Suffering of Patients with Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS); The First Qualitative study in TOS

Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS) is hindered by symptom overlap with cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or psychosomatic disorders. This challenge is further compounded by often normal imaging and electrodiagnostic findings, resulting in prolonged diagnostic suffering encompassing emotional, financial, and social burdens.

Objectives

This first qualitative study explores narratives from 25 diagnosed women initially prescribed physiotherapy: (1) identify key themes related to diagnostic challenges; (2) examine the psychological and emotional impact of diagnostic delay; and (3) propose a patient-centered diagnostic framework.

Methods

Qualitative descriptive design using semi-structured interviews (20-30 minutes) with purposive sampling from a TOS clinic (inclusion: confirmed nTOS, >1-year symptoms, no prior surgery; Data saturation was achieved after 22 interviews). Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis generated 1,247 inductive codes, which were organized into four themes and twelve subthemes. NVivo software was used for data management. Member checking was conducted, and reporting followed COREQ guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained, and participant anonymity was preserved through pseudonyms.

Results

Four overarching themes emerged: (1) Fragmented Diagnostic Odyssey, characterized by multiple referrals (mean six clinicians per patient) and substantial out-of-pocket costs (USD 1,000–1,500); (2) Cascade of Misdiagnoses, including somatic mimics, invasive investigations, and prolonged incorrect treatment; (3) Social and Familial Invalidation, involving medical dismissal and pressure toward psychiatric explanations; and (4) Profound Emotional Suffering, with isolation and hopelessness identified in 84% of transcripts. A conceptual model was developed to illustrate the cumulative diagnostic journey.

Conclusion

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is associated with multilayered diagnostic and social invalidation consistent with the stigma of invisible illness. Improving outcomes requires enhanced clinician awareness of nTOS-specific red flags, validation of patient narratives, and multidisciplinary diagnostic pathways to reduce delays, prevent iatrogenic harm, and alleviate psychological distress.

Introduction

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS) is characterized by compression of the brachial plexus as it traverses the thoracic outlet, causing upper extremity pain, numbness, paresthesia, and variable degrees of weakness. The condition predominantly affects young women, often triggered by repetitive overhead activities, postural strain, or antecedent trauma. Despite its clinical relevance, nTOS remains one of the most diagnostically challenging peripheral nerve compression syndromes due to its heterogeneous and fluctuating presentation [1,2].

Clinical recognition is often delayed, as symptoms overlap substantially with more prevalent conditions such as cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, peripheral neuropathies, and functional or psychosomatic disorders. The absence of definitive radiological or electrodiagnostic findings in many patients further compounds diagnostic uncertainty, contributing to prolonged diagnostic latency that may span several years [1,2]. Consequently, patients frequently undergo multiple inconclusive investigations and consultations before receiving an accurate diagnosis [1,2].

Beyond physical morbidity, individuals with nTOS experience a form of diagnostic suffering, encompassing emotional distress, financial strain, social disruption, and erosion of trust in healthcare systems. Recurrent symptom invalidation and misattribution may intensify anxiety, frustration, and feelings of marginalization. This experience closely parallels Bury’s concept of biographical disruption in chronic illness, whereby delayed or contested diagnoses fracture personal identity, future planning, and the patient–clinician relationship [3,4].

The present study seeks to illuminate these underexplored qualitative dimensions through in-depth narratives from 25 diagnosed women, all of whom were initially prescribed physiotherapy as first-line management. The study objectives are threefold: (1) to identify recurring themes related to diagnostic challenges and healthcare encounters; (2) to explore the psychological and emotional impact of prolonged diagnostic trajectories; and (3) to propose a patient-centered diagnostic framework that integrates biomedical assessment with experiential and psychosocial dimensions.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative descriptive study design with interpretive orientation was employed using semi-structured conversations to explore participants lived experiences of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, this approach was selected to capture rich, first-person accounts while remaining close to participants’ language and meanings. The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [5].

Participants and sampling

Purposive sampling recruited 25 female patients from a TOS specialty clinic. Inclusion: confirmed nTOS diagnosis, physiotherapy as initial treatment, symptom duration >1 year. Exclusion: surgical intervention prior to study. Saturation achieved after 22 interviews, with 3 additional for confirmation. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a confirmed diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, (2) initiation of physiotherapy as first-line management, and (3) symptom duration exceeding one year. Patients who had undergone surgical intervention prior to study enrollment were excluded. Data saturation was reached after 22 interviews, with three additional interviews conducted to confirm thematic completeness and stability.

