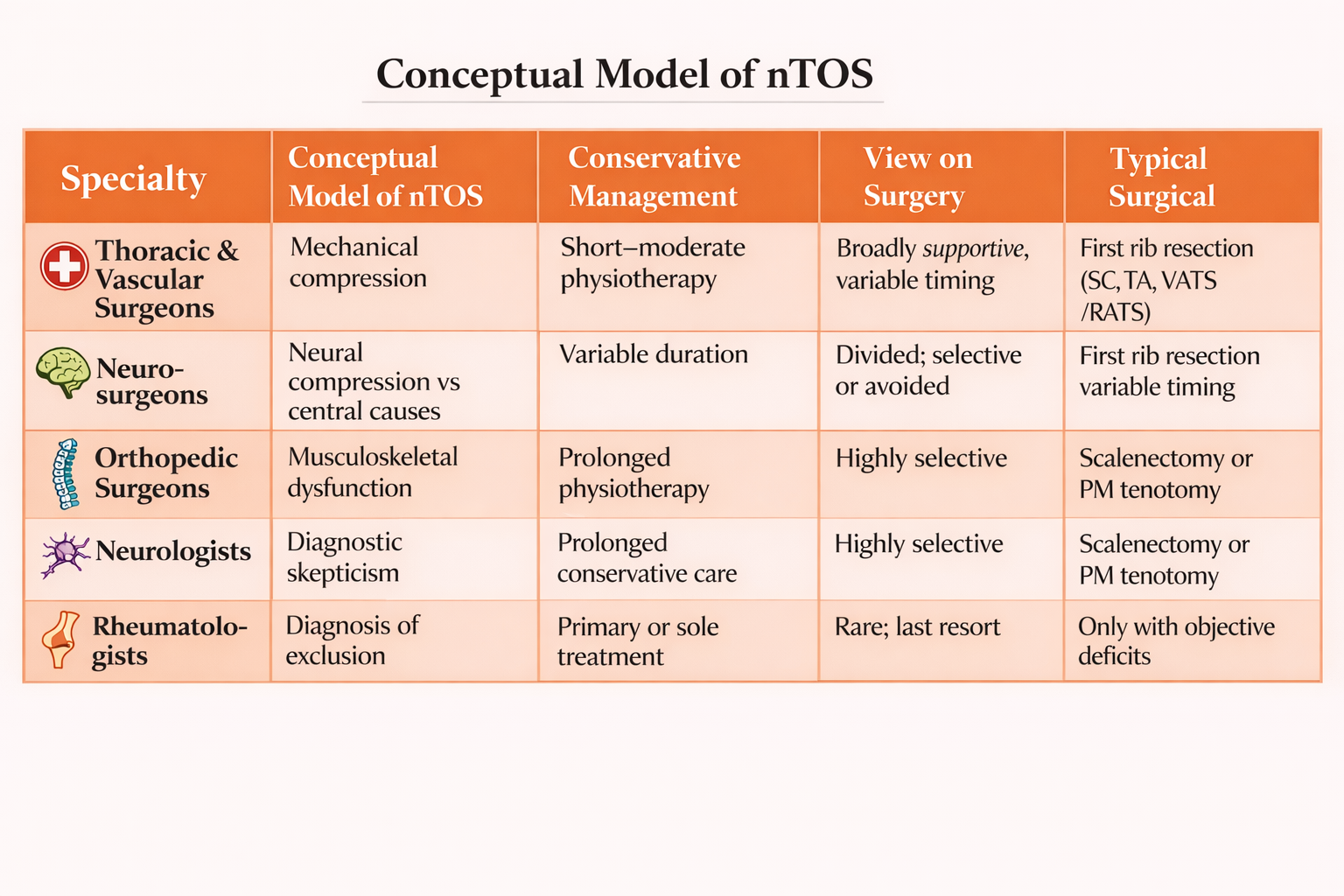

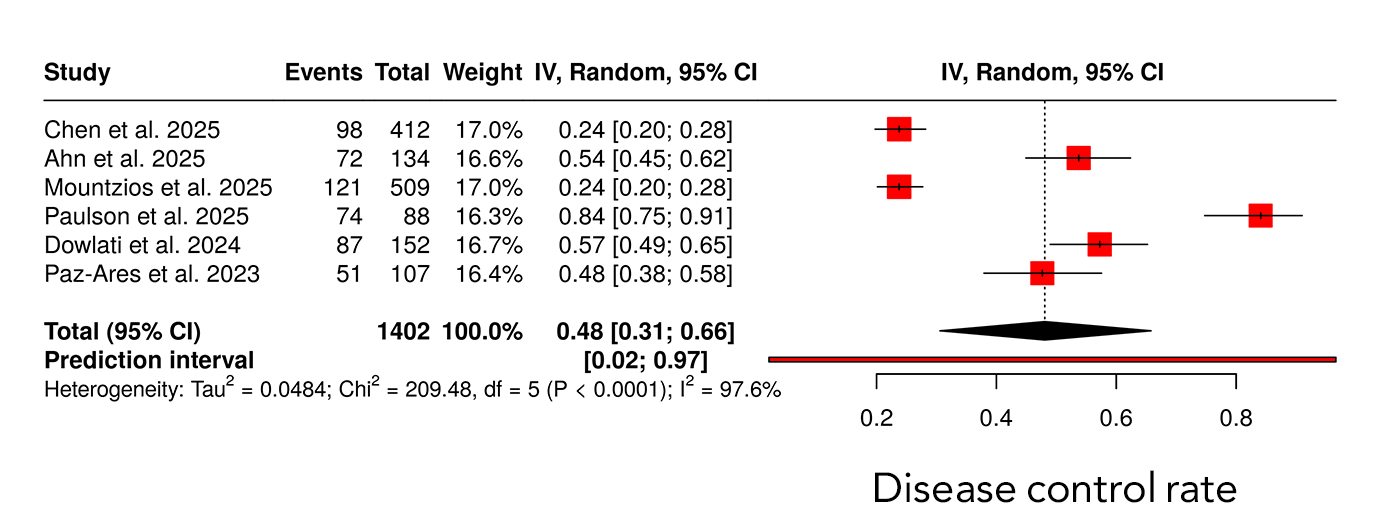

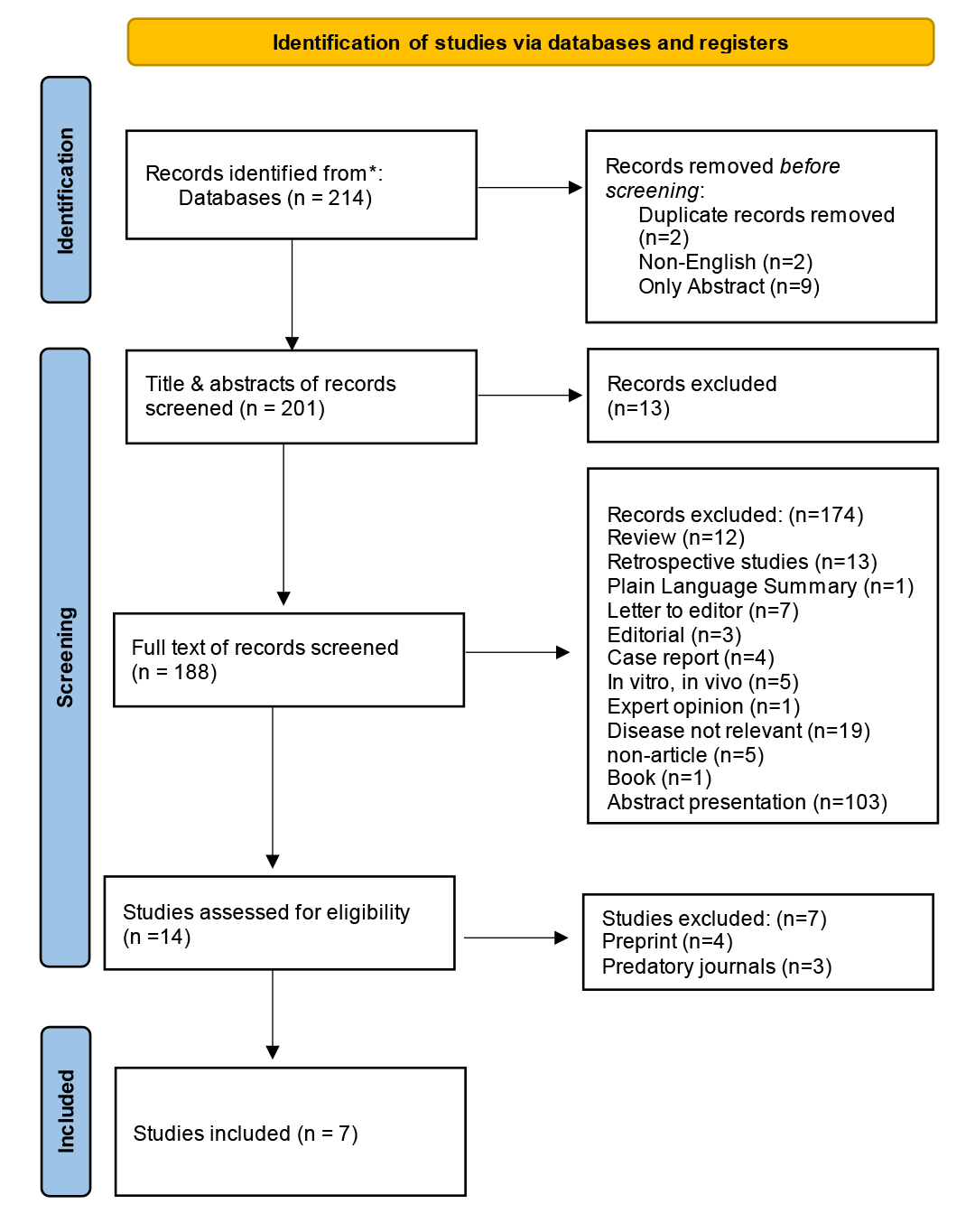

Suffering of Patients with Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS); The First Qualitative study in TOS

Fahmi H. Kakamad, Shvan H. Mohammed, Berun A. Abdalla, Saywan K. Asaad, Abdullah K. Ghafour,...

Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS) is hindered by symptom overlap with cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or psychosomatic disorders. This challenge is further compounded by often normal imaging and electrodiagnostic findings, resulting in prolonged diagnostic suffering encompassing emotional, financial, and social burdens.

Objectives

This first qualitative study explores narratives from 25 diagnosed women initially prescribed physiotherapy: (1) identify key themes related to diagnostic challenges; (2) examine the psychological and emotional impact of diagnostic delay; and (3) propose a patient-centered diagnostic framework.

Methods

Qualitative descriptive design using semi-structured interviews (20-30 minutes) with purposive sampling from a TOS clinic (inclusion: confirmed nTOS, >1-year symptoms, no prior surgery; Data saturation was achieved after 22 interviews). Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis generated 1,247 inductive codes, which were organized into four themes and twelve subthemes. NVivo software was used for data management. Member checking was conducted, and reporting followed COREQ guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained, and participant anonymity was preserved through pseudonyms.

