Small Cell Lung Cancer and Tarlatamab: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials

Abstract

Introduction

Tarlatamab is a Delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) -directed bispecific T-cell engager recently approved for use in patients with advanced small cell lung cancer (SCLC) after progression on platinum-based therapy. This meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of tarlatamab as monotherapy and in combination regimens in the treatment of SCLC.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines. PubMed/MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from inception through September 2025 to identify clinical trials evaluating tarlatamab in SCLC. Eligible studies reported quantifiable efficacy and/or safety outcomes. Random-effects models were used to pool objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR), and Kaplan–Meier methods were applied to assess survival outcomes.

Results

Seven clinical trials involving 1,247 patients with advanced SCLC were included. The pooled ORR was 0.42 (95% CI 0.31–0.54), with response rates ranging from 21–47% in monotherapy studies and up to 48% in combination regimens. Across six studies, pooled DCR was 0.48 (95% CI 0.31–0.66), with DCR reaching up to 87% in combination settings. Median progression-free survival ranged from 3.5 to 5.6 months, while median overall survival ranged from 13.2 to 25.3 months. Pooled time-to-event analyses demonstrated significant reductions in the risk of disease progression and death. Grade 3 and grade 4 adverse events occurred in 5.4% and 1.4% of patients, respectively, although safety reporting was incomplete in several studies.

Conclusion

Tarlatamab demonstrates clinically meaningful antitumor activity with an acceptable safety profile in heavily pretreated SCLC. These findings support DLL3-targeted therapy as a promising treatment strategy and warrant further prospective studies to define its optimal role in the evolving SCLC treatment landscape.

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is one of the most aggressive and fatal lung malignancies, accounting for approximately 13% to 17% of all lung cancer cases [1]. It is characterized by rapid tumor growth, early dissemination, and a strong tendency toward therapeutic resistance, which collectively complicate diagnosis and management [1,2]. For patients with limited stage disease, standard treatment consists of a combined modality approach using platinum-based chemotherapy, most commonly cisplatin or carboplatin with etoposide, administered concurrently with thoracic radiotherapy. In patients who achieve complete remission, prophylactic cranial irradiation is commonly used to reduce the risk of central nervous system metastases [3,4].

In extensive stage SCLC, treatment strategies have expanded to include immunotherapy, particularly Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, in combination with conventional chemotherapy [4,5]. Despite these advances, long-term survival remains poor due to rapid development of drug resistance, frequent relapse, and substantial treatment-related toxicity [1,6]. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have transformed outcomes in several malignancies, their benefit in SCLC has been limited. While the high tumor mutational burden of SCLC suggests potential sensitivity to immunotherapy, only a subset of patients derive meaningful benefit from adding ICIs to first-line chemotherapy [7,8]. This limited efficacy has been attributed to factors such as reduced expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, impaired antigen presentation, and marked intratumoral heterogeneity [9,10]. Nevertheless, large international trials have demonstrated improved survival with the addition of PD-L1 inhibitors, including durvalumab, to chemotherapy, supporting the role of chemoimmunotherapy in SCLC [11]. Early evidence suggests that patients with more immunogenic tumors may be the primary beneficiaries of these combination approaches [1,4].

Given the limitations of current therapies, there is a clear need for novel treatment strategies in SCLC. Advances in molecular characterization and understanding of SCLC biology have enabled the development of targeted therapies designed to overcome disease progression and treatment resistance, advancing the potential for personalized therapeutic approaches [12,13]. Tarlatamab is a bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) immunotherapy that targets delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) on tumor

cells and the Cluster of Differentiation 3 (CD3) receptor on T cells, resulting in T cell activation, cytokine release, and selective cytotoxicity against DLL3-expressing cancer cells. Based on durable antitumor activity and a manageable safety profile observed in the DeLLphi-301 phase 2 trial, tarlatamab received accelerated approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration in May 2024 for patients with extensive stage SCLC who experienced disease progression after platinum-based chemotherapy [14]. This meta-analysis evaluates the efficacy and safety of tarlatamab as monotherapy and in combination with other therapies in the management of SCLC.

Methods

Study design and setting

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized evidence from clinical trials assessing the therapeutic efficacy of tarlatamab in SCLC management. Treatment approaches were categorized into four arms: Group A comprising tarlatamab monotherapy, Group B combining tarlatamab with chemotherapy, Group C combining tarlatamab with the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab, and Group D combining tarlatamab with the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab. All methodology and reporting followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines.

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception through September 2025 to identify clinical trials and observational studies evaluating tarlatamab in SCLC. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and free-text keywords using Boolean operators: (lung OR pulmonary OR bronchi* OR chest OR pleural OR alveol*) AND (tarlatamab OR DeLLphi-300 OR DLL3 OR "delta-like ligand 3" OR Imdelltra OR AMG 757) AND (cancer OR carcinoma OR malignancy OR metastasis). Truncation operators and wildcard searches were used to maximize sensitivity. No language restrictions were applied. Database searches were supplemented by hand-searching relevant journal articles and clinical trial registries to identify additional studies.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) evaluated tarlatamab as monotherapy or in combination regimens; (2) reported quantifiable clinical outcomes including response rate, overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), or time to progression; and (3) enrolled patients with extensive-stage or limited-stage who had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy or other systemic treatment. Studies evaluating tarlatamab as second-line, third-line, or subsequent-line therapy were eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were not clinical trials; (2) did not focus on tarlatamab treatment for SCLC; (3) presented overlapping or duplicate patient populations; (4) lacked adequate efficacy or safety data; (5) were published in languages other than English; (6) were preprints, abstract presentations only, or published in predatory journals.

Study selection process

Two independent researchers screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies against pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Retrieved articles that appeared potentially eligible underwent full-text review by both reviewers. Any disagreement regarding study eligibility was resolved through discussion and consensus.