Data collection

One-on-one conversations (20–30 minutes) in a private clinic room to ensure confidentiality and participant comfort A semi-structured interview guide was used to explore diagnostic trajectories, experiences of misdiagnosis, emotional and psychological impact, and social responses to symptoms. Sample prompts included: “Can you walk me through your journey to receiving a diagnosis?” and “How did family members or healthcare providers respond to your symptoms?” (Table 1). All interview were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim, yielding approximately 450 pages of textual data.

|

Interview Guide Domains |

Sample Questions |

|

Diagnostic Journey |

"What tests did you undergo? How many specialists?" |

|

Misdiagnoses & Treatments |

"What alternative diagnoses were suggested?" |

|

Emotional/Social Impact |

"How did this affect your relationships or self-view?" |

|

Validation & Recovery |

"What changed after nTOS diagnosis?" |

Data analysis

Braun and Clarke's (2006) reflexive thematic analysis in six phases (6):

- Familiarization: Repeated, immersive reading of transcripts to gain an overall understanding of the data.

- Coding: Inductive line-by-line coding was performed, generating 1,247 initial codes.

- Theme Generation: Collating into 4 main themes, 12 subthemes.

- Review: Preliminary themes were reviewed and refined through member checking with ten participants.

- Definition: Themes were clearly defined, refined, and supported by illustrative patient quotations.

- Reporting: Final themes were synthesized and presented using verbatim extracts to preserve participants’ voices.

NVivo 14 used for management. Methodological rigor and trustworthiness were enhanced through maintenance of an audit trail, thick description, reflexive journaling, and transparency regarding researcher positioning; the researchers declared no personal or clinical conflicts of interest related to thoracic outlet syndrome.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for human research. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. Pseudonyms were assigned to protect confidentiality. Participants were provided with debriefing following the conversations and offered referral resources for psychological or clinical support if needed.

Results

Analysis of interviews with 25 participants (coded P1–P25) yielded four overarching themes, each comprising related subthemes supported by illustrative verbatim quotations.

Theme 1: Fragmented Diagnostic Odyssey

Participants described a prolonged and exhausting diagnostic trajectory characterized by repeated referrals and inconclusive investigations across multiple medical specialties. On average, participants reported consulting approximately six physicians prior to receiving a diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome.

Subtheme 1.1: Endless Investigations

"I have done hundreds of investigations; each doctor tells me a different diagnosis." (P7) "I cannot count how many doctors I visited; no one told me you have nTOS." (P14) These accounts highlight a cycle of uncertainty in which repeated testing failed to yield diagnostic closure.

Subtheme 1.2: Financial and Time Toll

The diagnostic delay was accompanied by substantial financial and temporal burden. Participants reported out-of-pocket expenditures ranging from approximately USD 1,000 to 1,500, in addition to lost workdays and prolonged functional impairment.

Theme 2: Cascade of Misdiagnoses

Symptom overlap with other neurological, musculoskeletal, and systemic conditions frequently resulted in misdiagnosis and inappropriate interventions.

Subtheme 2.1: Somatic Mimics: Several participants underwent unnecessary or unrelated treatments based on incorrect attribution of symptoms:

"I extracted three teeth; they told me that I have a tooth problem." (P3) "I did physiotherapy for several months; the doctor told me that you have cervical radiculopathy." (P19).

Subtheme 2.2: Life-Threatening Errors

- In some cases, misinterpretation of symptoms led to invasive and anxiety-provoking investigations:

"I did CT and conventional angiography; they suspected cardiac problems." (P11). - These experiences intensified fear and reinforced perceptions of bodily vulnerability.

- Subtheme 2.3: Chronic Mislabeling: Long-term misdiagnosis resulted in prolonged exposure to ineffective treatments:

- "For the last five years, I have been taking medication for migraine; I did not know I have nTOS." (P22)

- Participants described frustration at years of symptom management without etiological understanding.