Results

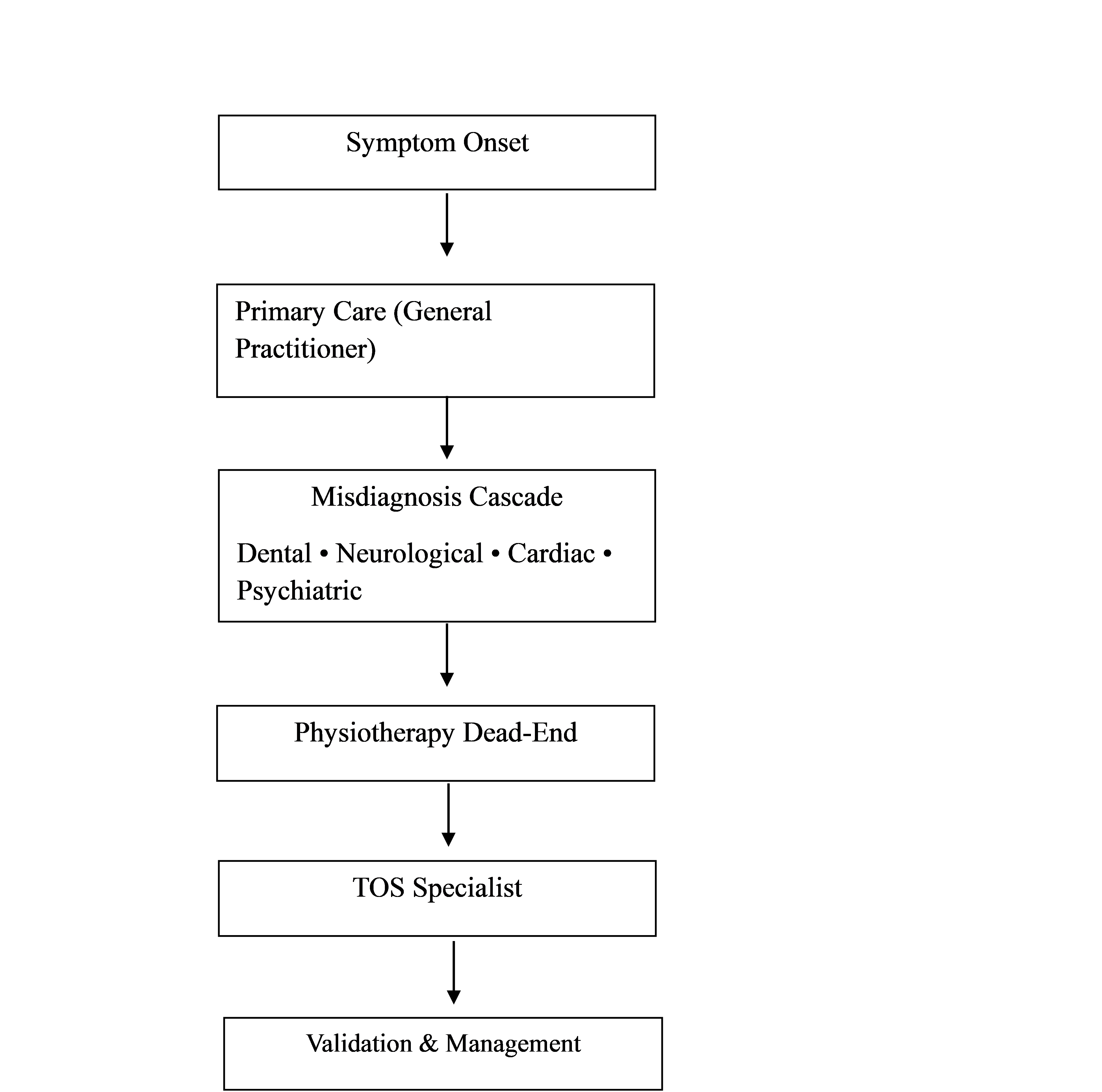

Four overarching themes emerged: (1) Fragmented Diagnostic Odyssey, characterized by multiple referrals (mean six clinicians per patient) and substantial out-of-pocket costs (USD 1,000–1,500); (2) Cascade of Misdiagnoses, including somatic mimics, invasive investigations, and prolonged incorrect treatment; (3) Social and Familial Invalidation, involving medical dismissal and pressure toward psychiatric explanations; and (4) Profound Emotional Suffering, with isolation and hopelessness identified in 84% of transcripts. A conceptual model was developed to illustrate the cumulative diagnostic journey.

Conclusion

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is associated with multilayered diagnostic and social invalidation consistent with the stigma of invisible illness. Improving outcomes requires enhanced clinician awareness of nTOS-specific red flags, validation of patient narratives, and multidisciplinary diagnostic pathways to reduce delays, prevent iatrogenic harm, and alleviate psychological distress.

Introduction

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS) is characterized by compression of the brachial plexus as it traverses the thoracic outlet, causing upper extremity pain, numbness, paresthesia, and variable degrees of weakness. The condition predominantly affects young women, often triggered by repetitive overhead activities, postural strain, or antecedent trauma. Despite its clinical relevance, nTOS remains one of the most diagnostically challenging peripheral nerve compression syndromes due to its heterogeneous and fluctuating presentation [1,2].

Clinical recognition is often delayed, as symptoms overlap substantially with more prevalent conditions such as cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, peripheral neuropathies, and functional or psychosomatic disorders. The absence of definitive radiological or electrodiagnostic findings in many patients further compounds diagnostic uncertainty, contributing to prolonged diagnostic latency that may span several years [1,2]. Consequently, patients frequently undergo multiple inconclusive investigations and consultations before receiving an accurate diagnosis [1,2].