Data items

Data extracted from eligible studies included: (1) study and patient characteristics (first author name, year of publication, sample size, trial phase); (2) demographic variables (median age, gender distribution, smoking status); (3) clinical baseline characteristics (ECOG performance status, metastatic sites, prior platinum-based chemotherapy, number of prior treatment lines, prior immunotherapy exposure, prior radiotherapy); (4) treatment details (tarlatamab dosing, administration frequency, median duration of therapy); (5) adverse event data (graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE], including Grade 1-5 events and serious adverse events); and (6) clinical efficacy outcomes (response rates, disease control rate, PFS, and OS).

Data analysis and synthesis

Data were extracted and organized using Microsoft Excel (2019). Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0, with results summarized as frequencies, percentages, medians, and ranges. Meta-analyses were conducted to synthesize efficacy outcomes. For binary outcomes (objective response rate and disease control rate), forest plots were generated using METAANALYSISONLINE to visualize pooled effect estimates and heterogeneity. For time-to-event outcomes (PFS and OS), Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate median survival and percentiles with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated using the Brookmeyer and Crowley method [15].

Results

Study selection

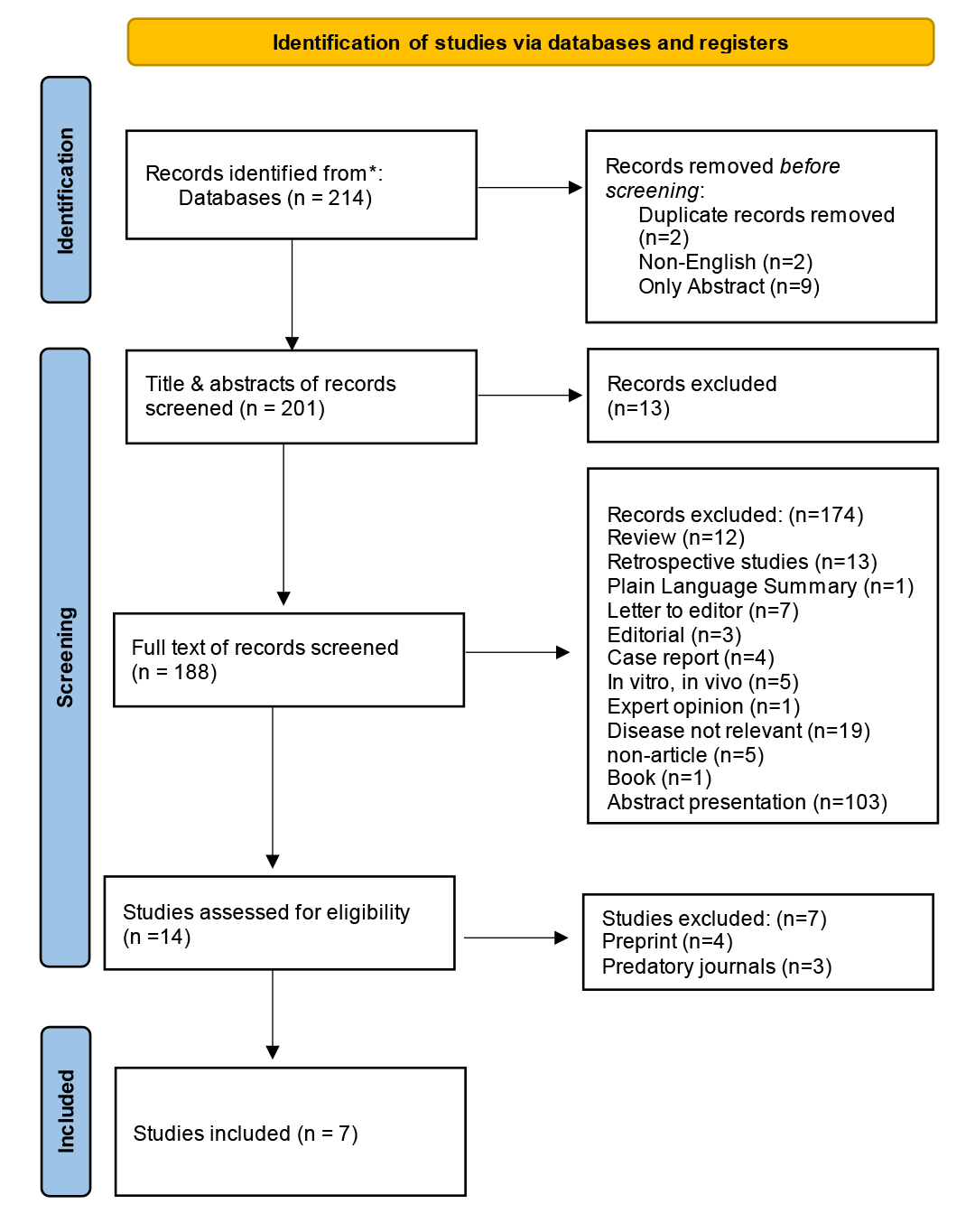

A systematic search of peer-reviewed databases initially identified 214 potentially relevant records related to tarlatamab and small cell lung cancer. Following removal of duplicates (n=2), non-English publications (n=2), and records with abstract-only availability (n=9), 201 studies underwent title and abstract screening. This process identified 188 studies for comprehensive full-text review. Application of pre-established eligibility criteria resulted in 14 studies selected for detailed evaluation. Of these, seven studies were subsequently excluded due to preprint status (n=4) and publication in predatory journals (n=3), resulting in a final cohort of 7 eligible clinical trials included in the meta-analytic synthesis [16-22]. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the complete study selection process is presented in (Figure 1). All included references reviewed to exclude non-peer-reviewed data [23].