Theme 3: Social and Familial Invalidation

Beyond medical encounters, participants reported invalidation within social and familial contexts, often leading to isolation and stigmatization.

Subtheme 3.1: Medical Gaslighting

Several participants perceived dismissal of their symptoms as psychological or fabricated:

"Even I faced social problems; they told me you have no disease, you are a psychopath all those investigations are normal, so you have no disease." (P5).

Such experiences contributed to erosion of trust in healthcare providers.

Subtheme 3.2: Familial Pressure

Family members, influenced by medical uncertainty, frequently encouraged psychiatric consultations:

- "Several times I visited psychiatrist; my family forced me to visit them. I knew that I have a somatic problem." (P17).

- This dynamic amplified patients’ sense of not being believed.

Theme 4: Profound Emotional Suffering

- The cumulative effect of diagnostic delay, mislabeling, and invalidation resulted in marked emotional distress.

- Subtheme 4.1: Isolation and Despair

- Participants expressed persistent feelings of loneliness, hopelessness, and emotional exhaustion:

- "I have been very upset as no one understands my suffering." (P9).

- Themes of hopelessness and emotional despair were identified in 84% of transcripts, underscoring the psychological toll of prolonged diagnostic uncertainty.

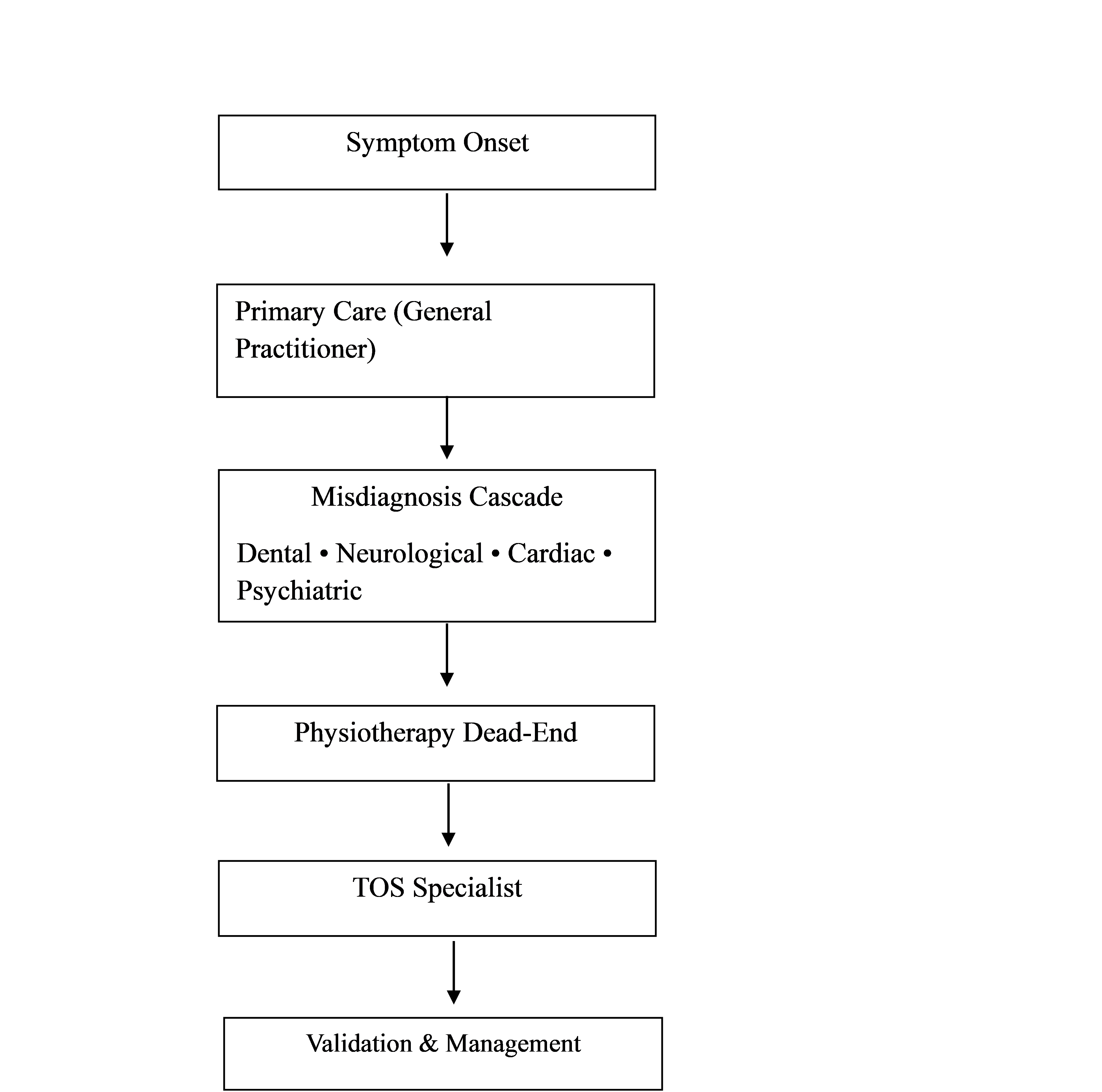

To facilitate interpretation, a conceptual model was developed to visually represent the cumulative and distressing diagnostic journey experienced by participants (Figure 1), integrating clinical, emotional, and social dimensions of the illness trajectory.

Discussion

Neurogenic TOS acts as a "diagnostic chameleon," with symptoms mimicking many common conditions. It presents a significant diagnostic challenge because its symptoms overlap extensively with a wide range of neurological, musculoskeletal, and systemic conditions, making differential diagnosis complex. Cervical spine pathology, particularly cervical radiculopathy due to disc herniation, spondylosis, or foraminal stenosis, is one of the most important differentials, as it can produce neck pain radiating to the upper limb, paresthesia, weakness, and sensory disturbances that mimic nTOS. Peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes such as carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve), cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve), and radial tunnel syndrome may coexist with or masquerade as nTOS [6,7].

Brachial plexopathies due to trauma, tumors, radiation injury, or inflammatory processes must also be considered, particularly when symptoms are progressive, asymmetric, or associated with objective neurological deficits. In addition, Shoulder pathologies – such as rotator cuff disease, adhesive capsulitis, and impingement syndrome, commonly present with pain exacerbated by arm elevation and are frequently misinterpreted as thoracic outlet pathology. Myofascial pain syndromes, especially involving the scalene, trapezius, or pectoralis minor muscles, can closely mimic nTOS, contributing to pain, heaviness, and paresthesia without clear structural compression. Rheumatological conditions such as fibromyalgia, inflammatory arthritis, or connective tissue diseases may produce widespread pain, fatigue, and sensory symptoms [6,7].