Beyond physical morbidity, individuals with nTOS experience a form of diagnostic suffering, encompassing emotional distress, financial strain, social disruption, and erosion of trust in healthcare systems. Recurrent symptom invalidation and misattribution may intensify anxiety, frustration, and feelings of marginalization. This experience closely parallels Bury’s concept of biographical disruption in chronic illness, whereby delayed or contested diagnoses fracture personal identity, future planning, and the patient–clinician relationship [3,4].

The present study seeks to illuminate these underexplored qualitative dimensions through in-depth narratives from 25 diagnosed women, all of whom were initially prescribed physiotherapy as first-line management. The study objectives are threefold: (1) to identify recurring themes related to diagnostic challenges and healthcare encounters; (2) to explore the psychological and emotional impact of prolonged diagnostic trajectories; and (3) to propose a patient-centered diagnostic framework that integrates biomedical assessment with experiential and psychosocial dimensions.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative descriptive study design with interpretive orientation was employed using semi-structured conversations to explore participants lived experiences of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, this approach was selected to capture rich, first-person accounts while remaining close to participants’ language and meanings. The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [5].

Participants and sampling

Purposive sampling recruited 25 female patients from a TOS specialty clinic. Inclusion: confirmed nTOS diagnosis, physiotherapy as initial treatment, symptom duration >1 year. Exclusion: surgical intervention prior to study. Saturation achieved after 22 interviews, with 3 additional for confirmation. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a confirmed diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, (2) initiation of physiotherapy as first-line management, and (3) symptom duration exceeding one year. Patients who had undergone surgical intervention prior to study enrollment were excluded. Data saturation was reached after 22 interviews, with three additional interviews conducted to confirm thematic completeness and stability.

Data collection

One-on-one conversations (20–30 minutes) in a private clinic room to ensure confidentiality and participant comfort A semi-structured interview guide was used to explore diagnostic trajectories, experiences of misdiagnosis, emotional and psychological impact, and social responses to symptoms. Sample prompts included: “Can you walk me through your journey to receiving a diagnosis?” and “How did family members or healthcare providers respond to your symptoms?” (Table 1). All interview were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim, yielding approximately 450 pages of textual data.

|

Interview Guide Domains |

Sample Questions |

|

Diagnostic Journey |

"What tests did you undergo? How many specialists?" |

|

Misdiagnoses & Treatments |

"What alternative diagnoses were suggested?" |

|

Emotional/Social Impact |

"How did this affect your relationships or self-view?" |

|

Validation & Recovery |

"What changed after nTOS diagnosis?" |

Data analysis

Braun and Clarke's (2006) reflexive thematic analysis in six phases (6):

- Familiarization: Repeated, immersive reading of transcripts to gain an overall understanding of the data.

- Coding: Inductive line-by-line coding was performed, generating 1,247 initial codes.

- Theme Generation: Collating into 4 main themes, 12 subthemes.

- Review: Preliminary themes were reviewed and refined through member checking with ten participants.

- Definition: Themes were clearly defined, refined, and supported by illustrative patient quotations.

- Reporting: Final themes were synthesized and presented using verbatim extracts to preserve participants’ voices.

NVivo 14 used for management. Methodological rigor and trustworthiness were enhanced through maintenance of an audit trail, thick description, reflexive journaling, and transparency regarding researcher positioning; the researchers declared no personal or clinical conflicts of interest related to thoracic outlet syndrome.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for human research. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. Pseudonyms were assigned to protect confidentiality. Participants were provided with debriefing following the conversations and offered referral resources for psychological or clinical support if needed.

Results

Analysis of interviews with 25 participants (coded P1–P25) yielded four overarching themes, each comprising related subthemes supported by illustrative verbatim quotations.

Theme 1: Fragmented Diagnostic Odyssey

Participants described a prolonged and exhausting diagnostic trajectory characterized by repeated referrals and inconclusive investigations across multiple medical specialties. On average, participants reported consulting approximately six physicians prior to receiving a diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome.

Subtheme 1.1: Endless Investigations

"I have done hundreds of investigations; each doctor tells me a different diagnosis." (P7) "I cannot count how many doctors I visited; no one told me you have nTOS." (P14) These accounts highlight a cycle of uncertainty in which repeated testing failed to yield diagnostic closure.