Patient characteristics

Across the seven included clinical trials, baseline study-level characteristics indicated relatively homogeneous populations of patients with advanced small cell lung cancer. Most studies were early-phase trials evaluating tarlatamab as monotherapy or in combination regimens. Trial-level median ages ranged from 62 to 65 years, with male patients consistently representing the majority across individual studies. Brain and liver metastases were identified as the most commonly reported sites of metastatic disease across all trials (Table 1).

|

Author |

Year of publication |

Type of therapy |

Phase of clinical trial |

No. of patients |

Gender |

Median Age |

Smoking Status |

Metastasis |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Current |

Never |

Former |

N/A |

|||||||

|

Chen et al [16] |

2025 |

Tarlatamab |

1&2 |

412 |

263 |

149 |

63 |

66 |

32 |

312 |

2 |

Brain, liver |

|

Hummel H-D et al [18] |

2025 |

Tarlatamab |

2 |

100 |

72 |

28 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

100 |

Brain, liver |

|

Ahn et al [19] |

2025 |

Tarlatamab |

2 |

134 |

96 |

38 |

65 |

24 |

9 |

101 |

0 |

Brain, liver |

|

Mountzios et al [20] |

2025 |

Tarlatamab + Chemotherapy |

3 |

509 |

182 |

72 |

64 |

54 |

23 |

177 |

0 |

Brain, liver |

|

Paulson et al [21] |

2025 |

Tarlatamab + Atezolizumab, Tarlatamab + durvalumab

|

1b |

88 |

55 |

33 |

64 |

21 |

4 |

63 |

0 |

Brain, liver |

|

Dowlati et al [17] |

2024 |

Tarlatamab |

1 |

152 |

85 |

67 |

62 |

28 |

13 |

111 |

0 |

Brain, liver |

|

Paz-Ares et al [22] |

2023 |

Tarlatamab |

1 |

107 |

61 |

46 |

63 |

14 |

10 |

81 |

2 |

Brain, liver |

|

N/A: Not applicable |

||||||||||||

A total of 1,247 patients were included in the analysis. The overall median age was 63.5 years. Male patients accounted for 814 cases (65.3%), while 433 patients (34.7%) were female. Smoking status was reported for most patients, with former smokers constituting the largest subgroup (845 patients, 67.8%), followed by current smokers (207 patients, 16.6%) and never smokers (91 patients, 7.3%). Smoking history was not reported in 104 patients (8.3%) Consistent with the trial-level findings, metastatic involvement most commonly affected the brain and liver (Table 2).

|

Variables |

Number (%) |

|

Age (Year), (Median, IQR) |

63.5 (63–64) |

|

Sex -Male -Female |

-814 (65.3%) -433 (34.7%) |

|

Smoking status - Current - Never - Former - Not mentioned |

- 207 (16.6%) -91 (7.3%) -845 (67.8%) -104 (8.3%) |

|

ECOG status -ECOG status (0) -ECOG status (1) -ECOG status (2) -Not mentioned

|

Total number (1247) -280 (22.5%) -550 (44.1%) -5 (0.4%) -412 (33.0%)

|

|

Metastasis -Brain Yes No -Liver Yes No

|

Total number (1247)

-1247 (100%) -0 (0%)

-1247 (100%) -0 (0%) |

|

Previously prior therapy |

|

|

Prior platinum‑based chemotherapy/regimen - Yes - No |

Total number (1086) - 1086 (100%) - 0 (0.0) |

|

Prior PD‑1/PD‑L1 therapy - Yes - No - Not mentioned |

Total number (1502) - 963 (64.1%) - 439 (29.2%) - 100 (6.7%) |

|

Prior radiotherapy - Yes - No - Not mentioned |

Total number (1502) - 201 (13.4%) - 58 (3.9%) - 1243 (82.7%) |

|

Number of prior lines of systemic therapy - 1 line - 2 lines - 3 lines |

Total number (1400) - 728 (52.0%) - 413 (29.5%) - 259 (18.5%) |

|

Treatment group - Tarlatamab alone - Combination group |

Total number (1247) -1159 (93%) -88 (7%) |

|

Response to Tarlatamab alone and combination group - Complete response - Partial response - Stable disease - Progressive disease - Not mentioned |

Number of Patients (1247) - 16 (1.3%) - 216 (17.3%) - 207 (16.6%) - 142 (11.4%) - 666 (53.4%) |

|

Objective response rate (range %) |

21-48 |

|

Disease control rate (range %) |

51-87 |

|

Overall survival (Months) (Median, IQR) |

14.3 (13.2-19.0) |

|

Progression free survival (Months) (Median, IQR) |

4.9 (3.7-5.4) |

| IQR: Interquartile range, ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | |

Prior Therapy and Performance Status

All patients had received prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Most patients had undergone one prior line of systemic therapy (728 patients, 52.0%), followed by two prior lines in 413 patients (29.5%) and three prior lines in 259 patients (18.5%). Previous exposure to PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor therapy was reported in 963 patients (64.1%), while 439 patients (29.2%) had not received prior immunotherapy. A history of prior radiotherapy was documented in 201 patients (13.4%). Among patients with reported Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, 280 patients (22.5%) had an ECOG score of 0, 550 patients (44.1%) had a score of 1, and 5 patients (0.4%) had a score of 2. ECOG performance status was not reported for 412 patients (33.0%) (Table 2 & 3).