Given this broad differential, the diagnosis of nTOS remains largely clinical, dependent on meticulous history-taking, thorough physical examination, exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and a multidisciplinary approach to avoid misdiagnosis and prolonged patient suffering [8,9].

Misdiagnosis in nTOS is not benign. In the present cohort, incorrect diagnostic attribution resulted in iatrogenic harm, including unnecessary dental extractions and invasive investigations such as conventional angiography. These findings underscore how diagnostic uncertainty can escalate into physical harm, psychological distress, and avoidable healthcare expenditures an issue increasingly recognized in patient safety literature.

Beyond biomedical consequences, participants described profound social invalidation in chronic illness contexts embodies the stigma of "invisible illnesses," where the absence of visible markers or abnormal test results often leads healthcare providers and society to attribute symptoms to psychosomatic causes, thereby undermining patient credibility and autonomy. This medical invalidation involves dismissal or minimization of patient reports, particularly among women, or young adults (typically nTOS patients), fostering a cycle of doubt that erodes patient agency. Medical invalidation often manifests as minimization or dismissal of patient-reported symptoms, particularly when diagnostic tests are normal. Rather than resolving uncertainty, normal results may paradoxically intensify clinician skepticism, shifting explanatory frameworks from physiological to psychological domains. This process can lead to diagnostic overshadowing, patient self-doubt, and erosion of trust in healthcare relationships [10,11]. The emotional suffering described by participants closely parallels Joseph Dumit's concept of "illnesses you have to fight to get treated," drawn from analyses of multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS), where patients face systemic barriers in uncertain, emergent illnesses, with bureaucratic and institutional reliance on established biomarkers denying legitimacy and forcing collective advocacy to counter exclusions. This fight manifests in newsgroup archives and patient activism, revealing rhetorical tactics by institutions that exploit scientific open-endedness to reject emerging facts, perpetuating costly struggles for recognition. Invalidation extends beyond clinics to social services and workplaces, with high discounting reported in insurance interactions, hindering return-to-work efforts and amplifying shame, while gender and minority intersections intensify stigma through diagnostic overshadowing leading to loneliness, helplessness, and mental health crises [10-13].