Subtheme 1.2: Financial and Time Toll

The diagnostic delay was accompanied by substantial financial and temporal burden. Participants reported out-of-pocket expenditures ranging from approximately USD 1,000 to 1,500, in addition to lost workdays and prolonged functional impairment.

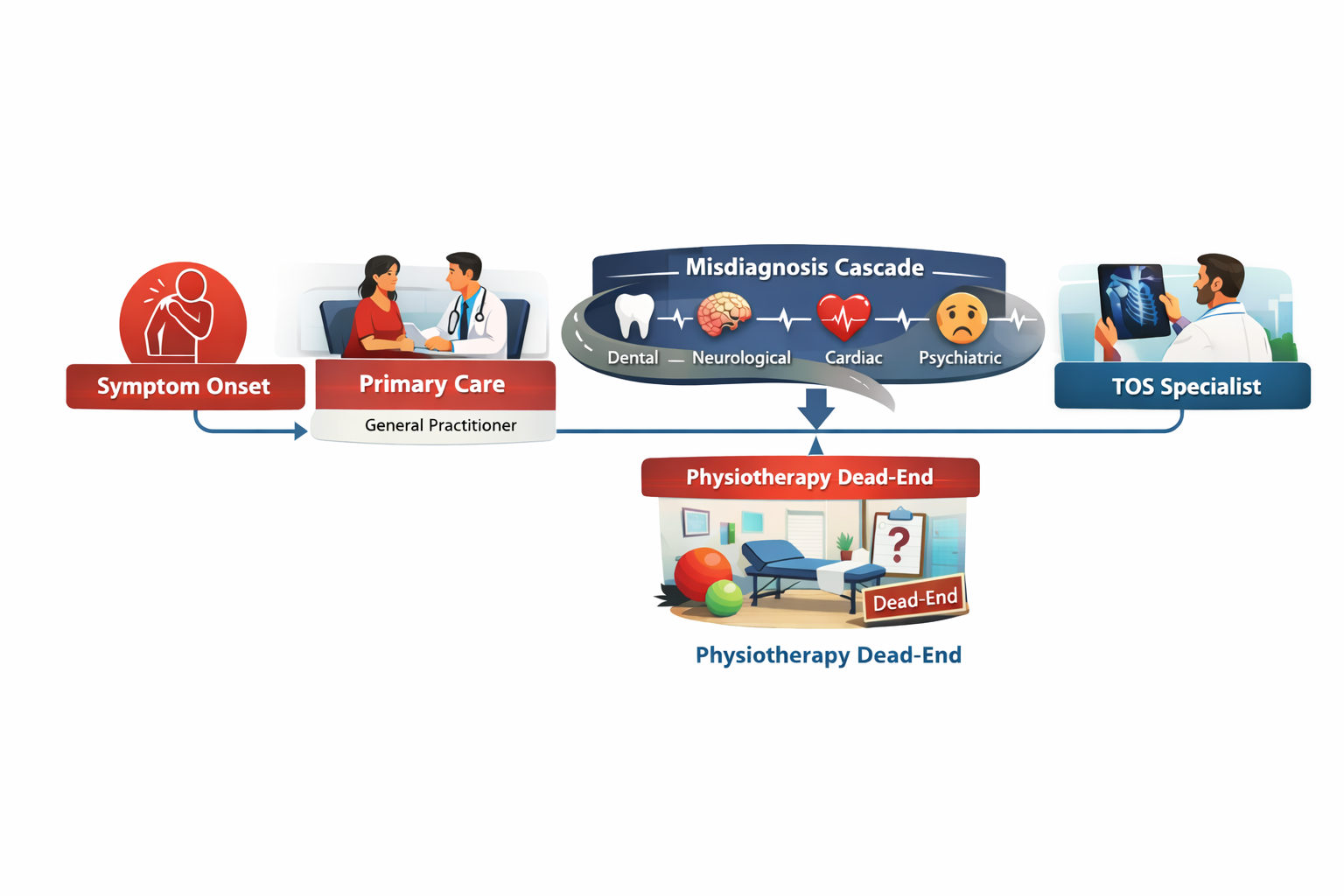

Theme 2: Cascade of Misdiagnoses