|

Author

|

No. of patients |

Number of prior lines of systemic therapy |

Prior platinum‑based chemotherapy/regimen |

Prior PD‑1/PD‑L1 therapy |

Prior radiotherapy |

||||||||

|

Median |

1 line |

2 lines |

3 lines |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

N/A |

||

|

Chen et al [16] |

412 |

N/A |

55 |

219 |

138 |

412 |

0 |

276 |

136 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

412 |

|

Hummel et al [18] |

100 |

2 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

|

Ahn et al [19] |

134 |

2 |

2 |

87 |

45 |

134 |

0 |

101 |

33 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

134 |

|

Mountzios et al [20] |

254 |

N/A |

509 |

0 |

0 |

509 |

0 |

360 |

149 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

509 |

|

Paulson et al [21] |

88 |

N/A |

88 |

0 |

0 |

88 |

0 |

77 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

88 |

|

Dowlati et al [17] |

152 |

2 |

44 |

62 |

44 |

152 |

0 |

96 |

56 |

0 |

116 |

36 |

0 |

|

Paz-Ares et al [22] |

107 |

2 |

30 |

45 |

32 |

103 |

0 |

53 |

54 |

0 |

85 |

22 |

0 |

Efficacy outcomes

Across the seven included studies, disease response was assessed using standardized Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) or investigator-defined criteria. In the evaluable population (n=1,247), complete response was observed in 16 patients (1.3%), partial response in 216 patients (17.3%), stable disease in 207 patients (16.6%), and progressive disease in 142 patients (11.4%). Response status was not reported or evaluable in 666 patients (53.4%), primarily due to early study termination, lack of post-baseline imaging, or classification as non-evaluable per trial protocols (Table 2).

In studies evaluating tarlatamab monotherapy, disease control rates (DCR) ranged from 51% to 82%, with objective response rates (ORR) ranging from 21% to 47%. In studies assessing combination therapy, higher response rates were observed, with DCR reaching up to 87% and ORR up to 48%. Median PFS reported across studies ranged from 3.5 to 5.6 months, while median OS ranged from 13.2 to 25.3 months. In the Asian subgroup, median OS reached 19.0 months, with a median PFS of 5.4 months (Table 4).

|

Partial response |

Complete response |

Stable disease |

Progressive Disease |

Not mentioned |

Disease control rate |

Objective response rate |

Median overall survival (months) |

Median progression free survival (months) |

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0 |

82 |

47 |

5.8 |

3.7 |

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0 |

N/A |

40 |

14.3 |

4.9 |

|

54 |

5 |

44 |

24 |

14 |

75.25 |

43.15 |

19 (Asian group) |

5.4 (Asian group) |

|

86 |

3 |

84 |

56 |

25 |

173 |

35 |

13.6 |

5.3 |

|

19 |

2 |

N/A |

N/A |

0 |

53 |

21 |

25.3 |

5.6 |

|

34 |

4 |

49 |

53 |

12 |

87 |

25 |

17.5 |

3.5 |

|

23 |

2 |

30 |

9 |

0 |

51 |

48 |

13.2 |

3.7 |

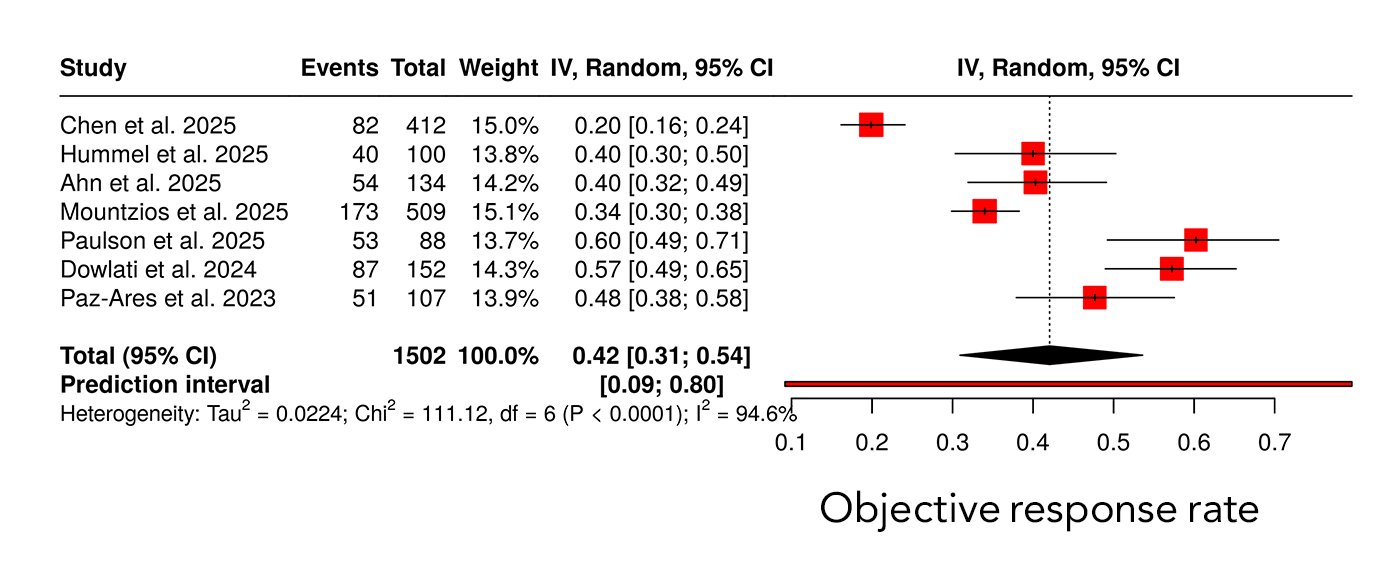

The forest plot displays individual study estimates of objective response rate with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), pooled using a random-effects model. The size of each square represents the weight of the study in the meta-analysis, while horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. The diamond represents the pooled ORR with its 95% CI. A prediction interval is shown to reflect the expected range of treatment effects in future studies. Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I² = 94.6%, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