Clinical implications for managing nTOS emphasize rigorous training on key red flags to facilitate early detection and intervention, including positional symptoms such as pain, paresthesia, or weakness exacerbated by overhead arm positions, overhead activities, or specific postures like carrying heavy loads, alongside provocative tests like the elevated arm stress test (EAST). Other critical red flags encompass supraclavicular tenderness, thenar atrophy signaling chronic median nerve involvement, positive Adson or Wright maneuvers eliciting radial pulse diminution or symptom reproduction, and vascular signs like hand pallor or Raynaud-like phenomena during maneuvers. Multidisciplinary TOS clinics, integrating vascular surgeons, neurologists, physiatrists, physical therapists, and pain specialists, may cut diagnostic and treatment delays significantly potentially by streamlining evaluations via coordinated imaging (MRI neurography, dynamic venography), standardized protocols, and surgical referrals addressing the typical 1-2 year lag from symptom onset to definitive care that perpetuates deconditioning, psychological distress, and suboptimal outcomes in this anatomically complex syndrome involving scalene hypertrophy, cervical ribs, or fibromuscular bands. Evidence supports such clinics reducing misdiagnoses (e.g., labeling nTOS as "psychosomatic" or shoulder pathology), improving surgical success rates to 80-90% via first-rib resection or scalenectomy when conservative measures like physical therapy, nerve blocks, or Botox fail, and enhancing patient-centered metrics including return-to-work timelines and quality-of-life scores through holistic management that tackles myofascial triggers, posture correction, and psychosocial support. Implementing these in high-volume centers could standardize care, lower healthcare costs from repeated consultations [14-18].

Future directions in nTOS research prioritize mixed-methods studies incorporating male patients to address current gender imbalances, as existing literature predominantly features female cohorts due to higher reported prevalence and referral biases, potentially overlooking male-specific biomechanics like broader clavicular spans, occupational overhead strain in trades, or delayed presentations from stoicism, thereby enabling qualitative insights into lived experiences alongside quantitative metrics on symptom trajectories, diagnostic timelines, and treatment responses to refine inclusive diagnostic algorithms and prognostic models. Such studies could employ patient diaries, focus groups, and wearable sensor data to capture nuanced positional triggers absent in traditional cohorts, while longitudinal tracking via standardized scales (e.g., DASH for disability, SF-36 for quality-of-life) elucidates sex-disaggregated outcomes post-scalenectomy or therapy, informing tailored rehabilitation protocols that mitigate male underdiagnosis risks like conflation with rotator cuff pathology. Concurrently, intervention trials targeting clinician education represent a critical frontier, testing structured curricula to enhance recognition of red flags like supraclavicular tenderness or thenar wasting, countering few years diagnostic odyssey driven by misattribution to psychogenic causes. Randomized controlled trials could randomize primary care providers or neurologists to intervention arms versus controls, measuring endpoints like referral accuracy to multidisciplinary TOS clinics, reduction in unnecessary MRIs, and patient-reported delays, with embedded knowledge translation via pre/post assessments and fidelity checks to ensure scalability across community and academic settings [14,16-18].

This study has several limitations. The female-only sample limits generalizability to male populations. Retrospective accounts are subject to recall bias, and recruitment from a single specialty clinic may introduce selection bias. Nonetheless, the depth and consistency of narratives provide valuable insight into the lived experience of diagnostic delay in nTOS.

Conclusion

Delayed or missed diagnosis of nTOS inflicts multilayered suffering, extending beyond physical symptoms to encompass emotional distress, social invalidation, and erosion of trust in healthcare systems. The findings underscore the urgent need for a shift toward syndrome-aware, patient-centered, and empathetic diagnostic approaches that recognize both the clinical complexity of nTOS and the lived experiences of affected individuals. Early validation of patient narratives combined with rigorous clinical assessment and multidisciplinary collaboration has the potential to shorten diagnostic pathways, reduce iatrogenic harm, and transform prolonged diagnostic odysseys into meaningful trajectories of recognition, relief, and recovery.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Patient consent (participation and publication): Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their legal guardians for participation in this study and for the publication of any accompanying images, clinical information, and other data included in the manuscript.

Funding: The present study received no financial support.

Acknowledgements: None to be declared.

Authors' contributions: SHM and BAA were major contributors to the conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for related studies. FHK, YNA and AKG were involved in the literature review and the writing of the manuscript. SKA, NSS, LJM, ASH, CSO, AHA, OMH, LAS, AAM, and AHH were involved in the literature review, the design of the study, the critical revision of the manuscript, and the preparation of the table and figure. FHK and BAA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Use of AI: ChatGPT Plus (OpenAI, version 4) was used solely to assist with language editing and to improve the clarity of the manuscript. All content was carefully reviewed and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and originality of the entire work.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Fahmi H. Kakamad, Berun A. Abdalla, Saywan K. Asaad, Hawkar A. Nasralla, Abdullah K. Ghafour, Hiwa S. Namiq, et al. Provocative Tests in Diagnosis of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Judi Clin. J. 2025;1(1):46-50. doi:10.70955/JCJ.2025.5

- Jones, M.R., Prabhakar, A., Viswanath, O. et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Pain Ther 8, 5–18 (2019). doi:10.1007/s40122-019-0124-2

- Dengler, N. F., Ferraresi, S., Rochkind, S., Denisova, N., Garozzo, D., Heinen, C., et al . Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part I: Systematic Review of the Literature and Consensus on Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Classification of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome by the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies' Section of Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Neurosurgery. 2022; 90(6), 653. doi:10.1227/neu.0000000000001908

- Bury, M. (1982) ‘Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption’ Sociology of Health and Illness 4(2): 167–182. doi:N/A

- Allison Tong, Peter Sainsbury, Jonathan Craig. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19 (6): 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3(2), 77–101 (2006). doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(3):601-4. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.050

- Fahmi H. Kakamad, Saywan K. Asaad, Abdullah K. Ghafour, Nsren S. Sabr, Hiwa S. Namiq, Lawen J. Mustafa, et al. Differential Diagnosis of Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Review. Barw Medical Journal. 2025.25;3(2). doi:10.58742/bmj.v3i2.161

- Dengler NF, Pedro MT, Kretschmer T, Heinen C, Rosahl SK, Antoniadis G. Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome—Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119(43):735-742. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0296

- Dumit, J. Illnesses you have to fight to get: Facts as forces in uncertain, emergent illnesses. Social Science & Medicine. 2006; 62(3): 577–590

- Kundrat, A. L., & Nussbaum, J. F. ). The Impact of Invisible Illness on Identity and Contextual Age Across the Life Span. Health Communication. 2003; 15(3), 331–347. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1503_5

- Sebring JCH, Kelly C, McPhail D, Woodgate RL. Medical invalidation in the clinical encounter: a qualitative study of the health care experiences of young women and nonbinary people living with chronic illnesses. CMAJ Open. 2023;11(5):E915-E921. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20220212

- Shim, J.-M. (2022). Patient Agency: Manifestations of Individual Agency Among People with Health Problems. Sage Open. 2022; 12(1). doi:10.1177/21582440221085010

- Jones MR, Prabhakar A, Viswanath O, Urits I, Green JB, Kendrick JB, et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Pain Ther. 2019;8(1):5-18. doi:10.1007/s40122-019-0124-2

- Kakamad FH, Ghafour AK, Nasralla HA, Asaad SK, Sabr NS, Tahir SH, et al. Rare etiologies of thoracic outlet syndrome: A systematic review. World Academy of Sciences Journal. 2025;7(5):95. 2025;7:95. doi:10.3892/wasj.2025.383

- Li N, Dierks G, Vervaeke HE, Jumonville A, Kaye AD, Myrcik D, et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):962. doi:10.3390/jcm10050962

- Karl A. Illig, Dean Donahue, Audra Duncan, Julie Freischlag, Hugh Gelabert, Kaj Johansen, et al. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2016;64(3):23-35. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.039

- Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a review. Neurologist. 2008;14(6):365-73. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e318176b98d

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.