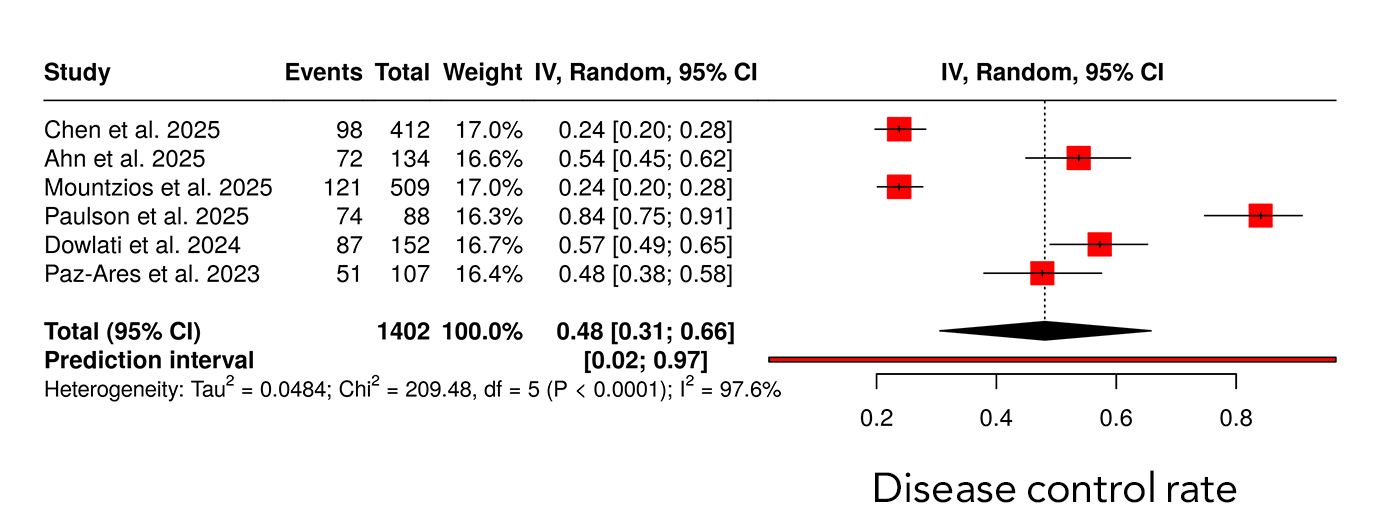

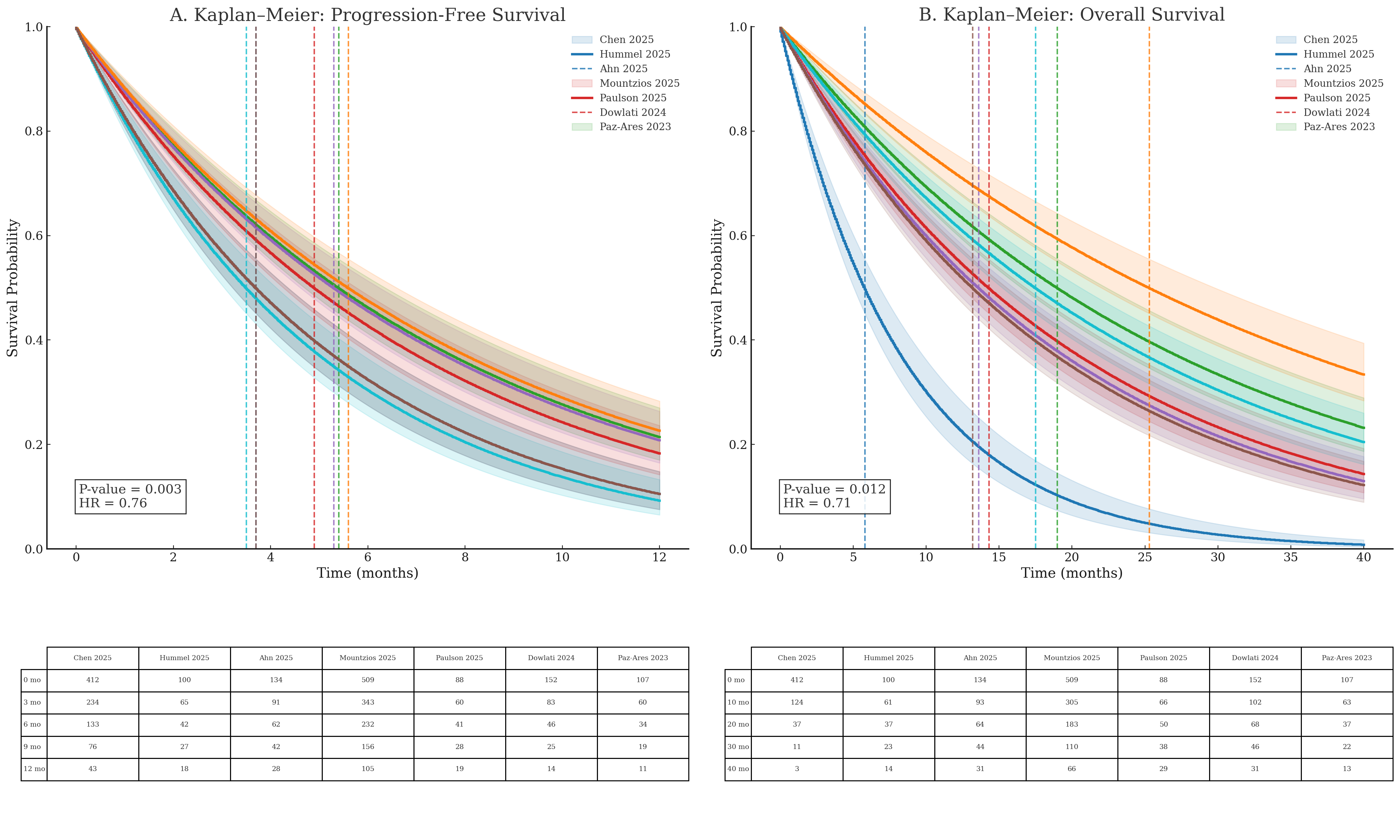

Across six studies including 1402 patients, the pooled DCR estimate was 0.48 (95% CI 0.31–0.66). Substantial heterogeneity was present, with an I² value of 97.6%. The prediction interval ranged from 0.02 to 0.97, reflecting wide variability in disease control outcomes across studies (Figure 3). Median PFS differed across studies, with reported median values ranging between approximately 3 and 6 months. The pooled Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated a hazard ratio of 0.76 with a statistically significant p-value of 0.003, as shown in the figure. Median OS across studies ranged from approximately 13 to 25 months. The pooled Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated a hazard ratio of 0.71 with a p-value of 0.012. Differences in survival trajectories among individual studies were observed over extended follow-up durations of up to 40 months. (Figure 4).

Safety outcomes

Among the reported populations, grade 2 or higher adverse events occurred in 136 patients, while grade 3 adverse events were reported in 68 patients (5.4%) and grade 4 adverse events in 17 patients (1.4%). In studies where subgroup-specific data were available, including patients from Asian populations, grade 2 or higher adverse events were reported in 39 patients, grade 3 adverse events in 24 patients, grade 4 adverse events in 7 patients, and grade 5 adverse events in 2 patients. Serious adverse events were reported in 129 patients in studies that documented this outcome. For a substantial proportion of patients, adverse event severity and grading were not reported and were therefore categorized as not available in the safety dataset (Table 5).

|

Adverse Event Rates |

|||||

|

Grade 1 |

Grade ≥ 2 |

Grade ≥ 3 |

Grade ≥ 4 |

Grade ≥ 5 |

Serious adverse events |

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

N/A |

39 (Asian group) * |

24 (Asian group) * |

7 (Asian group) * |

NA |

2 (Asian group) * |

|

N/A |

N/A |

136 |

N/A |

N/A |

129 |

|

8 |

29 |

38 |

13 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

N/A |

119 |

68 |

17 |

N/A |

65 |

|

N/A |

N/A |

33 |

N/A |

1 |

55 |

|

* Were available only for the Asian subgroup, as corresponding safety data for the overall study population were not reported. |

|||||

Discussion

Small cell lung cancer remains one of the most aggressive solid malignancies, characterized by rapid tumor proliferation, early metastatic dissemination, and persistently poor survival outcomes. Despite advances in chemo-immunotherapy, the disease is largely incurable in advanced stages, with most patients relapsing within six months following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Outcomes after platinum failure are particularly poor, as standard second-line therapies such as topotecan and lurbinectedin demonstrate ORR below 20% and median OS rarely exceeding 10 months [22,24]. These limited clinical benefits underscore a major unmet therapeutic need in relapsed SCLC. Consequently, there has been growing interest in identifying biologically driven targets capable of delivering more durable responses with acceptable safety profiles [20,24]. Among emerging targets, DLL3 has gained attention due to its high and selective expression on SCLC tumor cells and minimal presence in normal tissues [1,20,25]. This tumor-restricted expression pattern provides a strong biological rationale for DLL3-directed therapeutic strategies in relapsed SCLC.

Previous prospective and real-world studies have consistently demonstrated poor outcomes for patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer following platinum failure. Rudin et al. and Paz-Ares et al. reported objective response rates generally below 20% with standard second-line therapies such as topotecan and lurbinectedin, with median overall survival rarely exceeding 10 months [22,24]. These findings highlight a substantial unmet therapeutic need in this setting [24]. In contrast, the present meta-analysis demonstrated enhanced clinical activity with tarlatamab-based therapy, yielding a pooled objective response rate of 42% and disease control rates ranging from 51% to 87%, depending on the treatment regimen. Notably, both monotherapy and combination approaches achieved tumor response rates that exceeded those historically reported with conventional chemotherapy. Although cross-study comparisons should be interpreted with caution, the magnitude of improvement observed relative to prior literature supports the therapeutic potential of DLL3-targeted therapy with tarlatamab in relapsed SCLC and underscores the need for further prospective validation.

Metastatic burden at baseline was substantial and consistent with advanced small cell lung cancer. Previous studies have shown that the brain and liver are among the most frequent sites of metastasis in SCLC, with brain involvement reported in approximately 40–70% of patients over the disease course[20,22]. In line with these reports, brain and liver metastases were the most commonly observed metastatic sites across the included trials in the present meta-analysis. The presence of extensive metastatic disease reflects a real-world advanced SCLC population and reinforces the external validity and generalizability of the observed treatment outcomes.

Performance status is a well-established prognostic factor in small cell lung cancer; however, its influence on treatment outcomes remains a subject of debate, particularly in the context of clinical trial selection. Rudin et al. and Paz-Ares et al. have shown that patients with impaired ECOG performance status experience lower response rates, shorter progression-free survival, and reduced overall survival, yet these patients are frequently underrepresented in prospective trials [20,22]. In the present meta-analysis, most evaluable patients had favorable baseline performance status, with 22.5% classified as ECOG 0 and 44.1% as ECOG 1, indicating that approximately two-thirds of patients entered treatment with preserved functional capacity. Only a small proportion of patients had an ECOG score of 2 (0.4%), while ECOG status was not reported in one-third of cases. This imbalance highlights an ongoing controversy regarding the generalizability of trial-based efficacy estimates and suggests that treatment benefits may be overestimated when extrapolated to patients with poorer functional reserve.

Historically, patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer have experienced poor outcomes following platinum failure. Rudin et al., Paz-Ares et al., Dowlati et al., and Sands et al. have reported that standard second-line therapies such as topotecan and lurbinectedin typically achieve objective response rates below 20%, with median overall survival rarely exceeding 10 months [14,17,22,24]. Against this background, the present meta-analysis demonstrates that tarlatamab provides clinically meaningful antitumor activity in a heavily pretreated SCLC population. Among 1,247 evaluable patients, complete and partial responses were observed in 1.3% and 17.3% of patients, respectively, resulting in a pooled objective response rate of 42%. Furthermore, disease control was achieved in nearly half of treated patients, with rates reaching up to 87% in combination regimens, substantially exceeding historical chemotherapy benchmarks.

Survival outcomes further support the clinical relevance of these findings. Median progression-free survival ranged from 3.5 to 5.6 months, while median overall survival extended from 13.2 to 25.3 months across individual studies. Rudin et al., Paz-Ares et al., Dowlati et al., and Sands et al. have consistently reported that historical second-line therapies such as topotecan, lurbinectedin, and amrubicin yield median overall survival of approximately 5.8–10 months, underscoring the limited durability of benefit in this setting [14,17,22,24]. Against this benchmark, the observed 2–3-fold improvement in median overall survival with tarlatamab suggests a clinically meaningful survival advantage in relapsed SCLC. Pooled time-to-event analyses further demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the risk of disease progression and death, with hazard ratios of 0.76 for progression-free survival and 0.71 for overall survival. Notably, subgroup analyses indicated that Asian patients achieved a median overall survival of approximately 19 months, consistent with individual trial reports and supporting the reproducibility of benefit across populations. Remarkably, survival outcomes achieved with tarlatamab in the relapsed setting approached or in some studies exceeded those reported with first-line chemo-immunotherapy regimens, such as CASPIAN and KEYNOTE-604, where median overall survival ranges from 12.3 to 13.0 months [17,22,24]. Although cross-trial comparisons should be interpreted with caution, achieving comparable survival outcomes in later treatment lines represents a particularly striking observation, given the well-established pattern of diminishing benefit with successive therapies in SCLC.

The observed efficacy of tarlatamab is biologically plausible and aligns with the established role of DLL3 in small cell lung cancer pathogenesis. Ding et al. and Zhang et al. have demonstrated that DLL3 is highly expressed in neuroendocrine SCLC and contributes to tumor proliferation and maintenance through dysregulated Notch signaling [1,25]. By simultaneously engaging CD3-positive T cells and DLL3-expressing tumor cells, tarlatamab induces potent T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity independent of major histocompatibility complex class I–restricted antigen presentation, thereby circumventing key immune evasion mechanisms characteristic of SCLC, as highlighted by Rudin et al. and Paz-Ares et al. [22,24]. This mechanism of action clearly distinguishes tarlatamab from immune checkpoint inhibitors and may explain its robust antitumor activity in a disease that has historically demonstrated limited responsiveness to immunotherapy.

Importantly, tarlatamab appears to offer superior efficacy and tolerability compared with earlier DLL3-targeted approaches such as rovalpituzumab tesirine. Rudin et al. and Paz-Ares et al. reported that although rovalpituzumab tesirine demonstrated modest response rates, it failed to improve survival and was associated with substantial toxicity and high treatment discontinuation rates in phase III trials [22,24]. In contrast, tarlatamab exploits endogenous immune effector mechanisms without the delivery of a cytotoxic payload, resulting in an improved therapeutic index and a more favorable safety profile, as supported by findings from Rudin et al., Paz-Ares et al., and Ding et al. [1,22,25].

Across the included studies, tarlatamab was generally well tolerated. Severe adverse events were infrequent, with grade 3 and grade 4 toxicities reported in 5.4% and 1.4% of patients, respectively. The most commonly observed treatment-related adverse events were consistent with the expected profile of T-cell engager therapies, particularly cytokine release syndrome, which was predominantly low-grade and rapidly reversible with standard supportive measures. Paz-Ares et al. and Sands et al. reported that neurotoxicity was uncommon and typically mild, with grade 3–4 events occurring in only a small minority of patients [14,22]. Compared with conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, these findings suggest a more favorable balance between efficacy and tolerability. This observation was further reinforced by the phase III DeLLphi-304 trial, in which Rudin et al. demonstrated significantly lower rates of severe adverse events and treatment discontinuation with tarlatamab compared with physician’s-choice chemotherapy [22].

Indirect treatment comparisons using real-world data provide additional support for these findings. After adjustment for baseline prognostic factors, Wang et al. reported that tarlatamab was associated with significantly improved overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective response rate compared with real-world comparator therapies [2], suggesting that the observed clinical benefit extends beyond the controlled setting of clinical trials and may be generalizable to broader patient populations. Substantial heterogeneity was observed across pooled analyses, reflecting differences in study design, treatment regimens, and patient characteristics. In the context of relapsed SCLC, such variability is expected and reflects real-world clinical complexity. Importantly, the persistence of tarlatamab activity across heterogeneous settings supports the robustness of its antitumor effect. Patients with lower baseline tumor burden, preserved performance status, and absence of liver metastases appeared more likely to achieve sustained disease control, suggesting that patient selection and earlier intervention may optimize outcomes. These observations should be interpreted cautiously and provide hypothesis-generating insights that warrant further prospective evaluation.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The meta-analysis included a limited number of studies, many of which were early-phase trials, and substantial heterogeneity was observed across efficacy outcomes. Response assessment was incomplete in a proportion of patients, particularly in dose-escalation studies, and safety reporting was inconsistent across trials. Additionally, the absence of individual patient-level data precluded detailed subgroup and biomarker analyses. These limitations underscore the need for further randomized trials and biomarker-driven studies to refine patient selection and confirm the long-term clinical role of tarlatamab in SCLC.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed the clinical relevance of DLL3-targeted therapy as a promising treatment strategy for advanced small cell lung cancer. The findings indicate that tarlatamab offers meaningful antitumor activity in a setting characterized by limited therapeutic options following standard treatments. Importantly, the favorable balance between efficacy and tolerability supports the continued clinical development of this approach. Further well-designed prospective studies are needed to clarify the optimal positioning of tarlatamab within the evolving treatment landscape of SCLC.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Not applicable.

Funding: The present study received no financial support.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: KKM, SMA and KAN were responsible for data collection and analysis, and final approval of the manuscript. BAA and RML were major contributors to the conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for related studies. MQM, ZKH, SAH, MAR, SKM, BTM, and SAB were involved in the literature review, the design of the study, and the critical revision of the manuscript. BAA was involved in the literature review, the writing of the manuscript, and design of the study and data interpretation. BAA and RML confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Use of AI: ChatGPT version 5.2 (OpenAI) was used solely for language editing, paraphrasing, and improvement of clarity and grammar in this manuscript. The artificial intelligence tool did not contribute to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the generation of scientific content. All outputs produced with the assistance of ChatGPT were carefully reviewed, verified, and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and originality of the entire manuscript.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ding J, Yeong C. Advances in DLL3-targeted therapies for small cell lung cancer: challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Frontiers in Oncology. 2024; 14:1504139. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1504139

- Wang Y, Zou S, Zhao Z, Liu P, Ke C, Xu S. New insights into small‐cell lung cancer development and therapy. Cell biology international. 2020;44(8):1564-76. doi:10.1002/cbin.11359

- Dingemans AM, Früh M, Ardizzoni A, Besse B, Faivre-Finn C, Hendriks LE, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology. 2021;32(7):839-53. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.03.207

- Ganti AK, Loo BW, Bassetti M, Blakely C, Chiang A, D'Amico TA, et al. Small cell lung cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021;19(12):1441-64. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2021.0058

- Tariq S, Kim SY, Monteiro de Oliveira Novaes J, Cheng H. Update 2021: management of small cell lung cancer. Lung. 2021;199(6):579-87. doi:10.1007/s00408-021-00486-y

- Petty WJ, Paz-Ares L. Emerging strategies for the treatment of small cell lung cancer: a review. JAMA oncology. 2023;9(3):419-29. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.5631

- Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO open. 2022;7(2):100408. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100408

- Gay CM, Stewart CA, Park EM, Diao L, Groves SM, Heeke S, et al. Patterns of transcription factor programs and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer cell. 2021;39(3):346-60. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.014

- Stewart CA, Gay CM, Xi Y, Sivajothi S, Sivakamasundari V, Fujimoto J, et al. Single-cell analyses reveal increased intratumoral heterogeneity after the onset of therapy resistance in small-cell lung cancer. Nature cancer. 2020;1(4):423-36. doi:10.1038/s43018-019-0020-z

- Tian Y, Zhai X, Han A, Zhu H, Yu J. Potential immune escape mechanisms underlying the distinct clinical outcome of immune checkpoint blockades in small cell lung cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2019;12(1):67. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0753-2

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum–etoposide versus platinum–etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1929-39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6

- Hendriks LE, Menis J, Reck M. Prospects of targeted and immune therapies in SCLC. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2019;19(2):151-67. doi:10.1080/14737140.2019.1559057

- Esposito G, Palumbo G, Carillio G, Manzo A, Montanino A, Sforza V, Costanzo R, Sandomenico C, La Manna C, Martucci N, La Rocca A. Immunotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Cancers. 2020;12(9):2522. doi:10.3390/cancers12092522

- Sands JM, Champiat S, Hummel HD, Paulson KG, Borghaei H, Alvarez JB, et al. Practical management of adverse events in patients receiving tarlatamab, a delta‐like ligand 3–targeted bispecific T‐cell engager immunotherapy, for previously treated small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2025;131(3):e35738. doi:10.1002/cncr.35738

- Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982:29-41. doi:10.2307/2530286

- Chen PW, Minocha M, Kong S, Jiang T, Anderson ES, Parkes A, et al. Tarlatamab Exposure–Efficacy and Exposure–Safety Relationships to Inform Dose Selection in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2025;31(22):4688-97. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-25-2134

- Dowlati A, Hummel HD, Champiat S, Olmedo ME, Boyer M, He K, et al. Sustained clinical benefit and intracranial activity of tarlatamab in previously treated small cell lung cancer: DeLLphi-300 trial update. Journal of clinical oncology. 2024;42(29):3392-9. doi:10.1200/JCO.24.00553

- Hummel HD, Ahn MJ, Blackhall F, Reck M, Akamatsu H, Ramalingam SS, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes for Patients with Previously Treated Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Tarlatamab: Results from the DeLLphi-301 Phase 2 Trial. Advances in Therapy. 2025:1-5. doi:10.1007/s12325-025-03136-4

- Ahn MJ, Cho BC, Ohashi K, Izumi H, Lee JS, Han JY, et al. Asian Subgroup Analysis of Patients in the Phase 2 DeLLphi-301 Study of Tarlatamab for Previously Treated Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncology and Therapy. 2025;13(4):1041-54. doi:10.1007/s40487-025-00372-0

- Mountzios G, Sun L, Cho BC, Demirci U, Baka S, Gümüş M, et al. Tarlatamab in small-cell lung cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2502099

- Paulson KG, Lau SC, Ahn MJ, Moskovitz M, Pogorzelski M, Häfliger S, et al. Safety and activity of tarlatamab in combination with a PD-L1 inhibitor as first-line maintenance therapy after chemo-immunotherapy in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (DeLLphi-303): a multicentre, non-randomised, phase 1b study. The Lancet Oncology. 2025;26(10):1300-11. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(25)00480-2

- Paz-Ares L, Champiat S, Lai WV, Izumi H, Govindan R, Boyer M, et al. Tarlatamab, a first-in-class DLL3-targeted bispecific T-cell engager, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase I study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023 ;41(16):2893-903. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02823

- Hussein Kakamad F, Abdallla BA, Mohammed SH. Shifting from'Predatory Journals' to'Non-Recommended Journals': A Proposal to Reduce Conflicts and Promote Ethical Discourse. In18th EASE General Assembly and Conference 2025. ScienceOpen. doi: N/A

- Rudin CM, Reck M, Johnson ML, Blackhall F, Hann CL, Yang JC, et al. Emerging therapies targeting the delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) in small cell lung cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2023;16(1):66. doi:10.1186/s13045-023-01464-y

- Zhang H, Yang Y, Li X, Yuan X, Chu Q. Targeting the Notch signaling pathway and the Notch ligand, DLL3, in small cell lung cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023;159:114248. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114248

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.